In the previous chapters of this book, we looked at how advertisers and publishers use AdTech platforms to set up and run campaigns.

In this chapter we’ll take a look at how AdTech platforms collect data so advertisers and publishers can track and view detailed reports about the performance of their campaigns.

Most of the explanations and examples in this chapter illustrate how tracking and reporting works in both a publisher’s and an advertiser’s ad server, but many other platforms like DSPs and SSPs also include these functionalities.

Impression, Click, and Conversion Tracking

Tracking is an important part of an AdTech platform and is the first step in understanding the performance of an ad campaign and measuring key metrics.

Essentially, tracking involves gathering data about an ad campaign.

There are a number of areas that AdTech platforms track, including basic metrics like impressions, clicks and conversions, and others like viewability and ad-exposure time. They can also track metrics from video ads, such as plays, completion rates, and average time played.

Impression Tracking

Impression tracking is quite simply tracking the number of impressions each ad receives.

An impression is counted each time it is displayed to a user.

For example, if a user visits a web page and sees an ad, then reloads the page and sees the exact same ad again, two impressions would be counted.

The most popular method of counting an impression is to serve a 1×1 transparent image that notifies the ad server of an impression. It’s called an impression tracker (or impression pixel).

The ad server returns a pixel in the ad markup to count the impression when the browser renders the ad markup – as opposed to counting it when the ad server selects the ad – and returns the ad markup to the browser.

This way, the ad impression is counted when the browser loads the creative.

Here’s an example of an impression tracker from the Google Ad Manager ad server (formerly DoubleClick For Publishers):

<IMG SRC="https://ad.doubleclick.net/ddm/trackimp/Nxxxx.site-keyname/Byyyyyyy.n;dc_trk_aid={ad_id};dc_trk_cid={creative_id};ord=[timestamp];dc_lat=N;dc_rdid=Czzzz;tag_for_child_directed_treatment=I?" BORDER="0" HEIGHT="1" WIDTH="1" ALT="Advertisement">The ad server can include a number of additional pixels in the ad markup from third-party AdTech platforms in order to count the impression in multiple systems – e.g. a third-party ad server used only for measurement or an ad-verification platform.

This process of loading other tags or pixels making calls to other platforms is known as piggybacking.

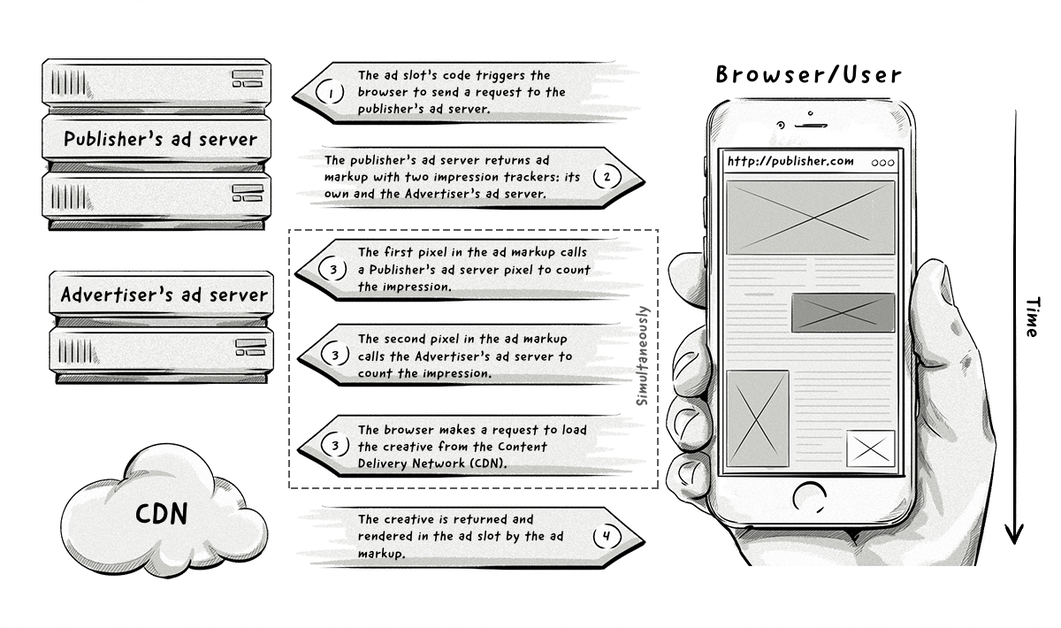

There are two main methods of counting an impression in both the publisher’s and advertiser’s ad servers:

Method 1

The publisher’s ad server includes two 1×1 pixels in the ad markup.

The first pixel sends a request to the publisher’s ad server, which counts the impression, and the second pixel sends a request to the advertiser’s ad server, which also counts the impression.

Both pixels are sent to their respective ad servers at the same time.

Method 2

Both the publisher’s and the advertiser’s ad servers count the impression only when their respective ad servers have received a request for an ad.

