Throughout history, advertising has followed the consumer through the invention and rise of new mediums, from the print world to the online world.

But the world of online advertising has brought with it a number of issues that have caused companies, governments, and consumers to take a proactive approach to limiting the amount of user data that can be collected.

In this chapter, we’ll look at one of the biggest topics in programmatic advertising; user privacy.

The Rise of Consumer Data Collection and Privacy Concerns

In the early days of online advertising, ad targeting was limited to the context of the page and information passed to ad servers and ad networks in the user agent string (passed in a HTTP header) by web browsers, such as:

- The language set on the user’s computer.

- The URL of the page where the ad will be displayed.

- The browser type and version.

- The user’s operating system.

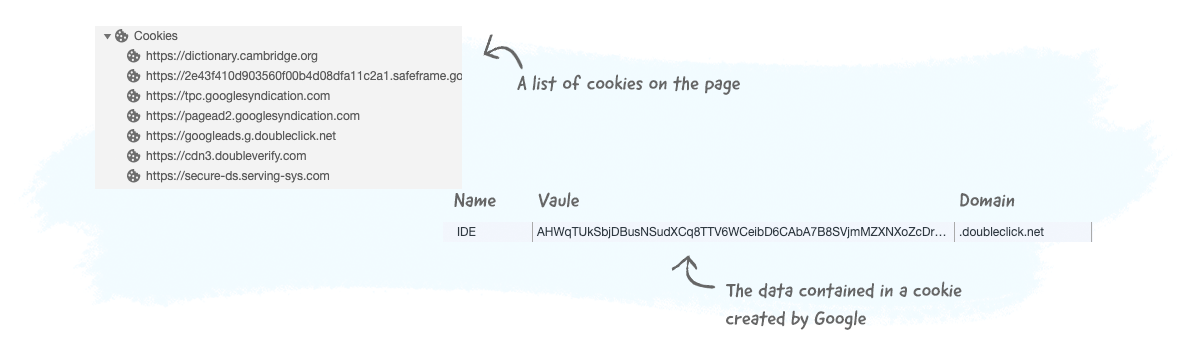

When RTB emerged in the late 2000’s, AdTech companies started ramping up the use of third-party cookies to identify users across different websites and display ads to them based on their interests and behavior.

Nowadays, user data can be collected in several ways and combined with data collected from different sources to improve ad targeting, measurement, attribution and conduct frequency capping.

The amount of user data collected by AdTech and data companies has increased significantly over the years, which has given rise to concerns about how companies are collecting this data and what they are doing with it.

To learn about how users are identified, the types of data that AdTech companies collect, and how data is collected, read chapters 10. User Identification and 11. Data Management Platforms (DMPs) and Data Usage.

The user privacy topic in AdTech is made up of privacy laws (e.g. the GDPR and CCPA) and privacy settings and technical limitations (e.g. ad blockers and web browser settings).

Privacy and Data Protection Laws Around The World

More and more users are becoming concerned about the collection, use, and distribution of their online data. Many are also worried that their privacy is being invaded and exploited by online advertising companies.

In this section, we’ll look at the various privacy and data laws in the US and Europe.

The European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), or Regulation (EU) 2016/679 as it’s known in official contexts, is a regulation spearheaded by the three legislative European Union institutions: the European Parliament, European Commission, and Council of the European Union.

It replaced the Data Protection Directive (Directive 95/46/EC) when it came into force on May 25, 2018.

The GDPR aims to protect the data and privacy of citizens and residents of the European Union member states (highlighted in light blue). Even though Norway, Iceland, and Liechtenstein (highlighted in dark blue) are not EU member states, they are European Economic Area (EEA) members and are also included in the GDPR.

Key Terms of the GDPR

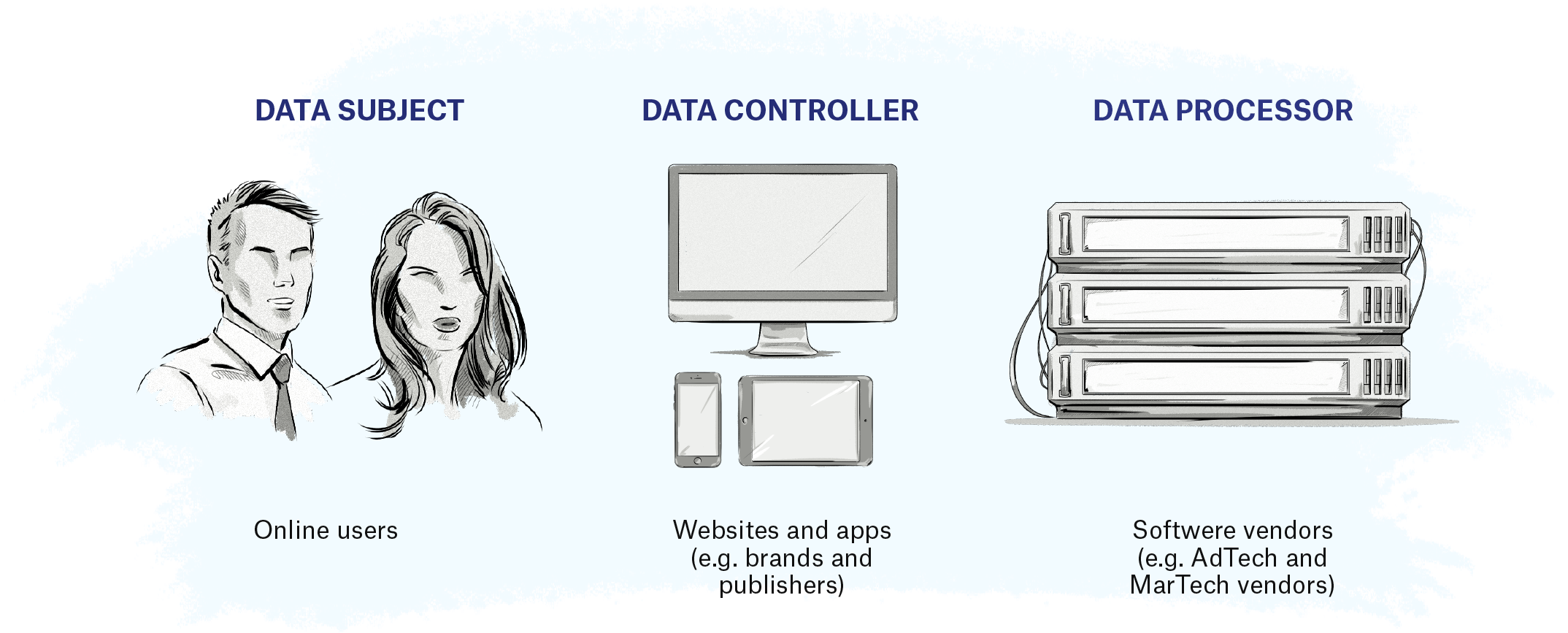

Below are three key terms that relate to online advertising and marketing: data subject, data controller, and data processor.

Data Subject

The GDPR defines a data subject as a natural person whose personal data is processed by a controller or processor.

In the context of digital advertising, a data subject is an EU or EEA citizen or resident whose data can be collected by AdTech companies.

Data Controller

A data controller is any person or company that collects data about EU citizens and residents.

Examples include publishers, ecommerce stores, individual bloggers, brands, and companies that collect data about users either directly or indirectly via another company.

Data Processor

A data processor is any person or company that provides services or technology and collects data on behalf of data controllers.

Examples include AdTech and MarTech vendors.

Personal, Pseudonymous, and Anonymous Data

Another key term in the GDPR is personal data.

In simple terms, if a piece of information, either separately or combined with other pieces of data, can be used to identify a person, then it’s classed as personal data.

‘Personal data’ means any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person (‘data subject’); an identifiable natural person is one who can be identified, directly or indirectly, in particular by reference to an identifier such as a name, an identification number, location data, an online identifier, or to one or more factors specific to the physical, physiological, genetic, mental, economic, cultural, or social identity of that natural person.

Article 4 (1)

GDPR

Identity in this sense doesn’t just refer to knowing a person’s name, it also refers to identification.

This means if a user visits your website or sees one of your ads, they are considered identifiable if you can later recognize them, e.g. by identifying and recognizing them via their cookie ID or other identifier, if they return to your website or see another one of your ads.

The same principle applies to singling out an individual based on several data points, such as their postal code, gender, and age. In this case, even though you don’t know the person’s name or have an identifier, e.g. a user ID in a cookie saved in their browser, you could still potentially identify them.

In the past, AdTech vendors and most MarTech vendors have based their privacy policies on the fact that they are not collecting or dealing with personal data because online identifiers, such as cookie IDs, IP addresses, device advertising IDs, and device fingerprints were not considered examples of personal data.

However, under the GDPR, any piece of data or information that can in some way identify a person is classed as personal data.

Apart from personal data, the GDPR also refers to two other types of data: pseudonymous and anonymous.

Pseudonymous data refers to data that’s been changed into a non-identifiable format, rendering it unable to identify a person without the use of additional data, such as the hashing function or encryption keys.

‘Pseudonymization’ means the processing of personal data in such a manner that the personal data can no longer be attributed to a specific data subject without the use of additional information, provided that such additional information is kept separately and is subject to technical and organizational measures to ensure that the personal data are not attributed to an identified or identifiable natural person.

Article 4 (5)

GDPR

Anonymous data means that it can’t be used to identify a person, which, for this reason, offers little value to online advertising and marketing companies as they are in the business of identifying people and targeting them with ads and marketing messages.

Due to its inability to identify a person, anonymous data is not subject to the rules of the GDPR, meaning if a company collects anonymous data, they don’t have to obtain user consent.

…The principles of data protection should therefore not apply to anonymous information, namely information which does not relate to an identified or identifiable natural person or to personal data rendered anonymous in such a manner that the data subject is not or no longer identifiable. This Regulation does not, therefore, concern the processing of such anonymous information, including for statistical or research purposes.

Recital 26

GDPR

A Comparison of the Three Types of Data

Below is a comparison table that provides examples of personal, anonymous, and pseudonymous data.

| Type of Information Collected | Personal Data | Pseudonymous Data | Anonymous Data | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Device information |

AEBE52E7-03EE-455A-B3C4-E57283966239

Device advertising identifier (e.g. Apple’s IDFA – Identifier for Advertising) |

e69a1078552e13f2734 Device advertising identifier Using a one-way hash function to convert the data into a non-identifiable format. The device can be re-identified by applying the same hash function to the original value and comparing it to the pseudonymous hash. |

Apple iPhone 7 Device brand and model |

|

| Email address |

john.smith@company.com Email address |

1bc5edb4799fd8eec67 Email address Similar to the advertising one-way hash function. |

company.com Domain of the email address |

|

| Web activity (e.g. pageviews) |

213.86.17.58 https://clearcode.cc/ A list of page URLs visited on a website along with an IP address of the visitor. |

8d61a1f53fdc1b74. https://clearcode.cc/ A list of page URLs visited on a website along with a randomly generated unique identifier that has been set in the visitor’s browser cookie. |

500+ pageviews http://clearcode.cc/about/ An aggregated number of times a given page was viewed https://clearcode.cc/ A list of the page URLs visited on a website without containing cookie IDs, IP addresses, or any other personally identifiable information. |

|

| Address and DOB |

742 Evergreen Terrace Address November 24, 1971 Date of birth |

1971 The year of birth and a postal code. By using an external database, a data subject can be re-identified, hence the data cannot be considered anonymous. |

89** Suppressing certain parts of the data, e.g. removing the last two digits of a postcode. 45-54 Age range instead of the exact age. |

The column on the left contains different types of user information, then shows how the data would look under the different categories of data: personal data, anonymous data, and pseudonymous data.

From the table above, it appears that anonymous data is the least likely to expose the identity of a data subject.

While that is true in most cases, it’s important to keep in mind that the anonymized data could still be linked to an individual if enough pieces of data are combined together.

For example, having a single data point, like an age range of 40–50, out of a sample size of 1,000 couldn’t be linked to an individual, but when you add in other anonymized data sets (e.g. postcodes and the year of birth) and combine with other sets of data (e.g. public records or data), it can easily become personal data and could be used to identify an individual.

Did you know?

There have been a number of situations of anonymized data becoming re-identifiable, with one example being Netflix’s 2006 contest in which the company put up a $1 million prize for the person or team who could significantly improve their recommendation algorithm. As part of the content, Netflix released 10 million movie rankings by 500,000 customers, which included the following information:

- A unique subscriber ID

- Movie title

- Year of release

- The date on which the subscriber rated the movie

Even though personally identifiable information, such as customer name, was replaced with a unique ID, two researchers at the University of Texas at Austin, Arvind Narayanan and Vitaly Shmatikov, were able to de-anonymize some of the data and identify certain users by comparing user ratings and the date on which they rated the movies with information from the site Internet Movie Database (IMDB).

A Side Note About Sensitive Data

The GDPR also includes another type of data class: sensitive data.

Examples of sensitive data include religious or philosophical beliefs, racial or ethnic origin, political opinions, trade-union membership, and data concerning health, sex life, and sexual orientation.

Sensitive data is typically not collected by advertisers or marketers as it requires stronger grounds for processing and is subject to additional protections, meaning the payoff just isn’t viable.

Advertisers and marketers wishing to collect, store, and use sensitive data should be aware that they will need to obtain explicit consent from the data subject.

What Does This Mean for AdTech From a Technical Perspective?

The definition of personal data is somewhat unchanged from the definition given in the Directive; however, it broadened the scope of the data-protection law.

One example of the change in scope is that the GDPR now considers online identifiers and location data as personal data.

As most online advertisers, marketers, and publishers collect and use online identifiers, such as those mentioned above, as well as location data, they will now have to take additional steps to ensure they are compliant with the GDPR’s rules regarding the collection, storage, and usage of personal data.

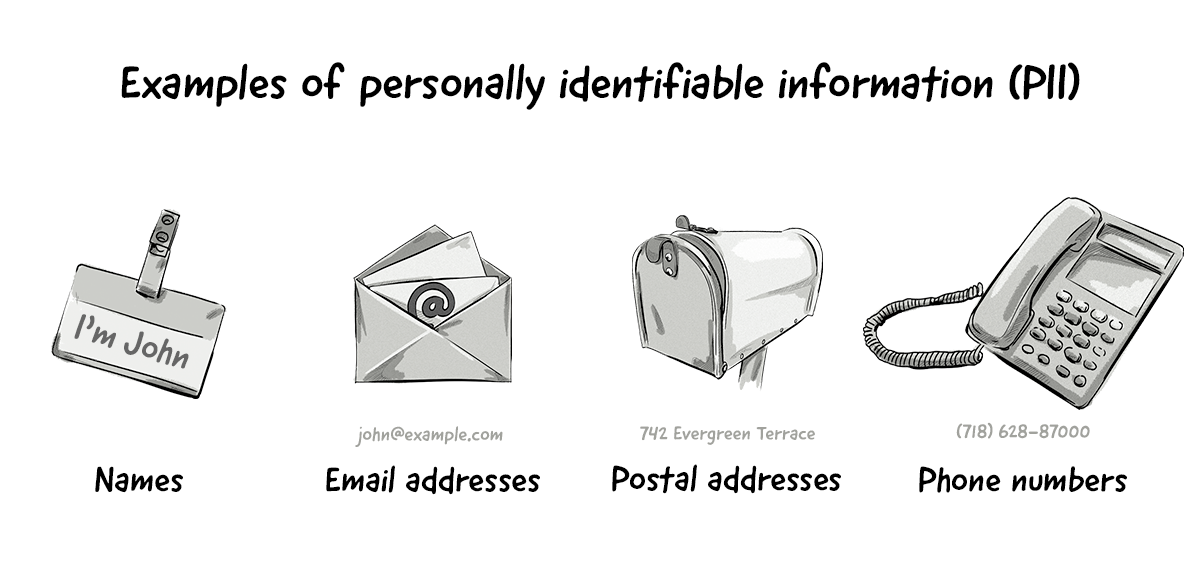

Examples of personal data include:

- Names

- Email, home, and work addresses

- Phone numbers

- Cookie IDs (visitor identifiers stored in cookies)

- IP addresses

- Device IDs

- Device fingerprints

The GDPR states that companies collecting personal data should implement measures to ensure the data is protected at all times, for instance, via encryption and pseudonymization.

Although most companies already do this with obvious examples of personal data, such as emails, phone numbers, and IP addresses, they now have to apply this to all types of data they collect.