Click Tracking

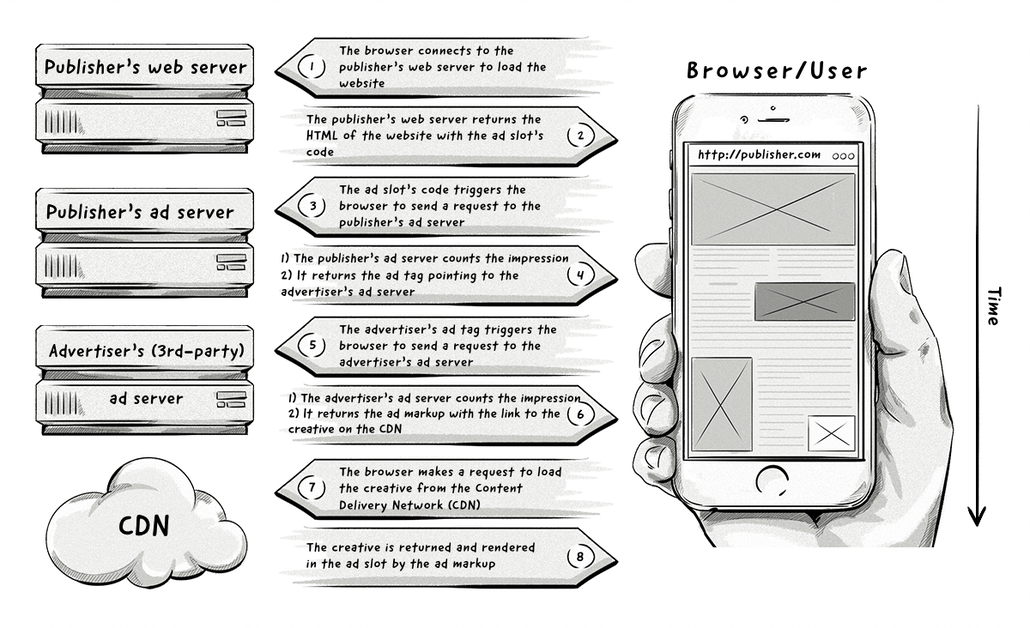

Tracking the number of clicks an ad receives is typically done via a click tracker.

A click tracker is the URL of the ad server’s redirect service, which counts the click and redirects the visitor to the final landing page of the campaign.

The ad server returns the click tracker in the ad markup in order to count the click before the visitor is redirected to the final landing page.

Below is an example of a click tracker from the Google Ad Manager ad server:

http://pubads.g.doubleclick.net/gampad/clk?id=123456789&iu=/1234/adunit&t=page%3DsportsHere’s the basic flow of how a click tracker works:

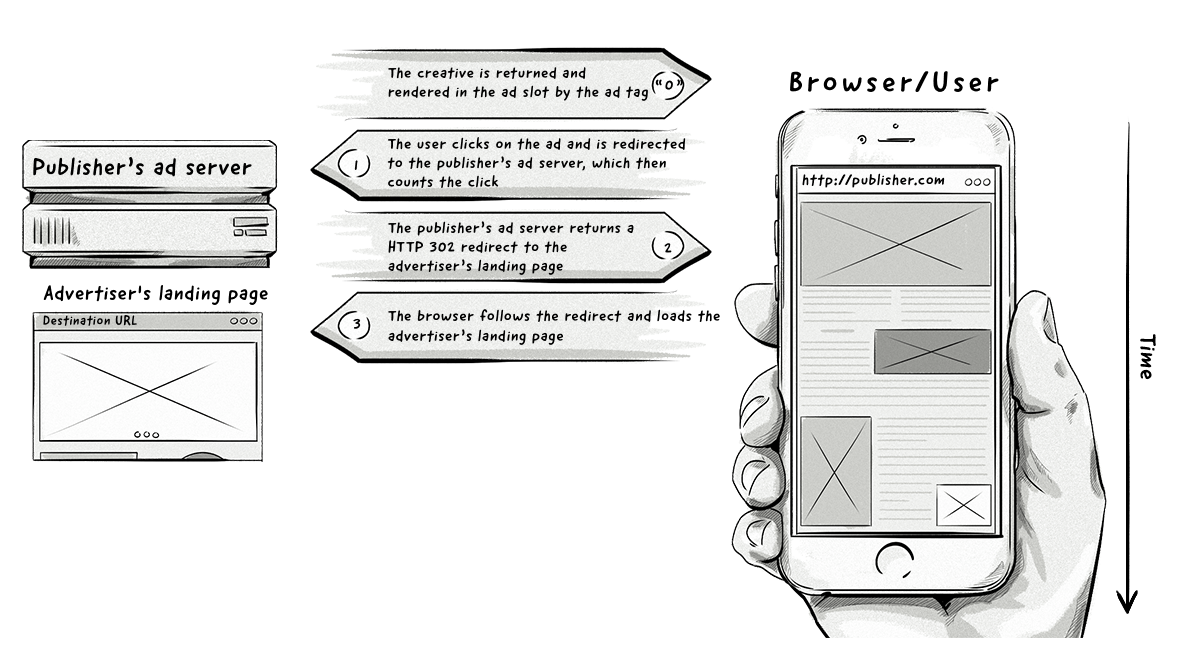

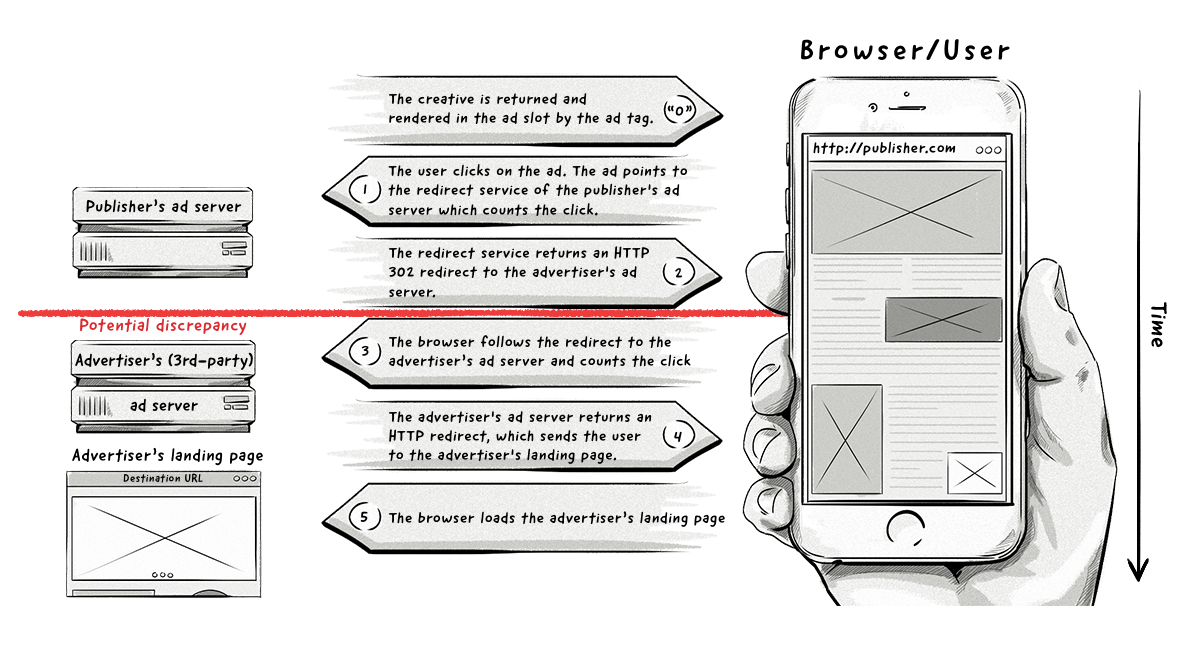

The diagram above illustrates how click tracking works with a publisher’s ad server, but what if the advertiser wants to track the click as well?

To achieve this, they would need to add a click redirect from the publisher’s ad server to the advertiser’s ad server, then redirect the user to the landing page.

The reason why the advertiser’s ad server would also count the same click and impression is to verify the reports provided by the publisher by comparing the number of impressions and clicks, as well as to aggregate all campaign data in one system (i.e. the advertiser’s ad server).

It is possible to add a lot more redirects to conduct more processes, such as:

- Ad verification to detect viewable impressions, bots, and fraudulent activity.

- Tracking clicks in middlemen systems, such as ad networks.

Click URL Macros

Click trackers can support passing the destination URL as a parameter (e.g. redir_url=). This functionality is necessary to add multiple click trackers in the redirect chain and pass the URL of the next redirect dynamically to the click tracker.

Typically, when we paste a click tracker in the ad server, we can use the click URL macro to expand the URL of the next click tracker in the chain.

Here’s an example:

https://ad.example.org/click?ad_id=123456&redir_url=%%click_url%%The ad server automatically expands the %%CLICK_URL%% placeholder to the next click tracker in the chain (i.e. its own click tracker). For example:

https://ad.example.org/click?ad_id=123456&redir_url=http://ad.doubleclick.net/clk%3B246885467%3B71938114%3Bx%3BConversion Tracking

A conversion is registered every time a user completes a goal set by an advertiser or marketer.

A goal could be to get consumers to purchase a product, download a file, or even fill in a contact form on a landing page. Each time a consumer completes one of these actions, a conversion will be recorded.

In online advertising and marketing, conversion tracking is used to report on campaign performance. Also, it is used in conjunction with the cost-per-action (CPA) model where publishers and affiliate advertisers/marketers only receive payment once a conversion is registered.

There are two main types of conversions: click-through conversion and view-through conversion.

Click-through is when a user has clicked on an ad AND converted.

To calculate the click-through conversion (CTC) rate, you divide the number of conversions by the number of clicks that ad received.

CTC % = (conversions ÷ clicks) x 100

View-through is when a user has seen an ad AND didn’t click it BUT converted.

For example, if they saw an ad for a pair of shoes, but instead of clicking on the ad and purchasing them, they went to the website directly and purchased them.

To calculate the view-through conversion (VTC) rate, you divide the number of conversions by the number of impressions the ad received.

VTC % = (conversions ÷ impressions) x 100

The CTC and VTC rates will vary widely from one advertiser to another, as there are a number of factors at play, such as the product or service the advertiser is promoting and the audience exposed to the ads.

What is an attribution window?

With both conversion models, there is something called an attribution window, which refers to the time between when a user first saw or clicked on the ad and the time they actually converted.

The attribution window varies between advertisers, but it can be anywhere from 24 hours to 30 days.

Finding the right attribution-window time frame can be tricky because the longer an attribution window is, the less accurate the attribution becomes.

It can be difficult to know whether a user converted because they saw an ad 30 days before the conversion or because they were persuaded to convert via some other advertising channel.

Similarly, if the attribution window is too short, it could exclude some users who were exposed to the ad and converted as a result of seeing the ad. This not only affects the advertiser’s attribution reports, but also impacts the publisher’s potential revenue.

The advantages and disadvantages of these two types of conversions are as follows:

| Click-through conversions | View-through conversions | |

|---|---|---|

| Advantages |

Allows advertisers to accurately attribute the clicks to conversions, leaving little or no room for inaccurate reporting. |

Depending on the product or service being promoted, this type of conversion can work better for middle- and top-funnel campaigns than for click-through conversions. |

| Disadvantages |

One of the main disadvantages of this method has more to do with the attribution model than the click-through conversion itself. For example, if you use the first or last click-attribution model, it can be hard to know if that click was the event that actually influenced the user to convert. |

It’s possible that the ad was displayed to the user, but they may not have actually seen it (the ad might not have been in the viewport of the browser) or been influenced by it. In other words, it’s possible to attribute too many conversions to the campaign. Conversion attribution may be lost if a visitor deletes their cookies in the time between seeing the ad and converting. This method is also more prone to fraud. For example, it’s possible that the pixel could be fired without the actual creative being shown. Then, if the user coverts, it will be recorded as a view-through conversion, despite the user never actually seeing the ad. |

These two types of conversions are part of a larger and broader field of online advertising and marketing known as attribution, which takes into account a number of different interactions a visitor has with a brand or ad.