While these measures will help online advertising and marketing companies mitigate risks associated with data security, encrypted and pseudonymized data are still classed as personal data, meaning companies still have to obtain user consent and carry out various data-protection measures if they wish to collect and use the information.

The main challenges advertising and marketing companies face with personal data are collecting it in the first place (i.e. obtaining consent), ensuring its security, and creating a chain of responsibility with their partners when they exchange data with them.

The European Union’s ePrivacy Directive

The ePrivacy directive is a piece of EU legislation that also aims to protect the data and privacy of EU and EEA citizens and residents, but with a focus on respecting their private lives when using electronic communications.

Within the online advertising and marketing industries, the current ePrivacy directive is often conversationally referred to as the cookie law because it regulates the usage of cookies, among other identifiers.

However, it relates to the protection of privacy in the electronic-communications sector as a whole, not just the usage of cookies for online advertising and marketing.

One of the most prominent consequences of the ePrivacy directive (officially known as the Privacy and Electronic Communications Directive, 2002/58/EC) is the cookie-consent notices — also known as cookie bars — like the one below from bbc.co.uk:

Currently, ePrivacy is a directive, but is in the process of being transformed into a regulation, which will also repeal the current directive.

Once adopted, ePrivacy will regulate the processes of placing, accessing, and using identification technologies on users’ devices based on the broadened definition of personal data as recognized by the GDPR (e.g. cookies, device advertising IDs, and IP addresses).

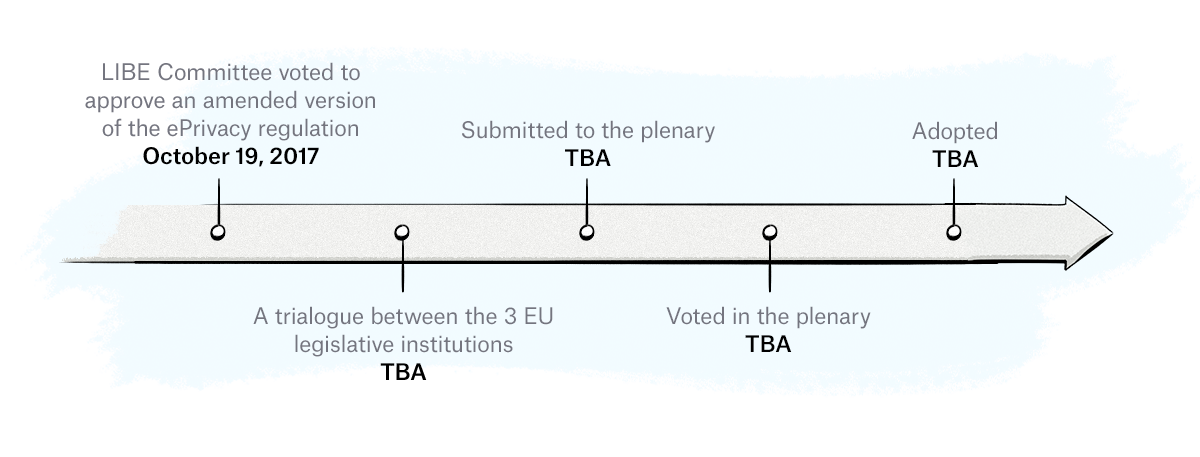

It is not known when the ePrivacy regulation will come into force as the proposal is set to be negotiated between the three EU legislative institutions (see below).

Given that it is still in progress, the final version of the ePrivacy regulation may still affect how AdTech platforms interact with online identifiers based on the GDPR itself and the current state of ePrivacy.

What’s the difference between GDPR and ePrivacy?

Both the GDPR and ePrivacy are based on Articles of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, a document containing the rights and freedoms protected in the EU.

The GDPR is based on Article 8 and relates to the protection of personal data, whereas ePrivacy is based on Article 7 and relates to respect for private life.

In simple terms, the GDPR is focused on data protection, and ePrivacy is focused on the right to respect a data subject’s private and family life, home, and communications.

Also, ePrivacy is lex specialis of the GDPR, meaning that when the two regulations cover the same situation, ePrivacy will override the GDPR.

The Current State of ePrivacy

In December 2016, a draft of the proposed ePrivacy regulation was leaked, with the first official draft formally released by the European Commission in January 2017.

On October 19, 2017, the European Parliament’s Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice, and Home Affairs (aka LIBE Committee) voted to approve an amended version of the ePrivacy regulation. This amended version was then approved by members of the European Parliament during a plenary session (a meeting of the whole Parliament).

Another draft was released in March 2019, with subsequent proposals released in March 2019 and November 2019.

The drafts have been met with some strong opposition from various advertising and marketing organizations, including the Interactive Advertising Bureau Europe (IAB Europe) and Digital Europe — whose members include Google, Apple, Microsoft, and IBM — with their main concerns centered around the lawfulness of data processing based on the notion of legitimate interest.

Once the draft has been finalized, the next stage involves trilogue negotiations between representatives of the European Parliament, the Council of the European Union, and the European Commission. Once the proposal is finalized and approved by way of voting, it will be adopted and enforced.

California Consumer Privacy Act of 2018

The California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) is a law passed by the California State Legislature on June 28, 2018 and came into effect on January 1, 2020. Enforcement of the act began on July 1, 2020.

The goal of the CCPA is to make it easier for Californian citizens and residents to know the types of personal information businesses collect about them, and give them the right not to agree to the sale of their personal data to other parties

The CCPA provides Californian citizens and residents with the following rights:

- Right to know all the data a business collects about them.

- Right to say NO to the sale of their information.

- Right to DELETE their data.

- Right to be informed of what categories of data will be collected about them prior to its collection, and to be informed of any changes to this collection.

- Mandated opt-in before sale of children’s information (under the age of 16).

- Right to know the categories of third parties with whom their data is shared.

- Right to know the categories of sources of information from whom their data was acquired.

- Right to know the business or commercial purpose of collecting their information.

- Enforcement by the Attorney General of the State of California.

- Private right of action when companies breach their data.

What are the Non-Compliance Fines?

Under the CCPA, fines are enforced by the California Attorney General and can reach up to $7,500 per every violation (in the case of intentional violations). Non-intentional violations remain subject to the $2,500 maximum fine.

Also, the CCPA allows affected consumers to take individual or class-action lawsuits against offending businesses, which should be a more serious financial concern for potential violators. Damages range between $100 and $750 – or more, if actual damages are proven.

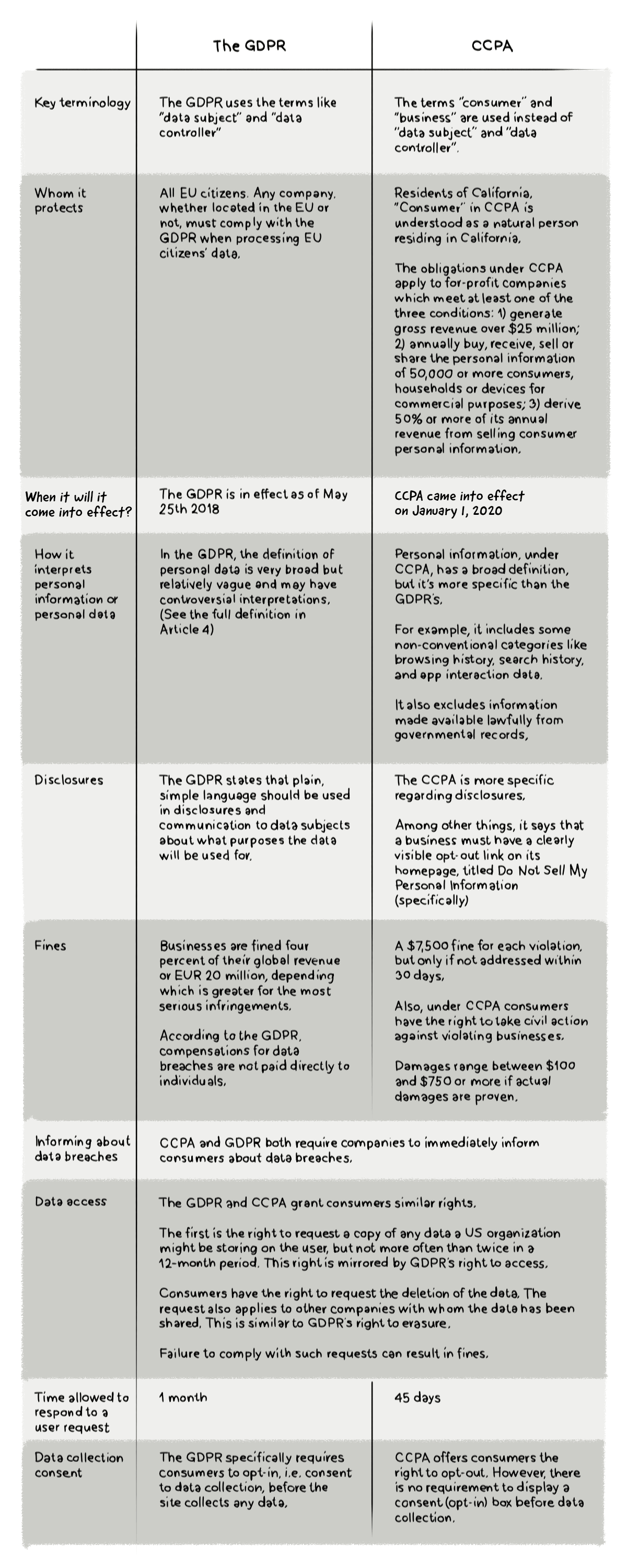

CCPA vs GDPR: What Are the Similarities and Differences?

Let’s have a look at the most important similarities and differences:

The Definition of Personally Identifiable Information (PII) and Personal Data

Personally Identifiable Information (PII) is a term regularly used in AdTech, but it extends well past this industry.

In fact, PII is often referenced by US government agencies, such as the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST).

NIST provides the following definition of PII:

PII is any information about an individual maintained by an agency, including (1) any information that can be used to distinguish or trace an individual‘s identity, such as name, social security number, date and place of birth, mother‘s maiden name, or biometric records; and (2) any other information that is linked or linkable to an individual, such as medical, educational, financial, and employment information.

A very similar definition is provided by US Government’s Office of Management and Budget:

The term “personally identifiable information” refers to information which can be used to distinguish or trace an individual’s identity, such as their name, social security number, biometric records, etc. alone, or when combined with other personal or identifying information which is linked or linkable to a specific individual, such as date and place of birth, mother’s maiden name, etc.

What Pieces of Information are Considered PII?

PII can be divided into two categories: linked information and linkable information.

Linked information is any piece of personal information that can be used to identify an individual and includes, but is not limited to, the following:

- Full name

- Home address

- Email address

- Social security number

- Passport number

- Driver’s license number

- Credit card numbers

- Date of birth

- Telephone number

- Internet protocol (IP) address

Linkable information, on the other hand, is information that on its own may not be able to identify a person, but when combined with another piece of information could identify, trace, or locate a person.

Here are some examples of linkable information:

- First or last name (if common)

- Country, state, city, postcode

- Gender

- Race

- Non-specific age (e.g. 30-40 instead of 30)

- Job position and workplace

Non-PII

There’s a lot of grey area around whether identifiers like cookie IDs and device IDs are examples of PII or non-PII.

While the definition of PII doesn’t include a specific reference to cookie IDs or device IDs, the Guide to Protecting the Confidentiality of Personally Identifiable Information (PII) from the NIST suggests that they are classed as PII (emphasis ours):

Asset information, such as Internet Protocol (IP) or Media Access Control (MAC) address or other host-specific persistent static identifier that consistently links to a particular person or small, well-defined group of people.

However, many AdTech companies, advertisers, and publishers class cookie IDs and device IDs as non-PII.

One could argue that cookie IDs and device IDs can be deleted or reset and therefore aren’t persistent forever, but the same could be said for other types of PII such as home addresses, email addresses, and phone numbers that can change more than once during a person’s life.

The Definition of Personal Data

As we mentioned above in the section about the GDPR, personal data is a term used in the European Union to define a piece of information that can be used to identify a person.

Examples of personal data include:

- Names

- Email, home, and work addresses

- Phone numbers

- Cookie IDs (visitor identifiers stored in cookies)

- IP addresses

- Device IDs

- Device fingerprints

What’s the Difference Between PII and Personal Data?

The difference between PII and personal data can be explained by the following:

Personally Identifiable Information (PII) is a term used mainly within the USA.

Personal Data is a term used in the EU’s GDPR. Even though it is considered to be the European equivalent of PII, it doesn’t completely correspond to the PII definition popular in the US.

Browser Settings

Although popular web browsers have long provided some level of privacy protection in the form of DoNotTrack, few have implemented technical settings to strengthen user privacy when browsing the web.

But this has all changed over the past few years with the most popular web browsers by market share — Google Chrome, Mozilla’s Firefox, and Apple’s Safari — making gradual changes to how their web browsers handle cookies and other storage and tracking methods (e.g. device fingerprinting) to strengthen privacy for users.

Let’s now take a look at how web browsers have strengthened user privacy and the impact these changes have had on digital advertising.

Apple’s Safari

Apple’s first real initiative to strengthen user privacy came in 2015 when they allowed iOS users to install content blockers (a form of ad blocking).

These content blockers can be downloaded from the App Store and used to prevent certain content (e.g. ads) and tracking cookies from loading in the Safari web browser on Apple smartphones and tablets.

Then, in September 2017, Apple stepped up their privacy game by introducing Intelligent Tracking Prevention (ITP) with the release of Safari 11 and iOS 11.

ITP is a feature of Webkit, an open-source web-browser engine that powers Apple’s Safari web browser, that aims to further protect users’ online privacy by changing the way Safari handles user identification methods, such as first- and third-party cookies.

The way ITP works is by classifying domains that are capable of tracking users across different domains via its Machine Learning Classifier.

Since its initial release, ITP has strengthened user privacy by limiting the lifespan of cookies and other data storage methods with every new update.

Here’s an overview of the main restrictions ITP places on cookies and other browser storage methods as per ITP 2.3:

- Third-party cookies are blocked by default.

- First-party cookies created by JavaScript’s Document.cookie API are set to expire in 7 days.

- First-party cookies created by JavaScript’s Document.cookie API, classified as a tracking domain by the Machine Learning Classifier, and created via a link containing a query string or id fragment (known as link decoration) are set to expire in 24 hours.

- Data stored in local storage is set to expire in 7 days.

- All cookies created by a third-party CNAME-cloaked HTTP response will be set to expire in 7 days.

- In 2021, ITP will add a new feature that will hide a user’s IP address from trackers.

How Does Intelligent Tracking Prevention Impact Digital Advertising?

The main problem companies in the digital advertising industry face when it comes to ITP is that it’s harder to identify users across different websites.

The ability to identify a person across different websites is important for the following reasons:

- Monetization for publishers: The more a publisher knows about a visitor, the more ad revenue it will receive from advertisers, as we explain in the next point.

- Revenue for advertisers: Advertisers want to reach a specific audience, and if a member of that audience accesses a publisher’s site, they’ll likely submit a high bid in hopes their ad will be shown to them.

- Relevance for users: Although most people are uneasy with ads that follow them around the web, many users will click on or interact with ads if they are relevant to them; for example, an ad for a upcoming Metallica concert at CenturyLink Field would be of great interest to a heavy-metal fan living in Seattle.

- Attribution: One of the most overlooked areas of this whole identity problem is attribution. It’s estimated that global digital ad spend in 2019 will reach $316 billion, and without an accurate way to identify users as they move across the Internet and devices, it will be hard to track performance and know where to assign budgets.

In response to the limitations imposed on them by ITP, many AdTech companies have created workarounds, but these have either been eliminated or restricted with new releases of ITP.

Privacy Changes in iCloud+

Apple will introduce new privacy features that will be available to iCloud+ subscribers, which will be the paid iCloud subscriptions. The below changes won’t be applied to the free iCloud subscriptions.

Private Relay

Private Relay encrypts the traffic between the Safari browser and the website a user is visiting. Nobody, including Apple or the network provider, can read the information being passed.

Here is Apple’s explanation on how its Private Relay works:

All the user’s requests are then sent through two separate internet relays. The first assigns the user an anonymous IP address that maps to their region but not their actual location. The second decrypts the web address they want to visit and forwards them to their destination. This separation of information protects the user’s privacy because no single entity can identify both who a user is and which sites they visit.