Apart from there being different types of conversions, there are also different conversion-tracking methods:

The Pixel Method

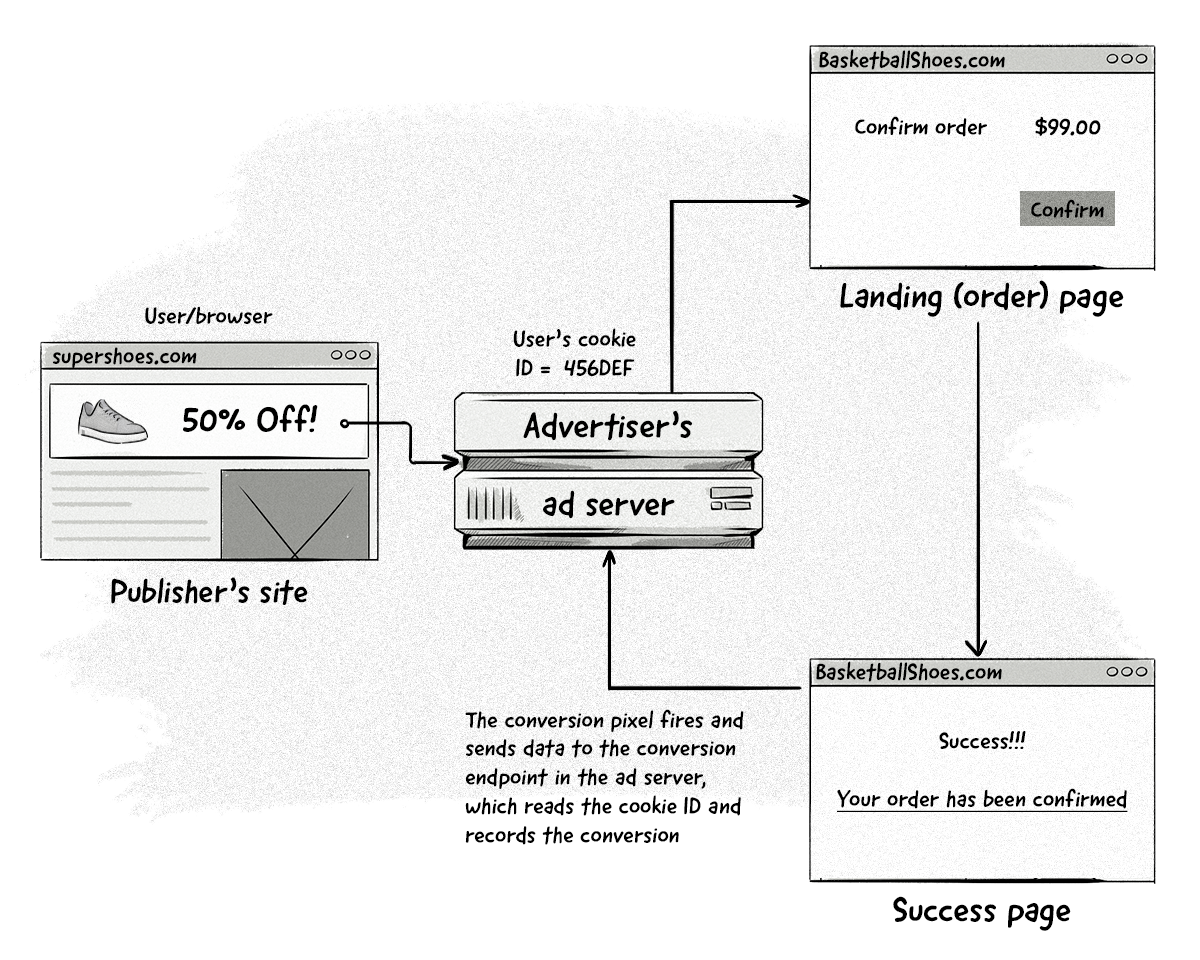

The pixel method for click-through tracking works like this:

In the pixel method for click-through conversions, the user visits a website, sees an ad and clicks on it. They are then taken to the advertiser’s landing page and convert. When the user clicks on the ad, the advertiser’s conversion pixel fires and records the user’s cookie ID in the advertiser’s ad server.

Typically, an ad server will assume that the last click ID for the particular cookie ID generated the conversion.

This way, the conversion can be associated with a specific ad, line item, and campaign (the click ID will store information about which ad the user clicked).

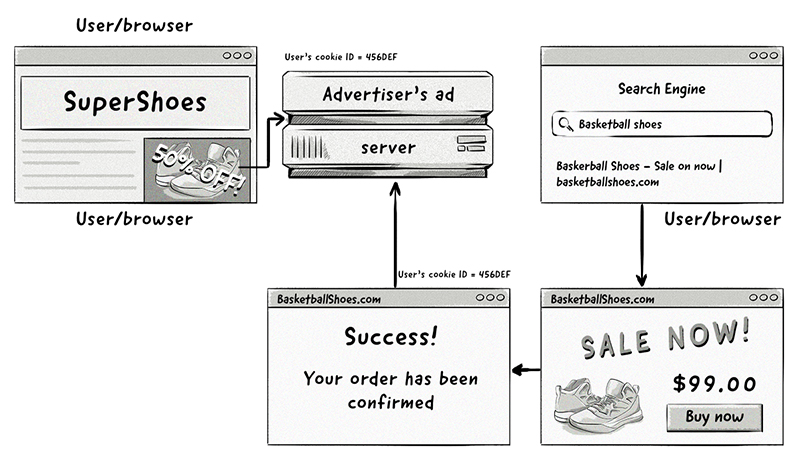

The pixel method for view-through tracking:

In the pixel method for view-through conversions, the user sees an ad (but doesn’t click on it), leaves the publisher’s website, comes back to the advertiser’s website through another channel (e.g. via a Google search), and then converts.