Mail Privacy Protection

This feature will prevent email senders from using invisible pixels to identify when a user opens an email. It will also mask a user’s IP address so that it can’t be used to determine their location or linked with other online activity.

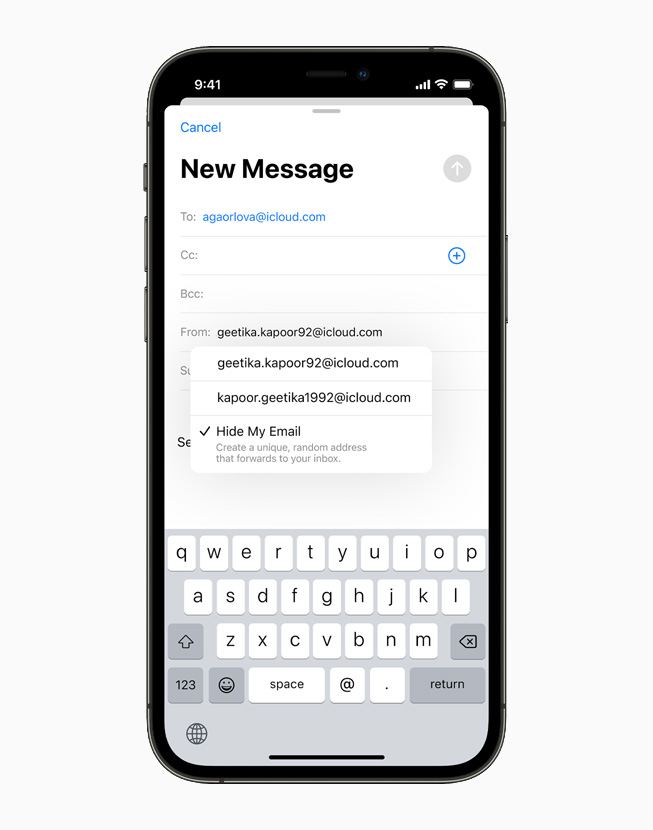

Hide My Mail

The Hide My Mail feature will allow users to use a unique and randomly generated email address instead of using their actual email address.

The newly generated email address will forward to the user’s personal email address and users can create and delete as many “hidden” email addresses as they like.

The Impact of These Changes on Programmatic Advertising and AdTech

While these changes will increase user privacy, their impact on programmatic advertising and AdTech won’t be as severe as some of the other privacy changes Apple has introduced.

Mail Privacy Protection will likely disrupt how email automation and MarTech tools work as they won’t be able to report on open rates.

The Hide My Mail feature will throw a spanner in the works for ID graphs and ID solutions built around email addresses.

As these changes will only apply to iCloud+ subscriptions, not every Apple user will be covered by these changes.

According to a group of Barclays analysts, Apple has around 850 million iCloud users, with about 170 million of those users on paid subscriptions, which accounts for 20% of all iCloud subscribers.

So around 170 million Apple users will see these new privacy changes come into effect when iCloud+ is released. The number of iCloud+ subscriptions makes up only 12% of Apple’s 1.4 billion active users.

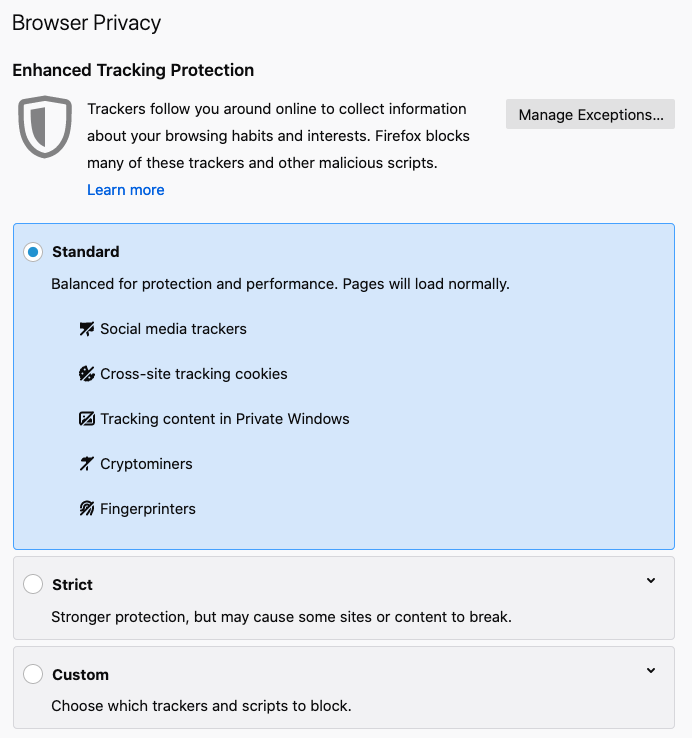

Mozilla’s Firefox

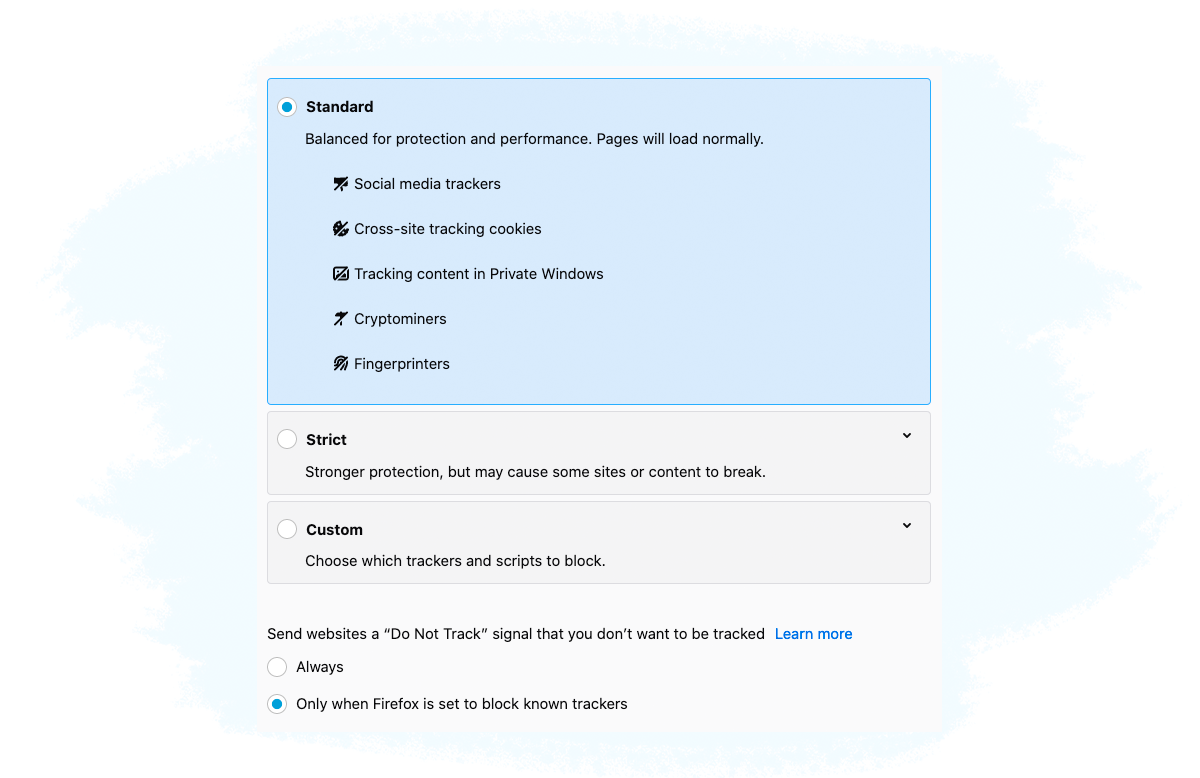

Firefox has also stepped up their privacy game by introducing Enhanced Tracking Protection (ETP) in June 2019 that blocked known trackers when browsing in private mode.

Then in September of the same year, Firefox released an update of ETP that blocks known third-party trackers as the default option for all Firefox users.

Apart from blocking known trackers, Firefox also blocks social media trackers, device fingerprints, and cryptominers.

Google Chrome

Despite the fact that Google has a lot of skin in the digital advertising game with a large chunk of Google’s revenue coming from ads and their own ad products, it has also made changes to improve the user experience and strengthen user privacy over the past few years.

Chrome’s Better Ads Standards

On February 15, 2018, Chrome released a built-in filter that blocks ads that don’t comply with the Better Ads Standards proposed by the Coalition for Better Ads formed by leading associations and companies (including Google and Facebook). The coalition’s goal is to improve consumers’ experiences with online ads.

The filter does not get rid of ads completely (like a regular ad blocker), but protects the user from the most disruptive ads.

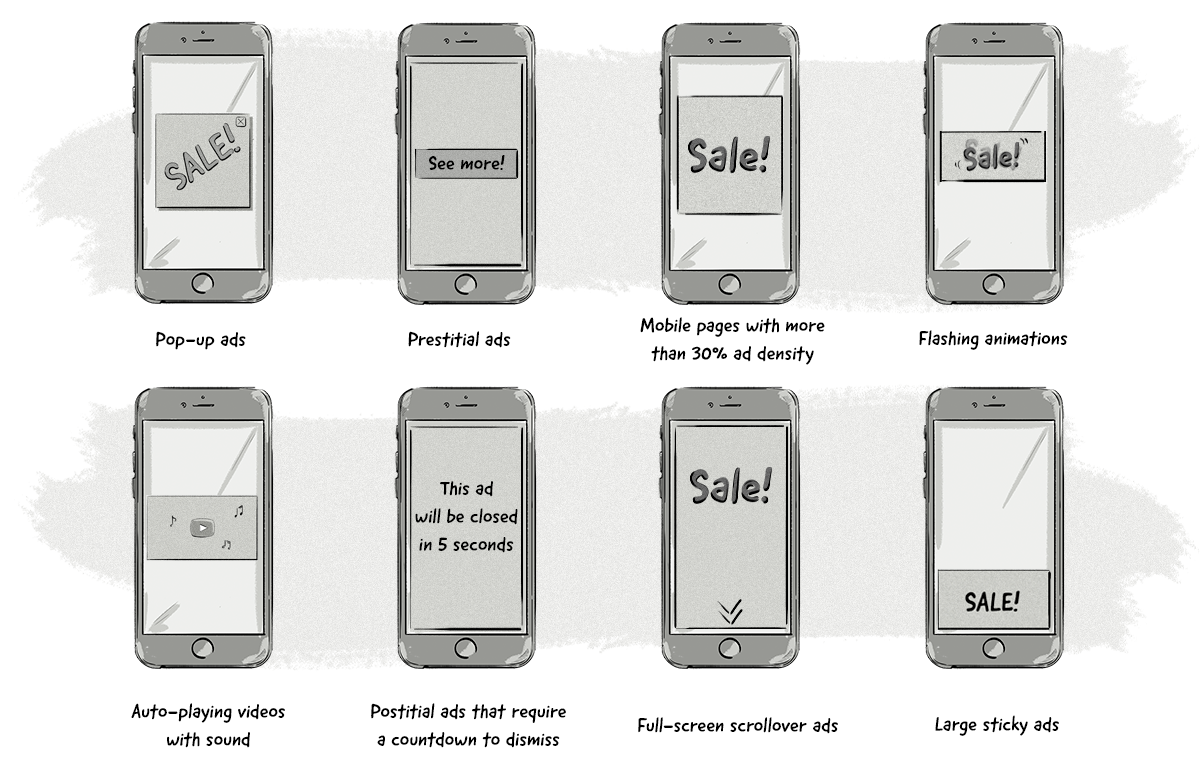

The filtered ads, according to www.betterads.org, include certain types of desktop ads:

- Pop-up ads

- Auto-playing videos with sound

- Prestitial ads with a countdown

- Large sticky ads

The types of mobile ad experiences least preferred by consumers and not complying by Better Ads Standard for ads on mobile devices include:

- Pop-up ads

- Prestitial ads

- Mobile pages with more than 30% ad density

- Flashing animations

- Postitial ads that require a countdown to dismiss

- Full-screen scrollover ads

- Large sticky ads

- Auto-playing videos with sound

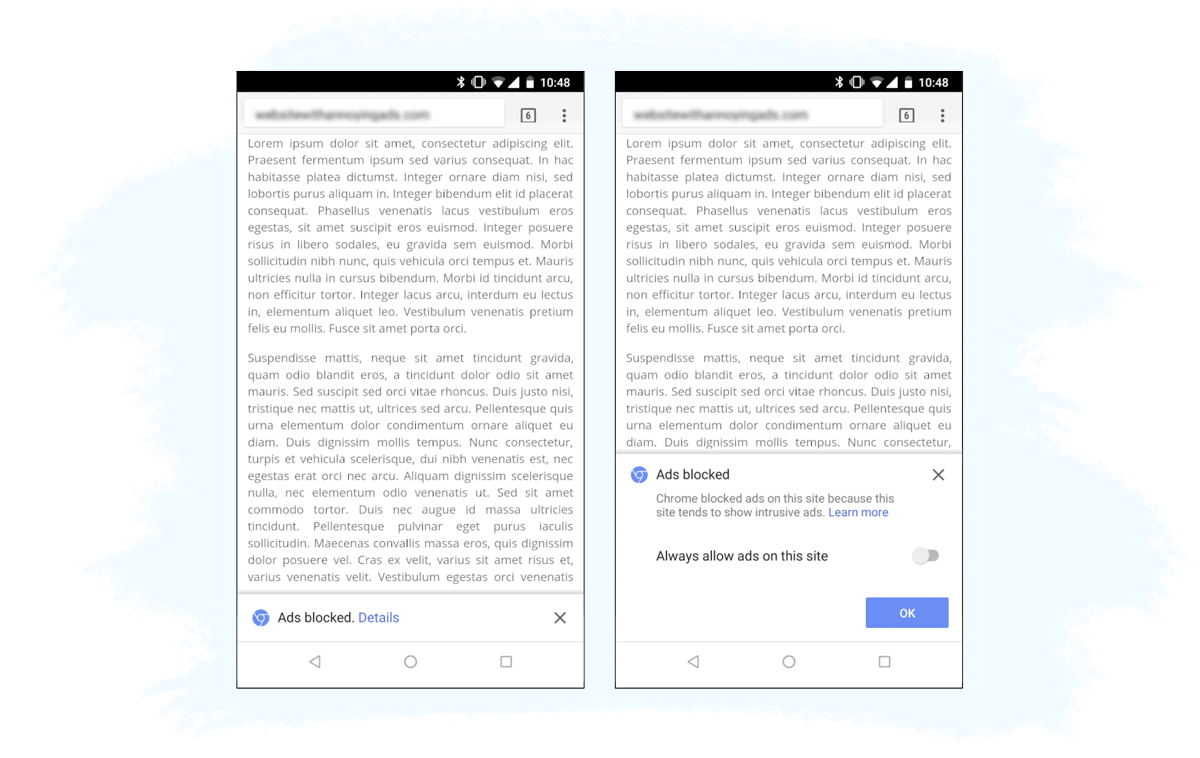

The Chrome filter is switched on by default and works in the following way:

- A Chrome user opens a new page.

- Chrome’s ad filter first checks the page against a list of sites that notoriously fail the Better Ads Standards.

- If the page is blacklisted, all requests for JavaScript ad tags or images ads will be blocked and won’t be displayed. To determine which requests are ad-related, Chrome uses EasyList patterns used by most available ad blockers.

From an Internet user’s perspective, when you open a website that is non-compliant with Better Ads Standards, you will see something like this:

Importantly, the filter doesn’t block all the ads; only the intrusive, poorly designed ads that get on people’s nerves the most. Ads that comply with Better Ads Standards will be displayed normally.

According to the standards proposed by the Coalition for Better Ads, the following kinds of ads – unlike in the case of using an ad blocker like Adblock Plus – will not be blocked by the Chrome filter:

- Autoplay video ads (without sound)

- Skippable prestitials

- Ads that initiate up to 12 seconds of scroll lag to ensure you see them

- Flashing ads

- Side-rail takeover ads

Chrome’s SameSite Cookies

On Wednesday, October 23, 2019, Google Chrome released a detailed blog post explaining changes about how cookies would be handled in the future.

The changes aim to give Chrome users more control over deleting third-party cookies, while keeping first-party cookies intact.

In short, website developers have to include a new “SameSite” attribute (specifically, SameSite=None) when setting a cookie to tell Chrome which cookies are to be used only by the current site or current URL that the user is on, and which ones are cross-site cookies.

Developers will also have to add the ‘Secure’ attribute as cookies will only be set via HTTPS.