The advertiser is able to attribute the conversion to the ad that was on the publisher’s website by comparing the cookie ID it created when it displayed the ad on the publisher’s site with the one created when the conversion pixel fired on the success page.

The Server-Side Method

The server-side method works in a similar way to the pixel method; however, instead of firing a pixel and passing the user’s cookie ID to the ad server, the user’s cookie ID is passed from the page to the ad server via a server-to-server call.

This method is widely used in the affiliate advertising and marketing space because it is so crucial to get the data right and reliably track the conversions for the partners (i.e. publishers) because they get paid only for conversions.

Below are a couple examples to help explain the server-side method:

Example 1: Selling insurance as an affiliate

Affiliate advertisers and marketers are paid on a cost-per-action/acquisition (CPA) basis, which means they only receive payment, either in the form of a fixed-priced commission or a percentage of the sale’s total value, when a user converts.

However, it could be hours, days or even weeks between the time a user sees the insurance ad on the publisher’s site and the time they actually convert (purchase the insurance policy).

Therefore, the system on the advertiser’s side must track the click ID and notify the affiliate ad network (or the ad server) about the successful conversion once the conversion is verified – e.g. when the application is processed successfully or when payment from the user is received.

Example 2: App installs

Attributing a conversion for an app install to a publisher or affiliate advertiser/marketer is different than attributing conversions in browsers. The reason for this is because, unlike web and mobile browsers that are able to fire pixels, there is no way to fire a pixel in a mobile app.

In order to track events such as conversions, the software-development kit (SDK) in the app has to notify the ad server of the installation, which is then attributed to the app-store redirect generated by the partner (i.e. publisher or affiliate).

A postback notification is sent to notify the publisher or affiliate about the successful install, meaning they have just earned a CPA commission.

The Importance of Properly Attributing Affiliate Campaigns

As you can probably imagine, trust is an issue that often arises with CPA campaigns.

There are a few ways advertisers can evade paying commissions to publishers and affiliates, but this ultimately disadvantages the advertiser as well as the publisher or affiliate.

Let us explain.

In the affiliate, CPA, and revenue-sharing space, publishers can ultimately choose from hundreds of offers to promote.

The publisher’s and affiliate’s goal is to make the most money possible from the offers they promote, so most of them will test the offers on a small percentage of their traffic and tweak them to find the ones that generate the most revenue.

If the offers don’t perform well, which could be due to a number of reasons (such as offers not being the right fit for their audience), they will simply remove them from their site and stop promoting them, which means the advertiser won’t receive any conversions from the offers.

This essentially defeats the point of the whole process.

Reporting

The reporting function of an AdTech platform is responsible for displaying metrics about many different areas of a campaign.

The reports are highly valuable for both advertisers and publishers, as they provide clear insights into the performance of their campaigns and the users who click on their ads.

For every impression served, an AdTech platform stores a record with the following attributes:

- Timestamp (impression, click, conversion)

- IP address

- Campaign ID

- Line item ID

- Ad/creative ID

- Geolocation

- Browser

- OS

- Publisher domain

- Publisher placement

- … and others

Similar information is stored for every click and conversion.

Metrics

A metric is an actual number calculated for the overall campaign or the data matching the specific dimension’s value.

Some metrics can be derived from others; for example, calculating the CTR metric is done by dividing the total number of clicks (metric) by the total number of impressions (metric):

CTR = clicks / impressions x 100.

Examples of metrics include:

- Impressions: the number of times an ad was displayed.

- Clicks: The number of times an ad was clicked on.

- Conversions: the number of desired actions (goals) performed by a user (e.g. filling in a contact form or making a purchase).

- Reach: the number of unique visitors/devices that the campaign reached.

- Click-through rate (CTR): number of clicks / number of impressions x 100.

- Cost per mille (CPM): cost per 1,000 impressions.

- Cost per click (CPC): the cost of each click an ad or link generates.

- Cost per action/acquisition (CPA): the cost of each action, acquisition, or conversion. CPA is often used in affiliate marketing.

- Conversion rate (CVR): the number of conversions divided by the number of clicks (then multiplied by 100 to get a percentage). This model is typically used for click-through conversions.

- Amount spent (cost): the amount of money spent for the respective impressions, clicks and conversions.

- Revenue (total conversion value): the amount of money earned from the conversions.

Effective Cost Per Mille, Click, and Action (eCPM, eCPC, eCPA)

In most reports, you’ll see metrics that have the letter e before them.

The e stands for effective and is used to determine the revenue generated by a particular pricing model (e.g. eCPM).

Effective CPM, CPC, and CPA can be calculated for any campaign and can be worked out by using the following formulas:

Effective cost per click (eCPC) = budget spend / number of clicks

Effective cost per action/acquisition (eCPA) = budget spend / number of conversions

Effective cost per mille (eCPM) = budget spend / number of impressions x 1000

As advertisers and publishers select a pricing model before the campaign starts, these pricing models show advertisers and publishers what the results would have been if they had used that particular pricing model.

Very often, advertisers will calculate their campaigns in different pricing models to compare their performance.

On the publisher’s side, they may want to calculate the eCPC or eCPA for all their CPM campaigns to see if they could have made more revenue via those pricing models.

For example, let’s have a look at the following three campaigns:

Campaign #1: CPM

| Campaign | Impressions | Clicks | Conversions | Total cost | CPM | eCPC | eCPA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Summer promotion | 1,000,000 | 1,500 | 10 | $4,000 | $4 | $2.67 | $400 |

Campaign #2: CPC

| Campaign | Impressions | Clicks | Conversions | Total cost | eCPM | CPC | eCPA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Summer promotion 2 | 1,000,000 | 2,000 | 50 | $10,000 | $10 | $5 | $200 |

Campaign #3: CPA

| Campaign | Impressions | Clicks | Conversions | Total cost | eCPM | eCPC | CPA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Summer promotion 3 | 1,000,000 | 2,500 | 80 | $15,000 | $15 | $6 | $187.50 |

The table above shows the eCPM, eCPC and eCPA for the three campaigns.