Even though this attribute applies to Chrome, which was the first browser to support this attribute, it shouldn’t cause any issues in other browsers that don’t support it.

Setting cookies in this way will eventually help Chrome understand which ones are first-party and which ones are third-party.

In the future, Chrome could then ask users if they want to block third-party cookies. If the user says ‘yes’, then cookies created with `SameSite=None` will be blocked.

Chrome’s Privacy Sandbox

On August 22, 2019, Google announced a new initiative that aims to make the web more privacy friendly, but still allows online advertising to work in a limited capacity.

This initiative is known as Privacy Sandbox.

Google is quick to reiterate that blocking third-party cookies completely without providing a solid alternative (like what Safari and Firefox have done) is detrimental to the future of the Internet (and the back pockets of publishers). It also acknowledges that users are demanding more control over their privacy.

Instead of blocking third-party cookies altogether, Privacy Sandbox provides a secure environment for personalization while still protecting user privacy.

Here are the key things to know about Privacy Sandbox:

- It’s an open solution and Google has asked for feedback and input from other web browsers, publishers, and advertising technology (AdTech) companies on how to advance it.

- It is being positioned as a new web standard, rather than a new privacy feature.

- It will likely allow ads to still be relevant for users, but only anonymous and aggregated data would be available to AdTech companies and advertisers. Also, a lot more user data will stay on the device, instead of being passed on to AdTech companies.

- Google acknowledges that it can’t go it alone and will require input and feedback from other companies and organizations.

- It’s expected that Privacy Sandbox will go live in 2024.

Chrome’s Plans to Kill Off Third-Party Cookies and the Move To Privacy Sandbox

On Tuesday the 14th of January, 2020, Google Chrome made an announcement that most people in the online advertising industry never thought they would hear — Google Chrome will kill off third-party cookies by 2022.

This announcement follows in the footsteps of their previous initiatives (listed above) and is the next step in Google Chrome’s ongoing commitment to making the web a more privacy friendly place, while still allowing companies, including Google, to earn money from online advertising.

Here are the main things you need to know about this new announcement:

- Google Chrome plans to stop supporting third-party cookies by 2022.

- It will run a series of trials in 2020 to see how conversion measuring and personalization can work without using third-party cookies. This will involve using Privacy Sandbox (see above).

- The personalization element will probably be interest-based personalization on an aggregated level, rather than 1:1 personalization that has stood as the holy grail for advertisers and marketers for over a decade.

- The ultimate goal will be to replace third-party cookies used for ad selection and measurement with Privacy Sandbox.

As they’ve stated previously, Google Chrome doesn’t see strict privacy features, like those seen by Safari and Firefox, as the way forward for the Internet and online advertising.

Google Chrome feels that these approaches only encourage companies to create workarounds and develop techniques like device fingerprinting, which further diminish user privacy and provide little or no control.

Just like with other sandboxes used in computer security, Chrome’s Privacy Sandbox will execute advertising processes in a restricted environment, which is in stark contrast to how these processes are carried out today.

There are three parts to Privacy Sandbox:

- Replacing cross-site tracking processes — i.e. the ones currently powered by third-party cookies.

- Phasing out third-party cookies by separating first-party and third-party cookies via the SameSite attribute and turning off support for third-party cookies.

- Mitigating workarounds such as fingerprinting.

On Thursday, June 24, 2021, Google Chrome announced that it would be extending its planned sunset of third-party cookies by 2 years. Chrome said it will shut off support for third-party cookies starting from the middle of 2023.

Then, on Wednesday July 27, 2022, Google Chrome announced that it won’t start phasing out third-party cookies until the second half of 2024.

Although it’s still in development, Privacy Sandbox puts forward a completely new way of how online advertising works, particularly around identification, ad targeting, and measurement.

Identification in Privacy Sandbox

As part of its plans to improve user privacy, Privacy Sandbox won’t identify individual users. This also means there probably won’t be an ID that replaces cookies — i.e. no browser IDs.

This is the biggest change that the online advertising industry will have to get used to, as publishers, brands, agencies, and AdTech vendors have built their businesses around identifying individuals across the web via third-party cookies.

Although many AdTech vendors will turn to other identifiers such as first-party cookies, it’s impossible to rule out the possibility of Chrome limiting the use of first-party cookies and other techniques for identification, like what Safari has done with Intelligent Tracking Prevention (ITP).

Ad Targeting in Privacy Sandbox

The ad-targeting options in Chrome’s Privacy Sandbox will be fairly similar to the ones available today, but won’t rely on user-level identification.

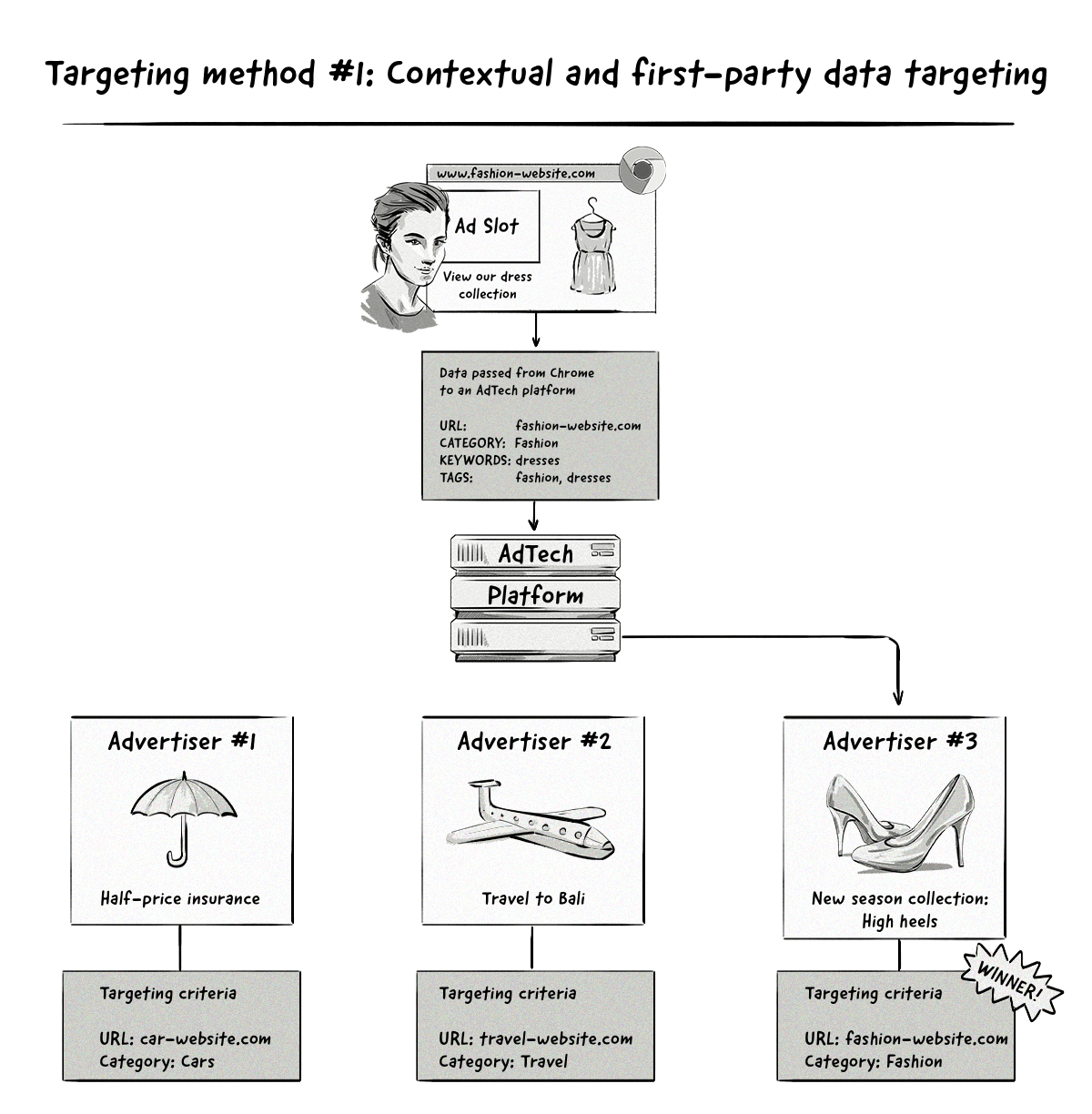

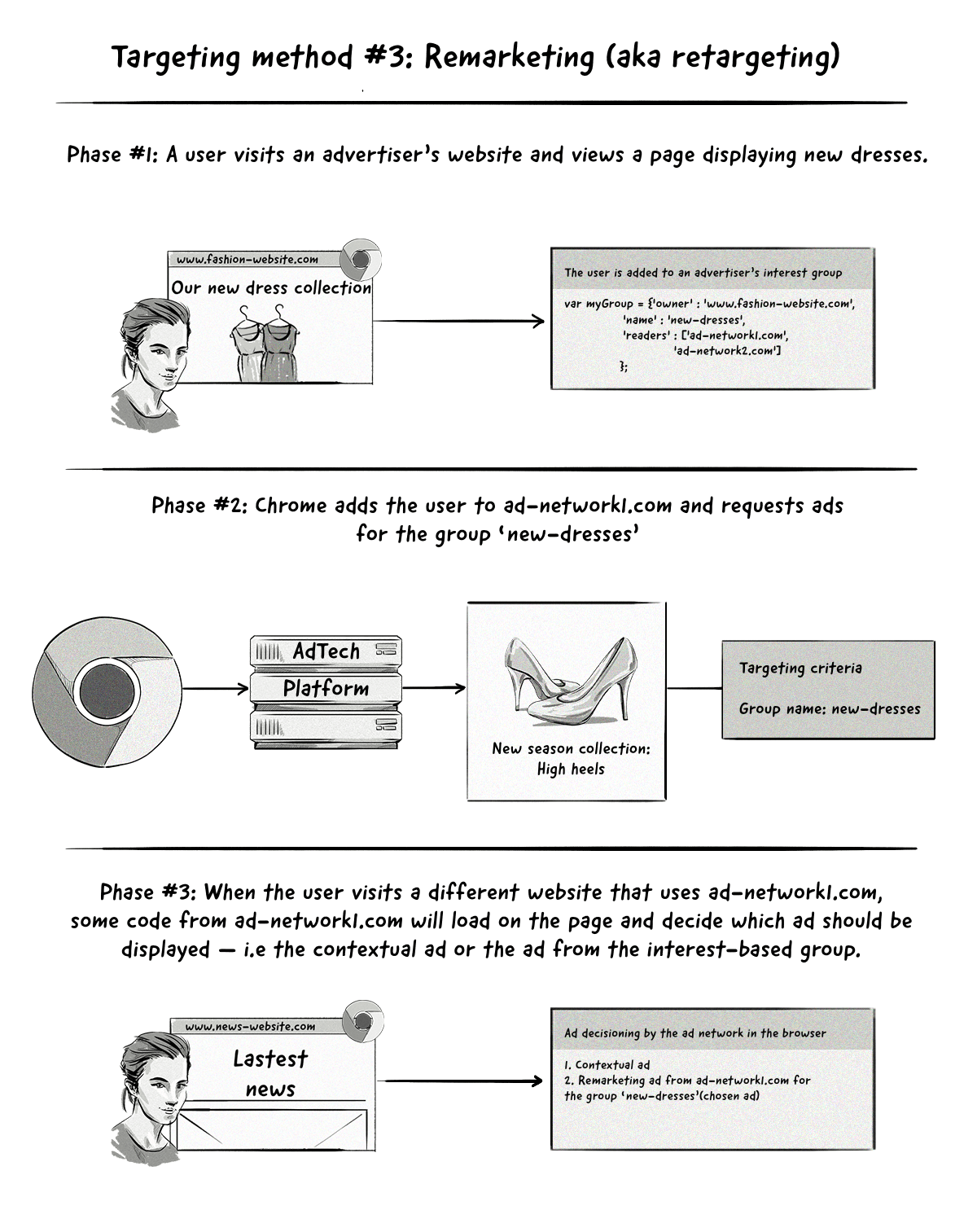

The main ad targeting processes in Privacy Sandbox are contextual and first-party-data targeting, topics-based targeting via Topics, and remarketing (aka retargeting).

With this method, users will be displayed ads that match the context of the page they’re visiting, similar to how contextual advertising works today.

The only difference is that Privacy Sandbox will be responsible for informing AdTech platforms about the context of the page, rather than the AdTech platforms themselves (e.g. via web crawlers and the user agent string).

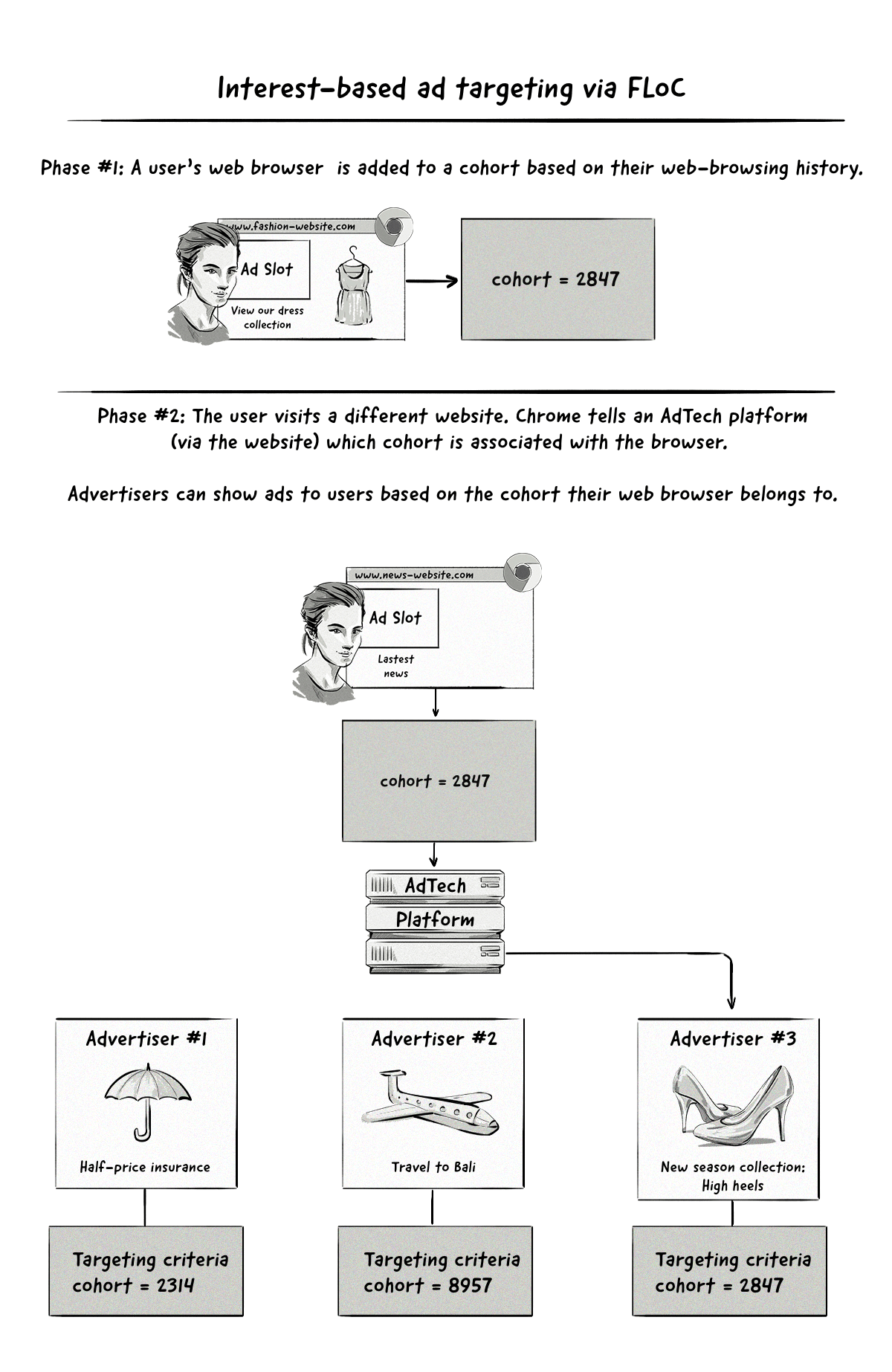

With interest-based targeting, a user will be added to a group based on the websites they visit. Advertisers will be able to target them based on the groups they belong to.

The important thing to note here is that targeting will be done on a cohort level, meaning no user data will be passed to AdTech platforms, just the name of the interest group they belong to. This new way of running targeted ad campaigns is in stark contrast to how it’s done currently.

Google Chrome announced on January 25, 2021, that it would make the FLoC API publicly available for testing in March 2021, and begin testing FLoC in Google Ads in Q2 2021. These tests were released in most countries, except for countries in Europe as Google is not yet sure if FLoC complies with the GDPR.

Based on the tests Google’s ad teams have conducted using FLoC, it claims that advertisers can expect to see at least 95% of the conversions per dollar spent when compared to cookie-based advertising for reaching in-market and affinity Google Audiences.

Then, on January 25, 2022, Google announced that it would be sunsetting FLoC and replacing it with a new initiative — Topics API.

Topics will enable advertisers to show ads to users based on the websites they visit, rather than the cohort they belong to. A classifier model will map website hostnames to topics and only subdomains and root domains will be included and not the full URL. For example, the website football.news.com will have the topic of football associated with it, but news.com/sport will have topics related to news.com associated with it.

There are currently around 350 categories that will be included in the Topics API, but it’s likely that this number will change.

The remarketing (aka retargeting) method is similar to the interest-based targeting method above, with the main difference being how the ad-decisioning process works.

With interest-based targeting, advertisers can show ads to users based on the interest groups they belong to.

With the remarketing method, the browser will send two ad requests to the AdTech platform — one containing contextual information and one referencing the interest group that the user belongs to.

The process Chrome’s Privacy Sandbox will use for remarketing is known as Two Uncorrelated Requests, Then Locally-Executed Decision On Victory (TURTLEDOVE).

The AdTech platform won’t know that these two ad requests are coming from the same user, hence the name ‘two uncorrelated requests’. The reason for this is to make it hard for AdTech platforms to identify users by connecting the time the two requests are sent.

The interesting thing about this proposed approach is that many of the key ad-decisioning and even auction mechanics will be conducted clientside (i.e. in the Chrome browser) instead of server side by AdTech platforms.

Other Proposals in Chrome’s Privacy Sandbox

Apart from the standards mentioned above, there are many others that have been put forward by Google and other companies, including AdTech companies, advertisers, and publishers.

Some of these proposals include:

SPARROW: A proposal from Criteo in response to Chrome’s TURTLEDOVE.

Dovekey: A follow-up proposal to Criteo’s SPARROW from various teams at Google.

PARROT: A proposal from Magnite that’s designed to maintain the privacy aspects of TURTLEDOVE but put control of the auction decisioning in hands of publishers by utilizing Fenced Frames (another proposal from the Google Chrome team).

TERN: a proposal from AdTech company NextRoll. The goal of TERN is to propose improvements to TURTLEDOVE based on information collected from GitHub issues and repos.

Fenced Frames: An API proposal created by Google engineers that would allow ads on a web page to load without the rest of the page knowing what ad is being displayed. The Fenced Frames API would be used to communicate with other Privacy Sandbox standards, like TURTLEDOVE, to show interest-based ads.

FLEDGE: A proposal from Google that’s designed to be an early prototype of ad-serving processes in TURTLEDOVE. FLEDGE also incorporates components of the proposals made by independent AdTech companies (i.e. the ones listed above).

A full list of proposals can be found on the W3C’s Web Advertising Business Group Github repository.

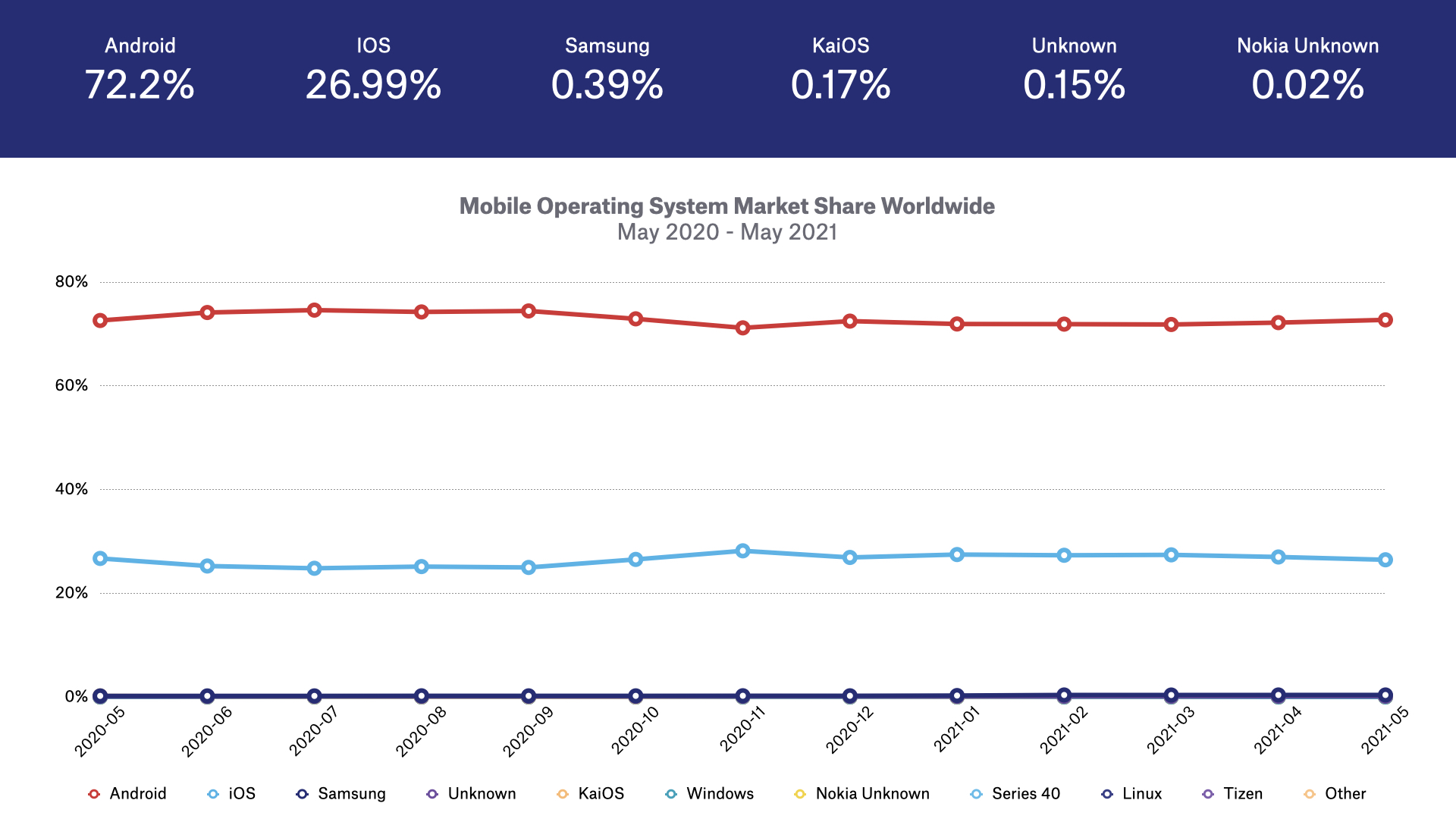

Mobile IDs

Although most of the privacy changes over the past few years have been focused on web browsers, they are now starting to enter the in-app mobile world.

The two main mobile operating systems are Google’s Android and Apple’s iOS.

Just like in the web-browser world, Apple has made a number of changes to iOS to increase user privacy over the past few years, including:

Limit Ad Tracking (LAT): An option that allows iOS users to opt out of targeted advertising. When enabled, the user’s IDFA will be zeroed out (i.e. the random numbers and letters will be replaced with zeros) when accessed by apps and AdTech companies.

Opt out of location-based Apple Ads: This option allows iOS and macOS users to opt out of location-based ads served by Apple.

Grant or deny access to location data: The new release of iOS 13 brought with it an update to location data controls.

Firstly, users were periodically shown messages informing them of certain ads that were using their location data in the background (i.e. when not actually using the app in question).

Secondly, Apple presented users with a choice about whether an app could use their location data.

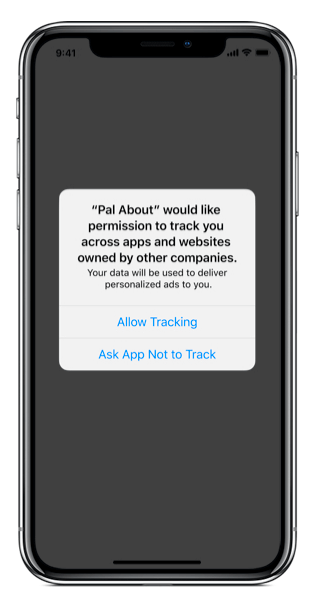

Apple’s App Tracking Transparency (ATT) Framework

During its Worldwide Developers Conference (WWDC), Apple announced that it would be introducing a series of privacy changes in iOS, iPadOs, and tvOS.

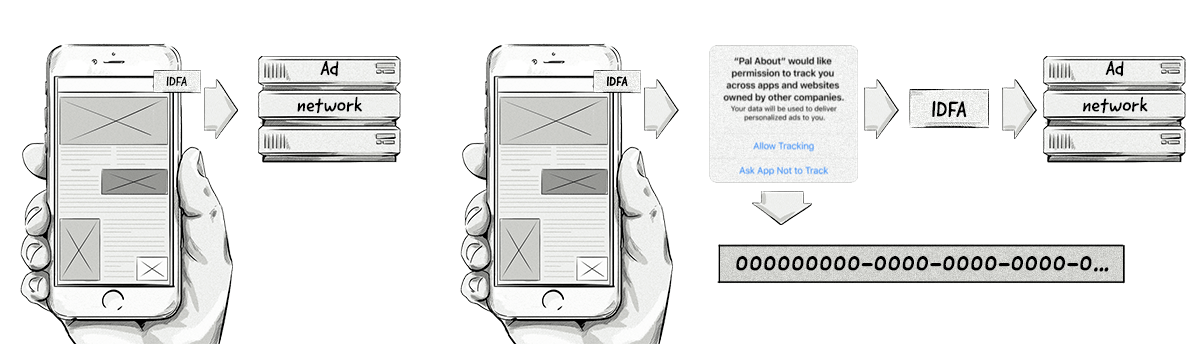

One of the main changes was to change how its mobile identifier (IDFA) is accessed by app developers, AdTech companies, and mobile measurement platforms (MMPs).

As of iOS 14.5, iPadOS 14.5, and tvOS 14.5, if app developers, AdTech companies, and MMPs want to collect a user’s IDFA, they’ll have to obtain consent via Apple’s AppTrackingTransparency (ATT) Framework.

The framework involves showing users a message, similar to the one below, asking them if they can track them across different apps.

If users accept, then their IDFA will be collected. If they reject it, then the IDFA will still be collected but will be zeroed out, making it useless from an identification point of view.

The image on the right illustrates how the IDFA can be accessed in iOS 14.5

Apple’s ATT framework has a very similar impact to the loss of third-party cookies in web browsers as it limits cross-app identification. In turn, this makes personalized ad targeting, retargeting, measurement, and attribution very limited.

Although Apple hasn’t put forward a solution to ad targeting, it has released a solution for app install attribution via its SKAdNetwork.

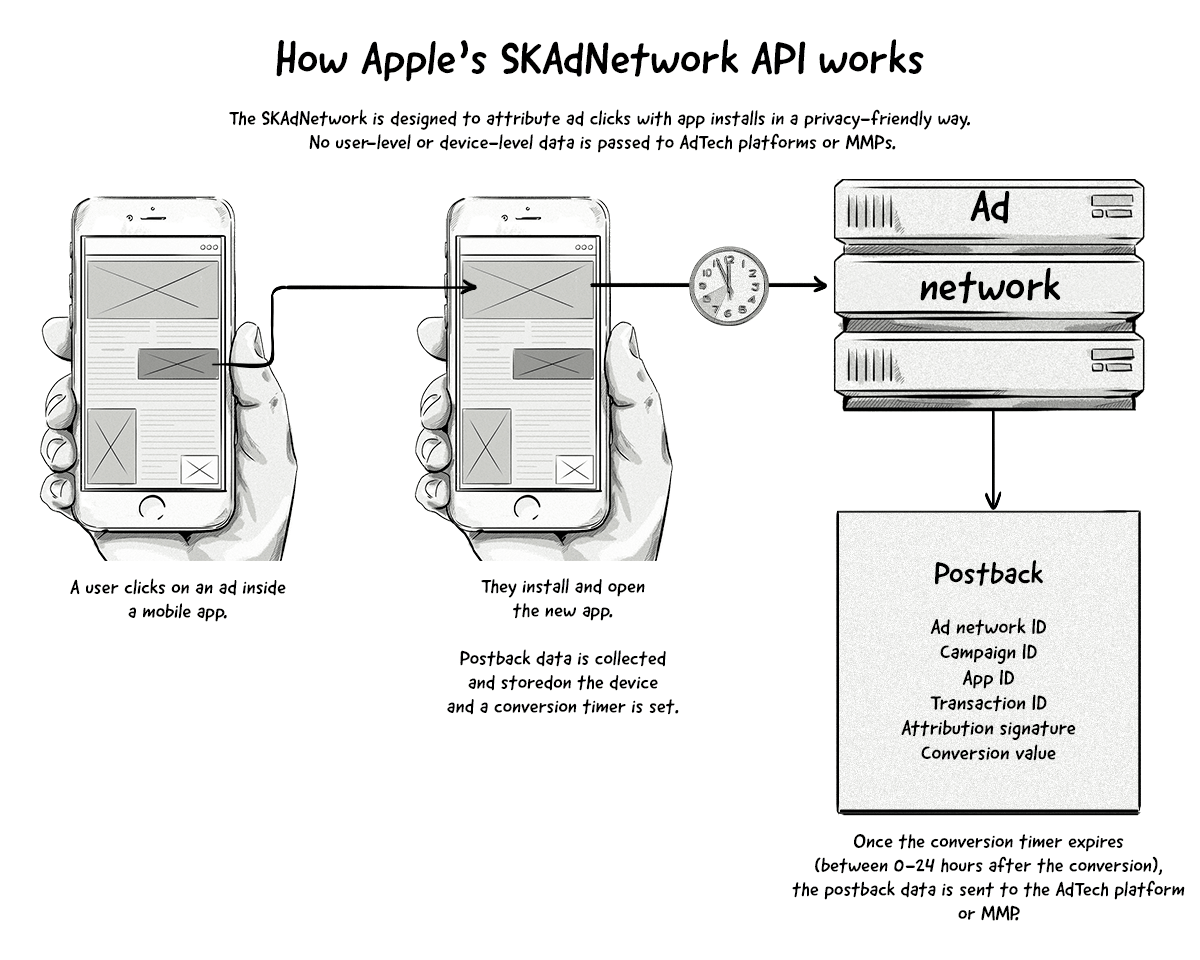

Apple’s SKAdNetwork

Apple’s SKAdNetwork aims to provide conversion data to advertisers but without revealing any user-level or device-level data. It’s Apple’s version of a privacy-friendly way to attribute app installs.

Here’s how Apple’s SKAdNetwork will work:

A couple of points about the SKAdNetwork:

- The IDFA won’t be passed to AdTech platforms or MMPs, even if the user has opted in.

- All attribution data will pass through SKAdNetwork and then onto the AdTech platform or MMP. In iOS 15 and iPadOS 15 onwards, advertisers will also be able to receive the postback information.

- SKAdNetwork will only attribute app installs (via the last-click model) and not view-through conversions.

- Campaign IDs are limited to 100 per AdTech platform (e.g. ad network or MMP).

Apple’s Privacy Changes in iOS 15 and iPad 15

With the release of iOS 15, iPad 15, and watchOS 15, Apple will introduce a feature known as the App Privacy Report.

The App Privacy Report will give users more insights into how apps use things like their location, photos, camera, microphone, and contacts.

The report will show users how apps have accessed that information in the past 7 days and can deny access to that information by changing the settings.

The App Privacy Report will also show users which third-party domains the app has been contacting so that users can see which companies their data is potentially being shared with.

Google’s Android Advertising ID (AAID)

Although Google hasn’t announced any significant changes to its Android advertising ID (AAID), it has hinted at making some changes in the future.

Google recently announced that it will require app developers to include privacy information in their Google Play Store listings, similar to the privacy information displayed in Apple’s App Store listings.