In performance-based advertising, advertisers will look at the return on investment (ROI) of the campaign and traffic source. This metric is used to evaluate the efficiency of their advertising budget.

It is calculated in the following way:

ROI = (total conversion value – amount spent) / amount spent x 100%

The ROI metric will have positive values when the advertiser is making money and negative values when the advertiser is losing money.

Example:

| Campaign | Total conversion value | Amount spent | ROI | Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Campaign 1 | $1,200 | $1,000 | +20% | For every dollar spent, we earn 20 cents* |

| Campaign 2 | $900 | $1,000 | -10% | For every dollar spent, we lose 10 cents* |

*This does not take into account any fixed or variable costs that you may have with delivering goods or services to the end customers, so even a 20% ROI may not necessarily mean that you make profit—however, this works very well with digital goods where your marginal cost is very low.

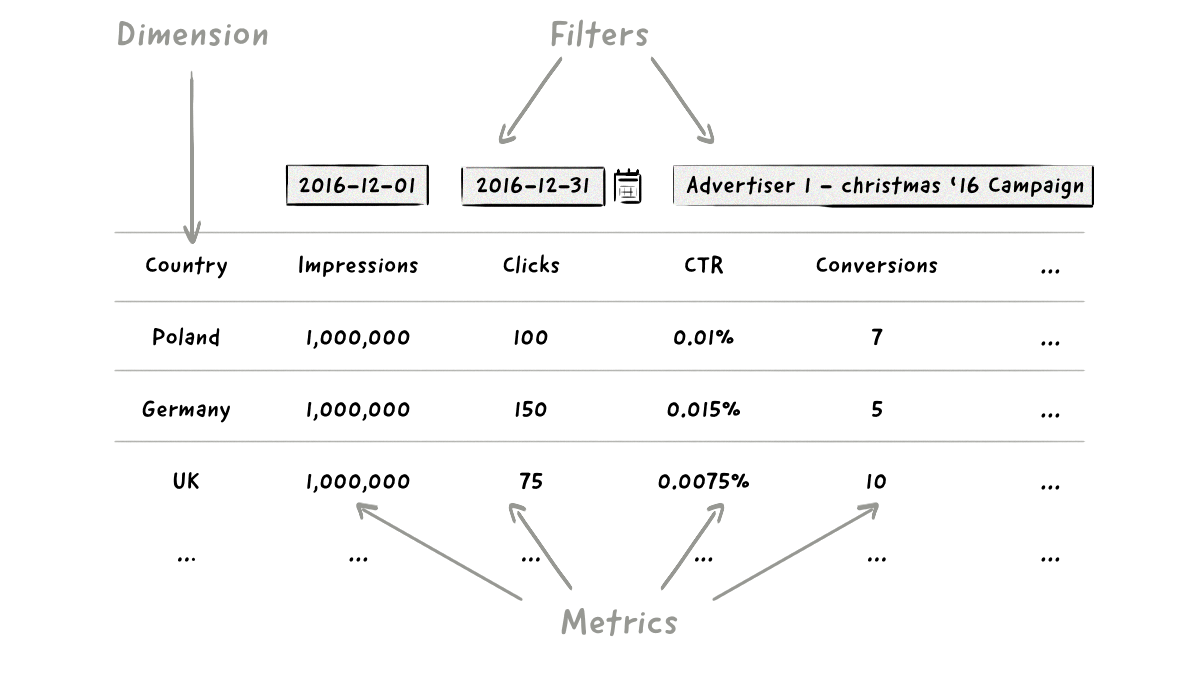

Dimension and Subdimensions

A dimension is an attribute or variable of data used to break down a report.

Some examples of dimensions include:

- Country

- Device type

- Browser type

- Hour of the day

- Campaign

- Line item

- Creative

- Date, day of the week

- Publisher URL/domain

- OS and OS version

- Geolocation

Subdimensions (aka drill-downs) allow us to view data from a given dimension that’s broken down by another dimension (e.g. Country -> Carrier -> Line item -> Ad).

Filtering

Filtering (aka segmentation) allows you to restrict the data set that you are running the report on.

Common filters include:

- Date range

- Advertiser -> Insertion Order -> Line Item -> Ad

On top of that, you can typically apply an include/exclude filter for any value for any dimension, e.g.:

- Country = Poland OR Germany OR United Kingdom

- Device type = Tablet

- Day of week = Monday-Friday

Technical Considerations of Reporting

From an ad-operations perspective, there are some important aspects of reporting that need to be acknowledged, otherwise the advertiser or publisher could be confused and misled when comparing data from other systems.

Delays

There is usually a delay between the time an event is received by the system and the time it’s included in the reports. Most of the time, it is a few minutes, but sometimes, it can be as high as a couple of hours.

The most recent data is often an approximation of a complete report, and an accurate report is available after some time. It’s best to check these values for the reporting system that you are using.

An example of a data delay:

Report-data approximation is available within 15 minutes of an event occurrence, with an accurate report available within a maximum of 24 hours. Typically, the accurate report should be used for billing purposes.

Reporting Time Zone

When comparing reports from different systems, it is important to determine whether they are both using the same time zone and that only accurate data is used (not an approximation).

Data Retention

Some reporting systems handle the increase in data by dropping events older than some threshold age (e.g. six months or one year). An alternative space and cost-saving technique is to decrease report granularity with time.

For example, data from the last month is available with precision up to an hour, data from one month to one year is summed up for the entire day, and data older than one year is only available in the form of campaign totals.