Then in July 2021, Google announced that it would stop passing on its AAID if the user had opted out of personalized advertising. These changes went live with the release of Android 12 in the later part of 2021. While this is considered a privacy change, it’s not as stringent as the ones released by Apple.

Ad Blockers

Ad blockers emerged in the mid-2000s and have risen in popularity over the past decade due in part to the growing concerns over user privacy and the pure annoyance of some ads (e.g. popup ads).

Although there are several ad-blocking methods, the most popular method by far is via web browser plugins like AdBlock Plus, Ghostery, and uBlock.

How Do Ad Blockers Work?

Most ad-blocking plugins work by preventing JavaScript and other elements from loading. This is achieved by adding domains used to serve ads to a blacklist and by identifying elements used for displaying ads, such as class=”advertisement”, class=”banner_ad”, and alt=”ad” from loading.

Because most ad blockers stop AdTech JavaScript tags from loading, they not only stop ads from being displayed but also stop third-party cookies from being created. This means publishers miss out on ad revenue.

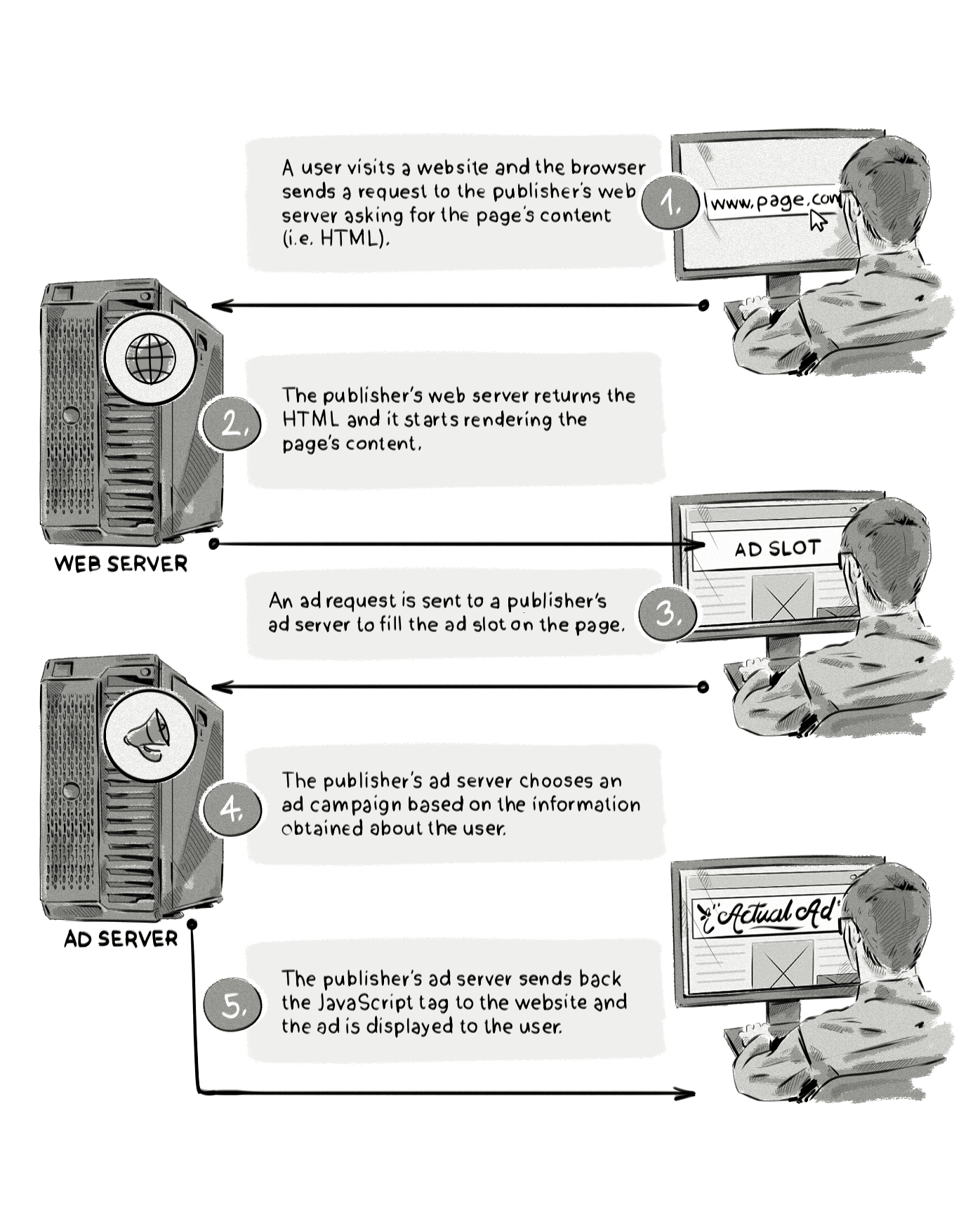

To highlight how ad blockers work, below we illustrate the normal ad-serving process where an ad is sent from an advertiser and displayed to a user on a website, and then how the process looks when an ad-blocking plugin is used.

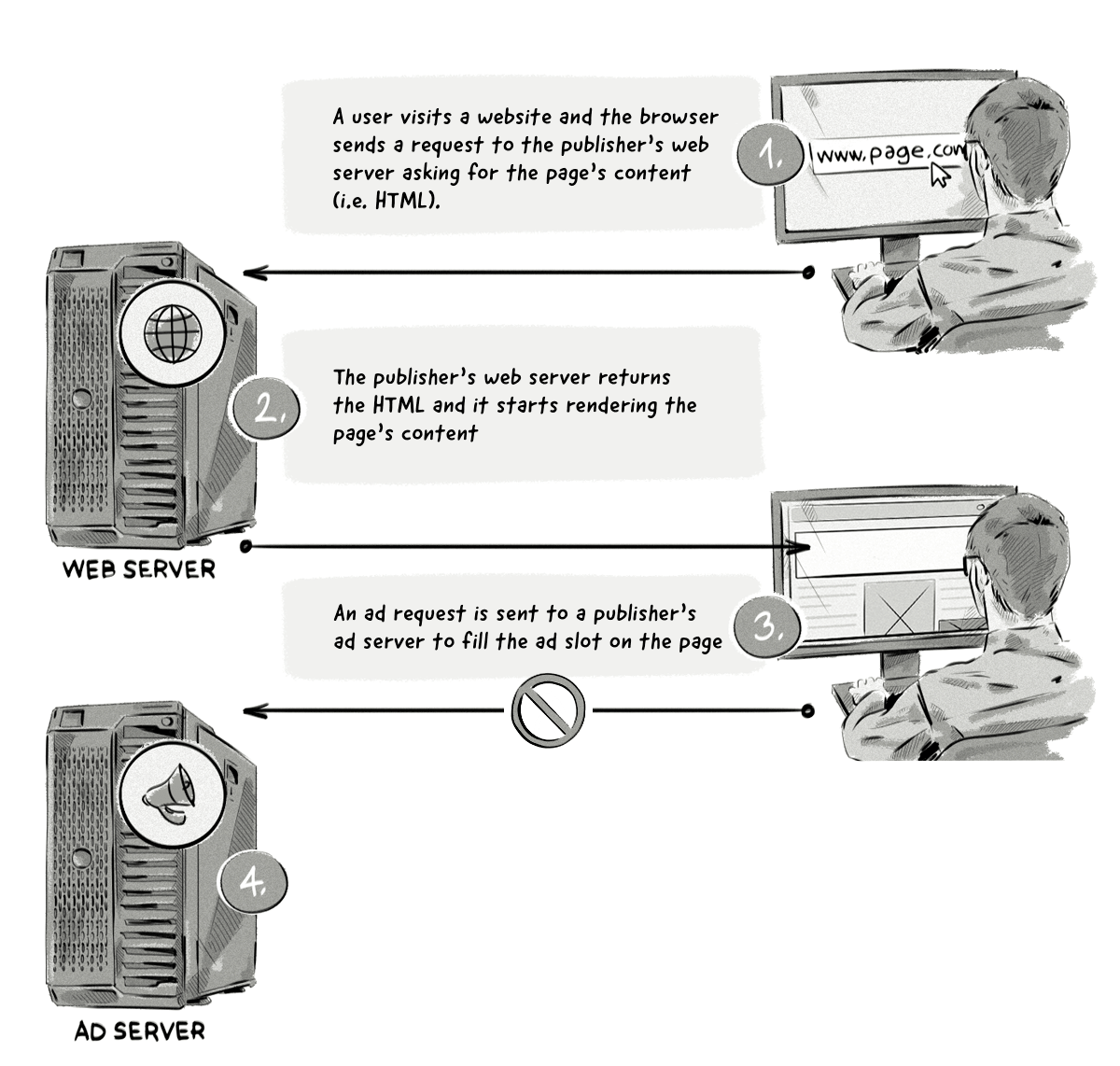

And here’s the same process but with an ad blocker:

Here’s a step-by-step explanation of what’s happening in the image above:

- A user visits a website and the browser sends a request to the publisher’s web server asking for the page’s content.

- The publisher’s web server returns the HTML and it starts rendering the page’s content.

- The ad blocker extension scans the HTML and:

- Blocks the requests to load external resources, such as an ad request to the ad server domain (the ad request is not made).

- Hides certain HTML elements from appearing, such as class=’’ad’’.

The Impact Ad Blockers Have On The Digital Advertising Industry

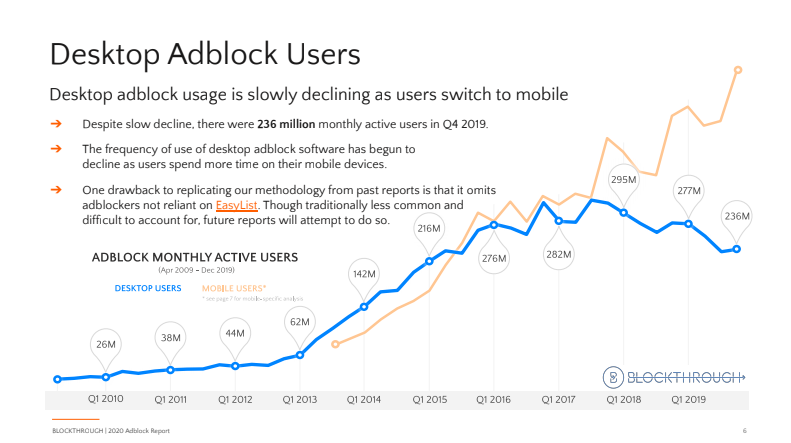

The impact of ad blockers on publishers is immediate, severe, and costly. It’s estimated that ad blockers will cost publishers $27 billion in lost ad revenue in 2020.

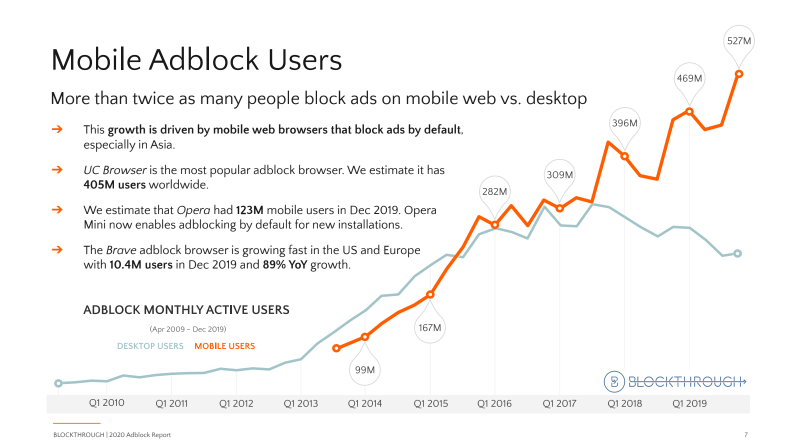

According to Growth of the Blocked Web 2020 PageFair Adblock Report by Blockthrough, over 615 million devices (desktop and mobile) worldwide have some sort of ad blocking software installed.

What Can Publishers Do About Ad Blockers?

When it comes to addressing the issue of ad blockers, publishers first need to find out if a user is using ad-blocking software, and then use a variety of tactics to handle it.

How can publishers detect if someone is using an ad blocker?

Although it’s difficult to bypass ad-blocking software, it’s possible to determine whether someone is using an ad blocker by testing whether particular elements of the page have been displayed.

Typically, testing for the presence of an ad blocker involves adding a “bait” script — a tiny piece of code that an ad blocker is likely to interpret as an ad — to the publisher’s website. This bait script could contain a class name like “banner_ad”, which would likely be blocked by an ad blocker.

Examples of bait scripts and anti-ad-blocking scripts

Ad-block-detection scripts that are based on the aforementioned “bait” method take just a couple lines of code to implement. There are a few providers offering ready-made ad-block detecting scripts:

Detectadblock

Detectadblock.com proposes a method that requires a piece of JavaScript code to be saved. The method involves a hidden <div> section saved to a file called “ads.js”, placed in the root directory of the website:

var e=document.createElement('div');

e.id='RZfrHsidDwbG';

e.style.display='none';

document.body.appendChild(e);Publishers place the following JavaScript within their website’s HTML source code just above the </body> tag. Its purpose is to check if the hidden DIV created within “ads.js” exists (ads are allowed) or not (ads are being blocked).

<script src="/ads.js" type="text/javascript"></script>

<script type="text/javascript">

if(document.getElementById('RZfrHsidDwbG')){

alert('Blocking Ads: No');

} else {

alert('Blocking Ads: Yes');

}

</script>IAB Script

The Interactive Advertising Bureau (IAB), an advertising-business organization that develops industry standards, runs its own tech lab and has also proposed its own ad-block-detection script. It creates a set of “bait” DIVs likely to be blocked by browser-based ad-blocking tools. The script is really simple to set up, and the IAB runs its own Github page (https://github.com/InteractiveAdvertisingBureau/AdBlockDetection) where you can find details about its inner workings.

BlockAdBlock

BlockAdBlock is a community-developed anti-ad-blocking script. Similar to the aforementioned methods, it’s very simple and effective.

The bait used by BlockAdBlock looks like this:

baitClass: 'pub_300x250 pub_300x250m pub_728x90 text-ad textAd text_ad text_ads text-ads text-ad-links'This means it will trigger ad-blocking software by referencing typical names and popular IAB-recommended ad-image sizes: 300x250px, 300x250px, and the skyscraper 728x90px. All these strings are referenced in Easylist. The script then detects whether the elements were displayed on the page.

How can publishers deal with ad blockers?

Detecting ad blockers is half the battle. Once a publisher determines that a user is using an ad blocker, they can then decide how to deal with it.

In March 2016, the IAB released its Publisher Ad-Blocking Primer, a 23-page document laying out seven tactics publishers can use to combat the ever-increasing ad-blocker problem.

The primer also includes a process known as DEAL, which the IAB suggests publishers follow when having conversations with visitors who use an ad blocker:

The DEAL process and the Publisher Ad-Blocking Primer are just a few of the recent initiatives released by the IAB Tech Lab to combat ad blockers.

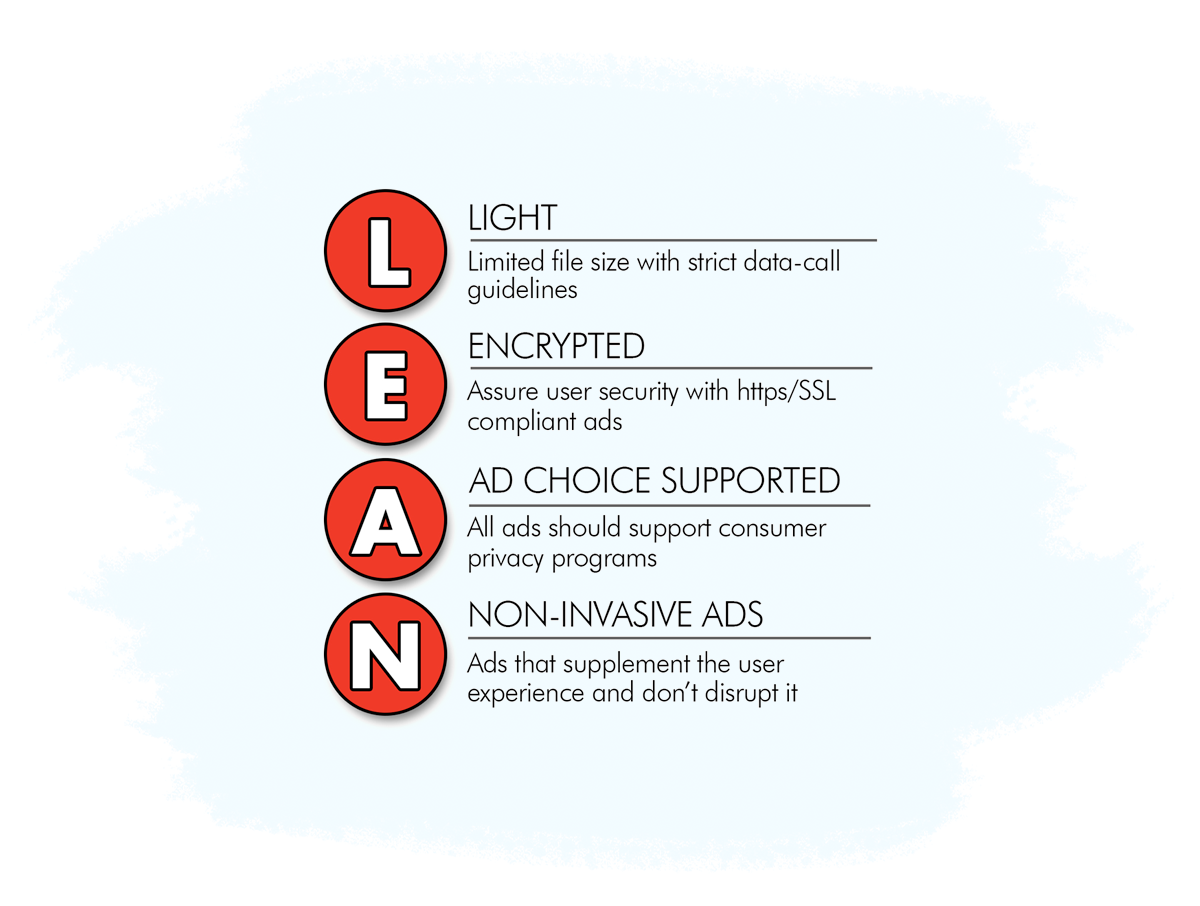

Others include the ad-blocking detection script (mentioned above) and the LEAN Ads Program, which aims to ensure ads complement and even enhance the user experience, rather than hinder it:

7 Tactics Publishers Can Use to Deal With Ad Blockers

The tactics provided by the IAB cover a range of possible implementations and can be used separately or in conjunction with others.

All of the seven recommendations listed by the IAB come with their own risks and benefits. The IAB suggests publishers weigh up the risks and benefits and consider the type of relationship they have with their audience before deploying a tactic.

Here’s a brief recap of the items mentioned in the Publisher Ad-Blocking Primer and some examples of what they look like in action.

1. Notice

This tactic involves publishers detecting an ad blocker and then taking one or more of the following actions:

Educating and informing the user about the negative implications of ad blockers and the value of advertising (e.g. free content in exchange for viewing an ad).

Requesting the user disable the ad-blocking software in order to continue.

Asking the user to donate money to avoid seeing ads.

Telling the user that if they want to use an ad blocker, their experience will be limited.

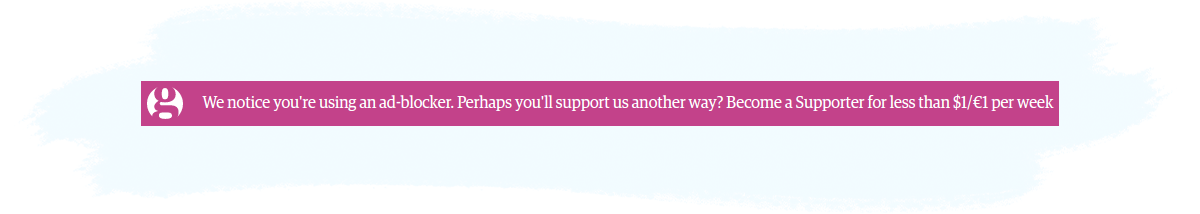

The aim of the Notice tactic isn’t necessarily to force the user to disable their ad blocker, but to start a conversation regarding their ad-blocking choices and encourage them to take a certain action. The Guardian is just one publisher out of many using the Notice tactic:

2. Access Denial

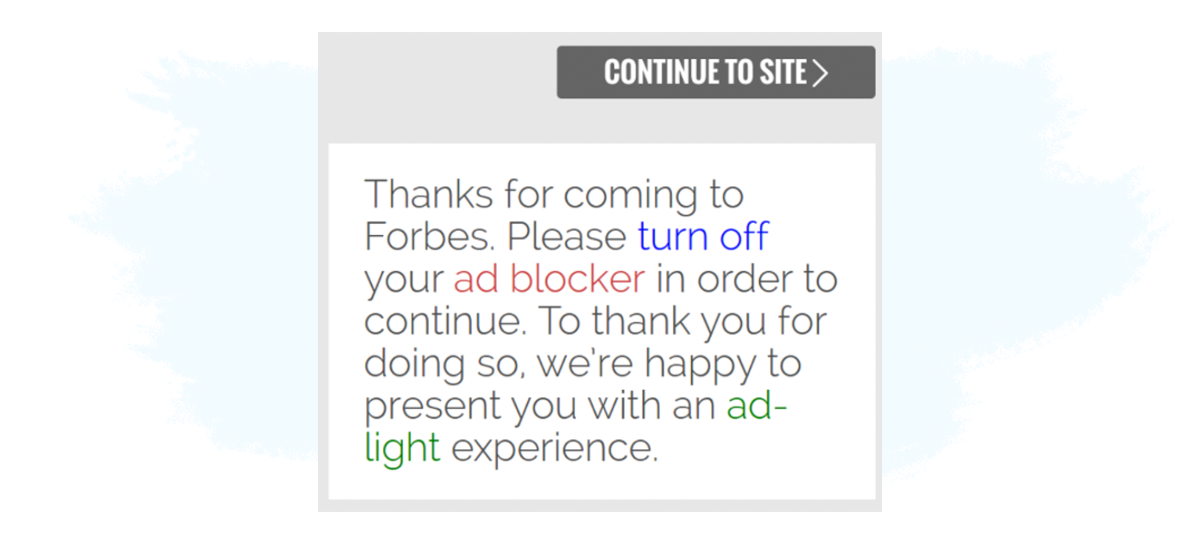

Access denial goes one step further by restricting access to the site (or parts of the site) until the user has completed an action proposed by the publisher — e.g. switching the ad blocker off, subscribing, registering, or making a donation.

An example of the Access Denial tactic can be found on Forbes:

3. Tiered Experience

Unlike the above tactic that denies the user access to content, the tiered experience method works by delivering a limited or modified experience to a user who has an ad blocker installed while delivering the full experience to a user who doesn’t.

For example, a publisher may only allow users with an enabled ad blocker to read five articles per month, but let users without ad blockers read a higher or unlimited number of articles.

This tactic is similar to paywalls publishers use to encourage visitors to take out a paid subscription:

4. Payment From Visitors

The payment from visitors tactic can relate to both monetary and non-monetary payments.

For example, a publisher may ask the visitor to pay a small fee to access the content or provide their email address.

Examples include:

Subscription: A visitor pays or provides some information (e.g. a name and email address) for continued access to the content, just like in the example below from bild.de.

Punch-Card: A visitor pays for a set number of accesses (e.g. $10 for 10 articles).

Timed Pass: A visitor pays for access for a limited period of time (e.g. $10 for one month).

Members-Only Section: A visitor pays for access to content or features only available to paying members.

5. Ad Reinsertion

Publishers can also resort to ad reinsertion, which is arguably the least ethical and user-friendly way to fight ad blockers.

The term describes the practice of finding ways to serve ads to users that have an ad blocker installed. Ad reinsertion may be done with or without the permission of the adblock software provider.

While this technique may actually stop ads from being blocked (at least for some time), actual short-term and long-term implications of ad reinsertion are still unknown—in fact it’s advertising to people who explicitly don’t want to be advertised to.

The method is a constant cat-and-mouse game that may involve a lot of effort on the publisher’s side, but ultimately bring little benefit.

Ad reinsertion is comprised of three main methods:

Obfuscation: This method attempts to avoid ad-blocking software by changing the names of the ads and their location on the page.

In browser: Similar to above, this method aims to avoid being picked up by ad blockers by using software in the browser to change the requests sent to the ad resources.

On server: Using a process known as server-side ad stitching (a.k.a. ad insertion or dynamic ad insertion), this method delivers the ad from the same server as the content or service, which avoids detection from ad blockers.

6. Payment to Ad Blocker Companies

All of the aforementioned tactics relate to technology solutions, whereas this is more of a business solution to the ad-blocker problem. Payment to ad blocker companies involves buying your way onto ad-blocker whitelists so your ads are not blocked by the software.

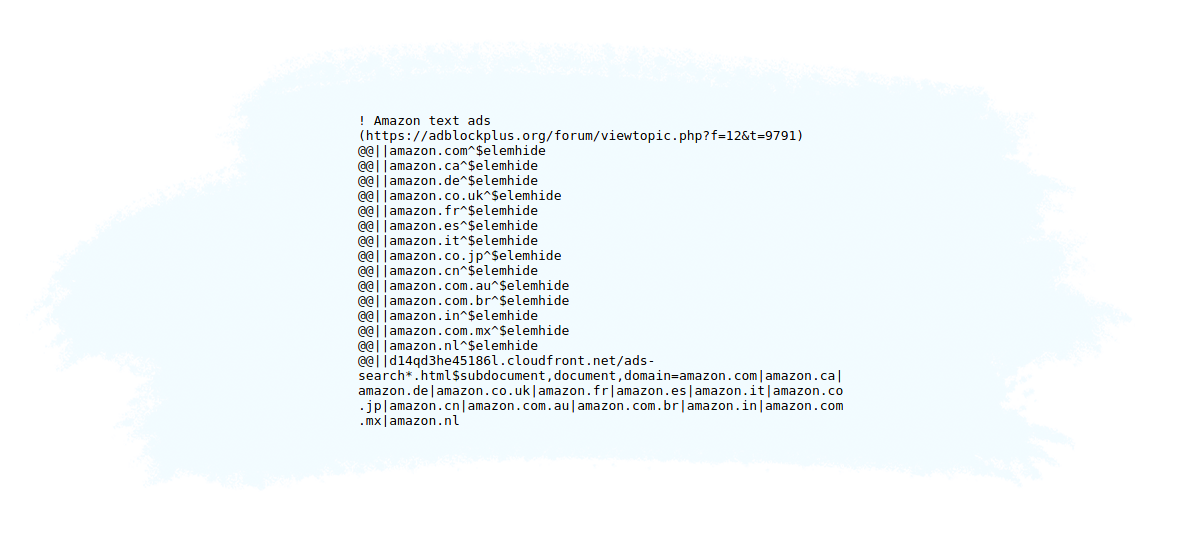

Adblock Plus (ABP), one of the most popular ad blockers, has created a program called Acceptable Ads Program, in which companies can apply to its whitelist so their ads can still run even if the ABP software is active.

Here’s a snapshot of ABP’s whitelist:

In the image above, you can see that Amazon ads are on the whitelist, which means they should still appear even if the ABP software is active.

7. Payment to Visitors

Similar to the previous strategy, this one involves paying or rewarding visitors for their time spent with advertising. Examples of this include sharing a portion of ad revenue with users and giving them extra playing time if they view ads on a mobile game.

8. Native Ads

Another effective way to circumvent ad-blocking software is to display native ads.

Native ads are inherently more difficult to detect, as the ad content is implemented in such a way to largely resemble the original content on the website.

Native in-feed ads match the original editorial content in form and function, making them difficult to detect.

This is a very effective way to monetize content, and is used by some of the biggest players in the industry, including Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter, and Instagram. Major news media—including Time, Forbes, The Wall Street Journal, and The New York Times, quickly sensed potential and jumped on the native bandwagon.

However, because most native ads are served via third-party AdTech platforms and contain similar elements to banner ads (e.g. class=”native-ad”), there’s still a chance that they’ll be detected and blocked.

Opting Out Of Online Behavioral Advertising

Online behavioral advertising (OBA) simply means targeting online consumers with ads that align with their online behavior — typically, what types of websites they visit.

So for example, if you regularly visit websites about cooking, you will more than likely see ads about cooking, such as kitchen products and cookbooks.

Behavioral targeting helps advertisers display ads that are relevant to your needs and interests. However, some consumers wish not to receive these types of ads as they don’t like the fact that companies collect information about them.

How can Internet users opt-out of behavioral or targeted online advertising?

There are 4 main ways online users can opt-out of behavioral or targeted advertising.

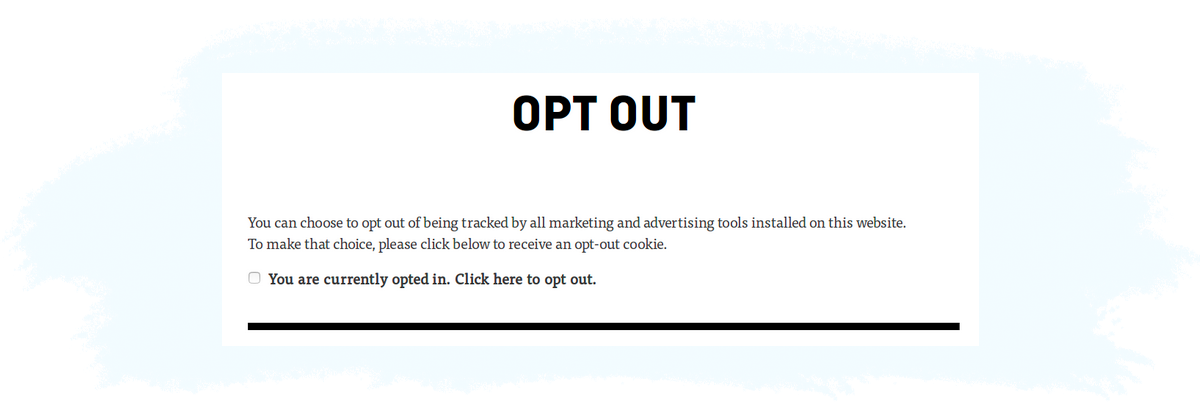

Solution # 1: Unchecking the opt-in option found on a web page.

Some websites include an option for you to opt-out of marketing for that site. It’s important to note that by doing so, you are only opting out of this particular site and it won’t opt you out of other sites.

When a user opts out of a particular site, a cookie is set in the first-party cookie of the publisher. This cookie is then checked, typically by a tag manager, before any tags get served. If the opt-out cookie is detected, the tags aren’t fired.

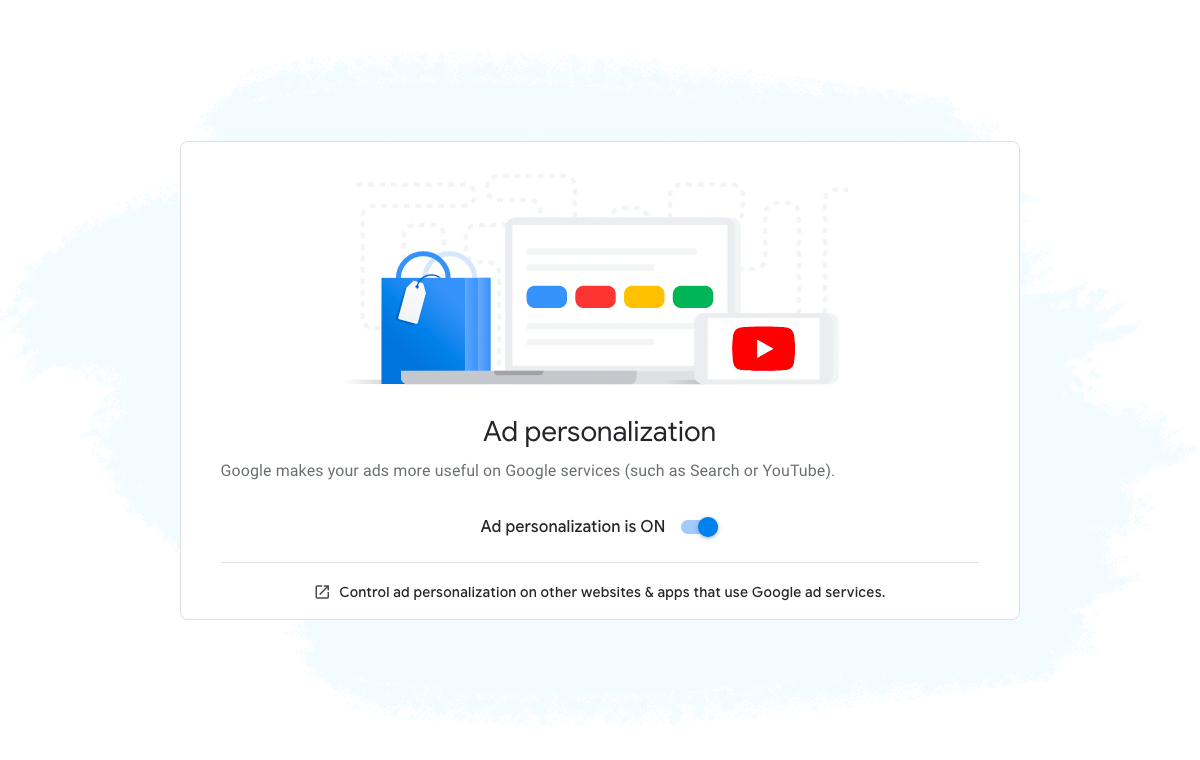

Solution #2: Turning off the personalization feature on popular search engines (i.e. Google, Bing, Yahoo!) and other sites (e.g. Amazon and Facebook).

You can not only opt out of behavioral targeting but can also change the settings in your web browser so that you are displayed ads that are more relevant and of interest to you.

If you turn this option off, then you will still see ads, but they will be general and location-based ones, rather than ones that match your interests.

When a user opts out from search engines and accounts, the opt-out request is set at the account level, rather than saved as a first-party cookie. So when you’re logged in to the site, the website (e.g. Facebook, Google, Amazon, etc.) knows that you have opted out and therefore doesn’t personalize the ads or pass additional information about you to the ad platforms.

However, this method of opting out does not prevent these companies from collecting data about your behavior; it just means they won’t use data collected about you for ad personalization.

Solution #3: Requesting AdTech vendors and their clients to not track you across their products.

This is a similar process to the first point, however, opting out of the Ad Tech & MarTech products will apply to all websites that use that particular software or platform.

This method works in a similar way to the first solution, except instead of creating a first-party opt-out cookie on the publisher’s side, a third-party opt-out cookie is created on the AdTech vendor’s side. Organizations like the NAI (mentioned below) allow users to opt out of behavioral targeting from all the members (i.e. vendors) in their organization.

The third-party cookie’s value is then sent with every request to the participating vendors advising them that the user has opted out and therefore shouldn’t apply behavioral targeting in ads or collect behavioral data.

While this method allows users to opt out from multiple companies at once, it’s up to vendors as to whether they respect the user’s decision to opt out or not, but since it’s their opt-out cookie, they generally should uphold the user’s decision.

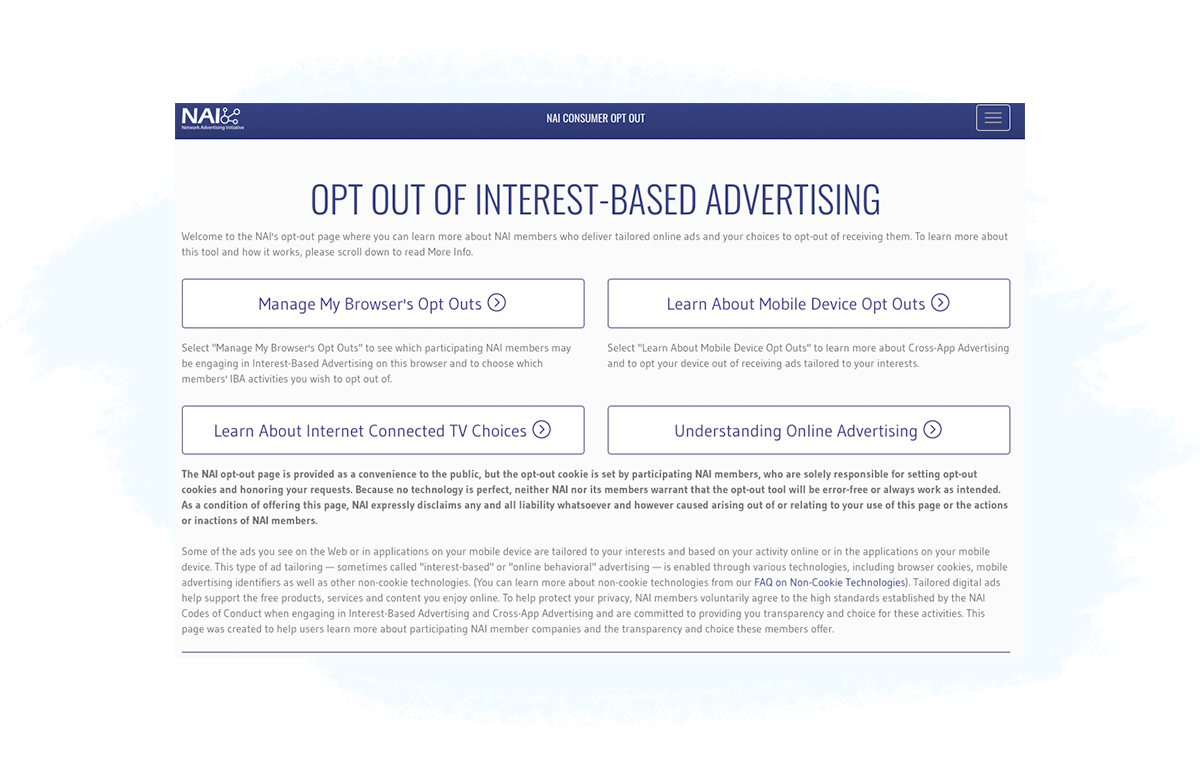

Solution #4: Opt out of behavioral advertising via Advertising Organizations

There are a couple organizations that exist to help online users control how their data is collected and used for activities such as behavioral targeting.

The two main organizations are the Network Advertising Initiative (NAI) and the Digital Advertising Alliance (DAA).

The Network Advertising Initiative (NAI) is the leading self-regulatory association consisting of third-party digital advertising companies.

The NAI is a non-profit organization and aims to promote the health of the online ecosystem by maintaining and enforcing high standards for data collection and use for advertising online and in mobile.

The NAI provides a tool that allows online users to opt out of behavioral advertising.

The NAI opt-out tool:

- Only affects behavioral advertising.

- Opts users out of behavioral targeting from NAI members only.

- Doesn’t delete cookies nor remove online ads completely.

- Allows users to choose which companies to opt-out of.

- Sets an opt-out cookie in the user’s browser for each of the companies the user selects.

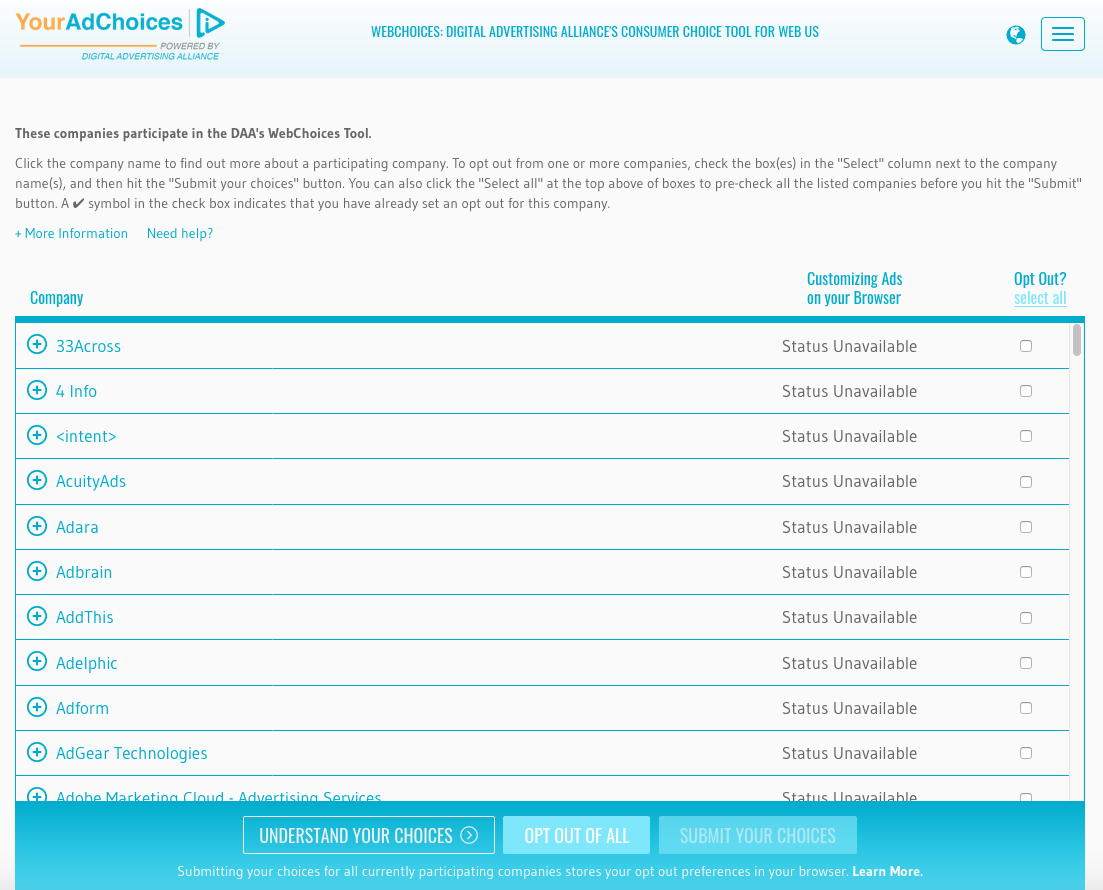

The Digital Advertising Alliance (DAA) is an independent non-profit organization led by leading advertising and marketing trade associations.

The purpose of the DAA is to establish and enforce responsible privacy practices across the digital advertising industry to provide consumers with enhanced transparency and control.

The DAA is the organization behind the YourAdChoices initiative, which is represented by the icon on some display ads:

Through its YourAdChoices initiative, the DAA offers a browser tool, known as WebChoices Tool, that allows online users to opt out of behavioral targeting from DAA’s participating companies.

Just like with the NAI opt-out solution, if a user deletes their cookies, then they will have to go through the opt-out process again.

Solution #5: Disabling third-party cookies from being saved in your web browser and activating the Do-Not-Track feature.

You can disable third-party cookie tracking and enable the Do Not Track option in your web browser by adjusting the privacy preferences in the web browser’s settings.

The Do Not Track (DNT) option requests that a web application disable either its tracking or cross-site user tracking of an individual user.

The DNT header is automatically attached with every HTTP request that the user’s browser makes, but it’s up to the vendor receiving the request (e.g. ad server, SSP etc.) to honor it or not.

Apple’s Safari no longer supports DNT as it provides little protection over a user’s online privacy.

The Implications Of Opt-Out Solutions

There are 2 main implications opt-out solutions have on the online advertising industry:

1. Lower ROI for advertisers.

The implications of opt-out solutions affects both the advertiser and publisher because if more and more users decide to opt out of behavioral advertising, then this will devalue the publisher’s audiences & traffic and will cause their inventory to be less valuable.

For advertisers, their ROI will be impacted as their ads won’t be shown to engaged or interested users.

2. Lower revenue for publishers and less opportunities to monetize the Internet.

Currently, publishers and app developers display ads as a way to monetize their content and apps, most of which are provided for free. The increase in opt outs will result in publishers and app developers charging for their content and apps.

There are quite a few publishers, mainly large news sites, that already charge for their content, but this type of monetization model could increase. Similarly, app developers could start charging for their apps, which could lead to a decrease in free apps available to users.

Differing Views on Data Collection

There are many different views and opinions on the way users’ data is collected, shared, and sold online.

Some believe that if the tracking is only for advertising purposes, it poses no great risk to their privacy, while others believe that it is a clear violation of their privacy and will go out of their way to prevent companies from tracking their online movements.

Online privacy is a hot topic, especially since the NSA scandal broke in 2013, and with more and more users going online, the opportunities for companies to target them with their ads is only going to increase.

But regardless of your own view on data collection, it is an area of online display advertising that has many challenges to overcome, both from the business side and from the user side.

Online Ads And Their Common Pitfalls Of The User Experience

Apart from the privacy concerns users have about online ads, many also feel the user experience is disrupted by ads.

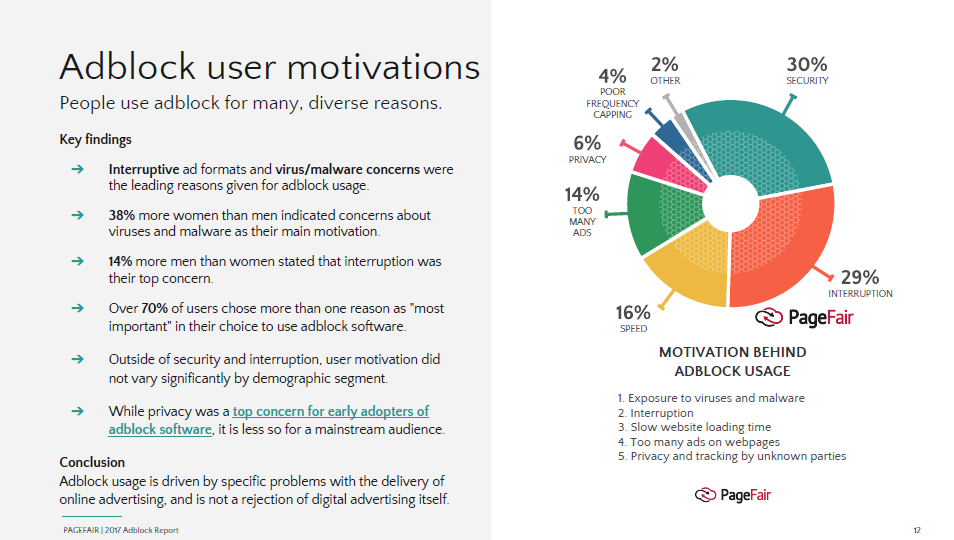

A 2017 report by PageFair uncovered some of the reasons why online users implemented ad blocker software.

Below is a detailed explanation of some of the common pitfalls of online ads.

Too Many or Annoying Ads

One of the main reasons why users install ad blockers is because they are shown too many ads, which often has a negative impact on the user experience.

In additional to traditional banner ads, many websites also have pop-up ups, which are considered the most annoying type of ad as they tend to take up the whole page, stop the user from doing what they were doing (e.g. reading an article), and often require the user to click a small cross to close the ad.

Adware

Adware is a form of software that downloads or displays unwanted ads when a user is online, collects marketing data and other information without the user’s knowledge or redirects search requests to certain advertising websites.

Adware that does not notify the user and attains his or her consent is regarded as malicious.

Adware is the name given to programs that are designed to display advertisements on your computer, redirect your search requests to advertising websites, and collect marketing-type data about you – for example, the types of websites that you visit – so that customized adverts can be displayed.

Other than displaying advertisements and collecting data, adware doesn’t generally make its presence known.

Sometimes there will be no signs of the program in your computer’s system and no indication in your program menu that files have been installed on your machine.

There are two main ways in which Adware can get onto your computer:

Via freeware or shareware: Adware can be included within some freeware or shareware programs as a legitimate way of generating advertising revenues that help to fund the development and distribution of the freeware or shareware program.

Infected websites: A visit to an infected website can result in unauthorized installation of adware on your machine. For instance, adware can access your computer via a browser vulnerability and then install trojans. Adware programs that work in this way are often called browser hijackers.

Creepy Ads

Many consumers feel uncomfortable being shown ads that include personalized elements, such as their name.

Also, many don’t like being shown retargeted ads that display a product or service they looked at previously as they feel like they are being followed around the Internet and that ad companies know too much information about them.

The Future of User Privacy in Digital Advertising

With all the advancements in user privacy over the past few years, AdTech companies should be planning for the future by making changes to their tech to make it privacy friendly and compliant with privacy laws, and staying up to date with new announcements around the privacy settings in web browsers (e.g. ITP and Privacy Sandbox).

With all that’s been happening in digital advertising over the past 5 years regarding privacy, it’s clear that the future of digital advertising lies in privacy-friendly tech and processes.

Test your knowledge with our quiz!

Download the PDF version of our AdTech Book

Read and download the PDF and register your interest for the hardcover version.

Download the PDF version of our AdTech Book

Fill in the form to download the PDF and join our AdTech Book email list to receive all future updated versions, including information about the release of the hardcover version.