Discrepancies: Trust, But Verify

In online advertising, a discrepancy is the difference between reported data in two different AdTech platforms – e.g. between a publisher’s ad server and an advertiser’s ad server.

It is a very sensitive topic because the data collected by these AdTech platforms is later used for billing purposes and is often subject of disputes between publishers, advertisers, and AdTech vendors.

While there can be a number of reasons for discrepancies, most can be attributed to technical errors.

A majority of AdTech platforms depend on client-side tracking methods – i.e. those carried out in web browsers, SDKs in mobile apps, and other embedded devices – for receiving data about events, such as impressions, clicks, and conversions.

The issue with client-side tracking is that it is error prone (more on the causes below).

In this section, we’ll answer the following questions:

- How can one verify whether a publisher’s ad server or an advertiser’s ad server reports are valid?

- Why are discrepancies inevitable?

- What are the common causes of discrepancies?

- What is the acceptable level of discrepancies?

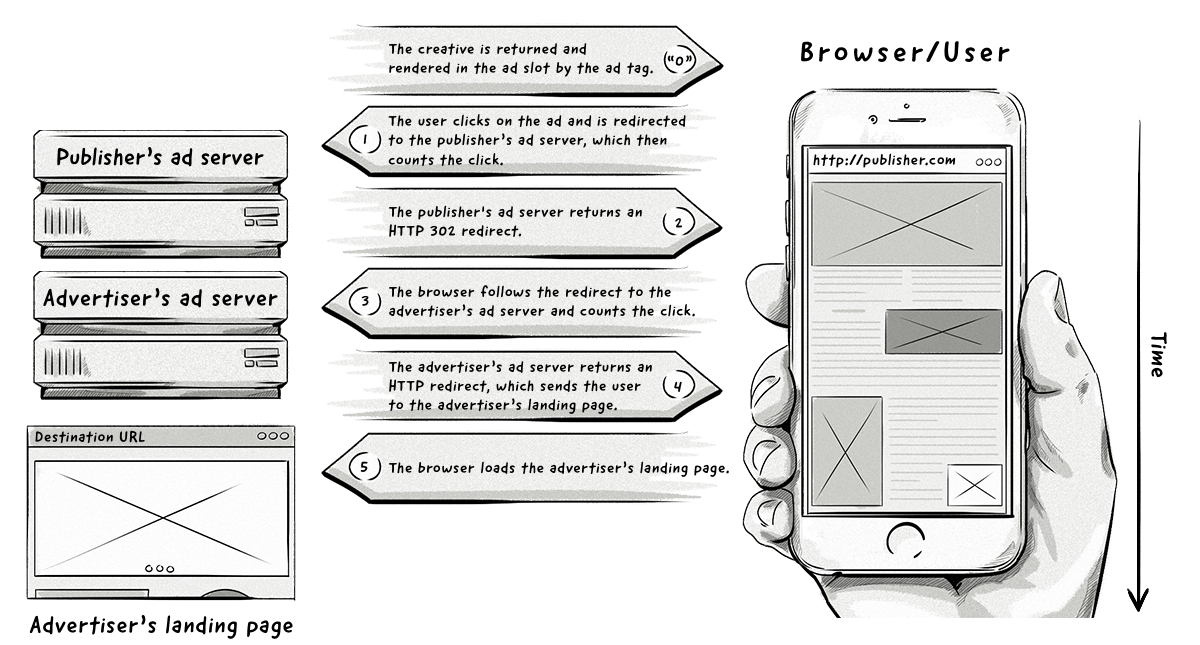

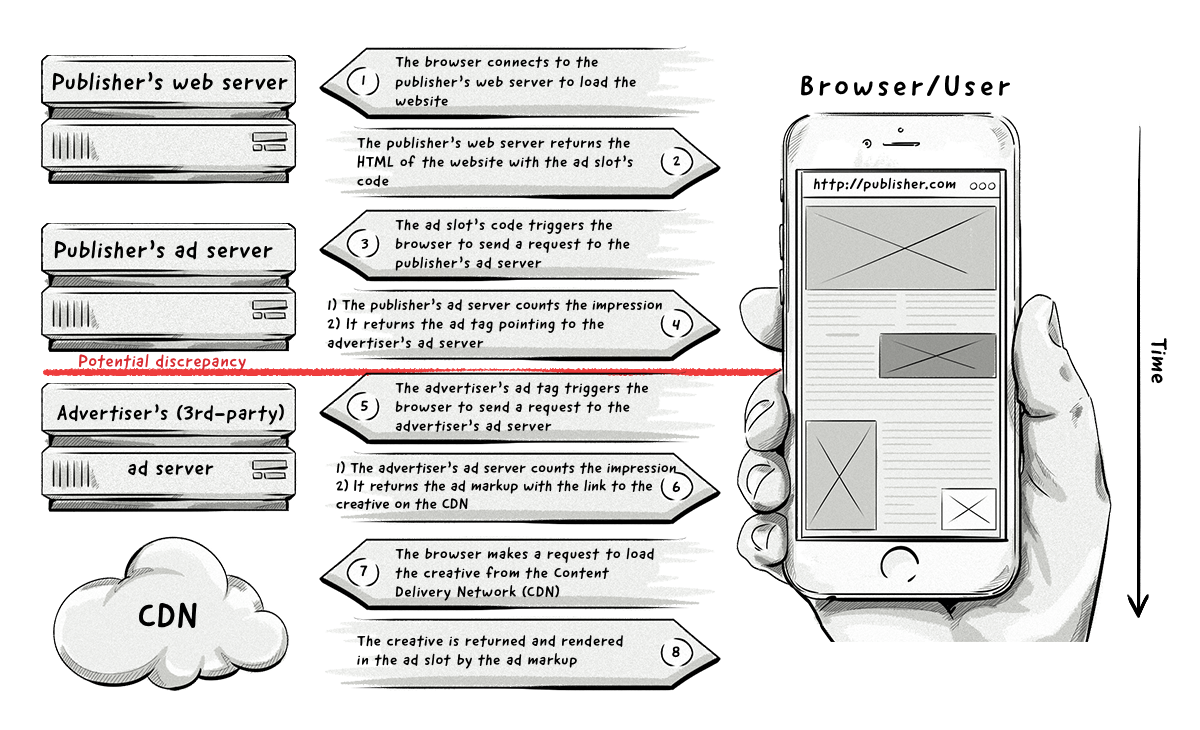

Below are two images that illustrate some situations when discrepancies are likely to occur:

1. During impression tracking:

The publisher’s ad tag loads and the ad impression is tracked, but for whatever reason, the browser didn’t load the advertiser’s ad tag or impression pixel.

2. When counting the click:

A discrepancy could occur if the redirect chain is broken, which would mean that the advertiser’s ad server wouldn’t receive information about the click and the user wouldn’t be taken to the final landing page.

As we can see in the above diagrams, most discrepancies will occur after the publisher’s ad server has loaded the ad tag, meaning advertisers will often report lower numbers than publishers.

Discrepancies and Common Causes

Below are some possible reasons as to why discrepancies occur.

Human and Implementation Errors

AdOps are usually swamped with a lot of ad trafficking and last-minute entries. It’s not uncommon for agencies to send or change tags at the last minute before the campaign goes live.

Add to this the manual work that must be performed for each of the campaigns, and it’s easy to make a mistake, especially by a junior or overloaded AdOps team member.

Specifically, common errors are:

Pasting an incomplete impression-tracking pixel that’s missing the full ID: Launching an incorrect pixel will result in hitting the advertiser’s ad server, but not tracking the impression due to the missing ad or campaign identifier.

Using the incorrect impression pixel: For example, pasting an impression pixel from Campaign ABC to Campaign 123 that was kept in the pastebin.

Implementing the wrong macro: Failing to add a cache buster may cause the pixel to be cached by the browser and therefore won’t correctly report impressions for subsequent ad views of the same user/browser.

Difference in run dates or failure to fully set up the campaign on one of the ad servers: The campaign may have already started in one ad server, but may not be running in the other ad server, which would cause the campaign to not display ads.

For example, if the tags weren’t properly set up in the advertiser’s ad server, but were set up correctly in the publisher’s, then the publisher’s tags would run properly on their site and track every impression of the empty ad.

Configuration Issues

Discrepancies in reporting can also be caused by differences in the reporting configuration between different AdTech platforms, such as:

Time zone: If one AdTech platform records events in Central Time (CT) and another one in Pacific Time (PT), then you’ll notice disprecencies when looking at time-based dimensions (e.g. daily and hourly reports).

Traffic validation and filtering: Some AdTech platforms use traffic validation and filtering services in an attempt to block fraudulent traffic, which can also cause discrepancies between platforms.

Differences in terminology and counting methodology: While most AdTech platforms can agree on the proper definition of common metrics like impressions, clicks, and conversions, there can be some differences in how these are counted.

For example, one AdTech platform could count impressions when the pixel fires in the browser, whereas another could count impressions when the ad is served (i.e. when it leaves the server). In the latter case, an impression would be counted when it is served, but it might not actually load in the browser due to technical issues.

Client-Side Issues

As we mentioned above, most AdTech platforms rely on client-side tracking for reporting, but often encounter a number of technical issues, such as:

- Poor Internet connectivity and latency.

- JavaScript errors could be breaking the execution of the ad code.

- The browser could be set to disable JavaScript or use extensions like <noscript>.

- The URL’s maximum length could have been reached, meaning some redirect paths could be cut off and not executed.

- Special characters passed in the URL might not be parsed correctly by the AdTech platform.

- The creative’s file size could be too big or might not comply with the IAB’s standards.

- The webpage could contain large files (e.g. rich images that take a long time to load), which increases overall latency.

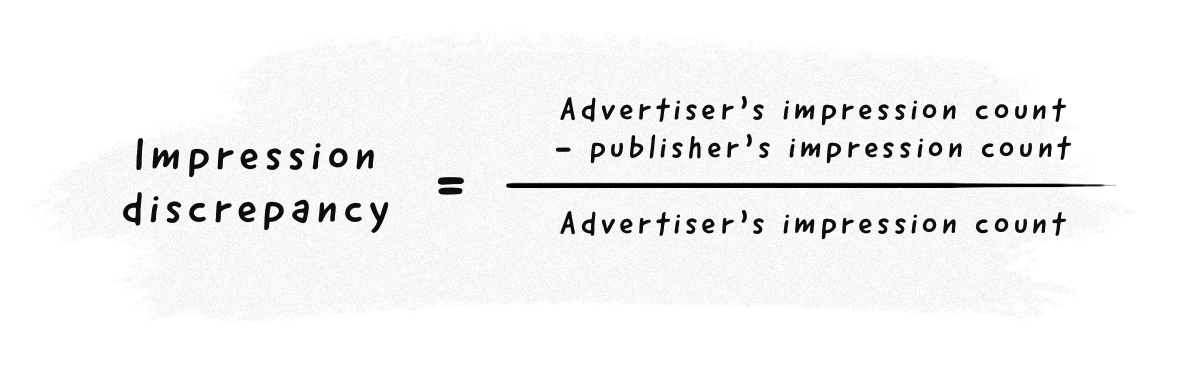

How to Calculate an Impression Discrepancy

Calculating a discrepancy between two AdTech platforms can be done via the following formula:

Impression discrepancy = (publisher’s impression count – advertiser’s impression count) / advertiser’s impression count

To work out the percentage, simply multiply the final number by 100.

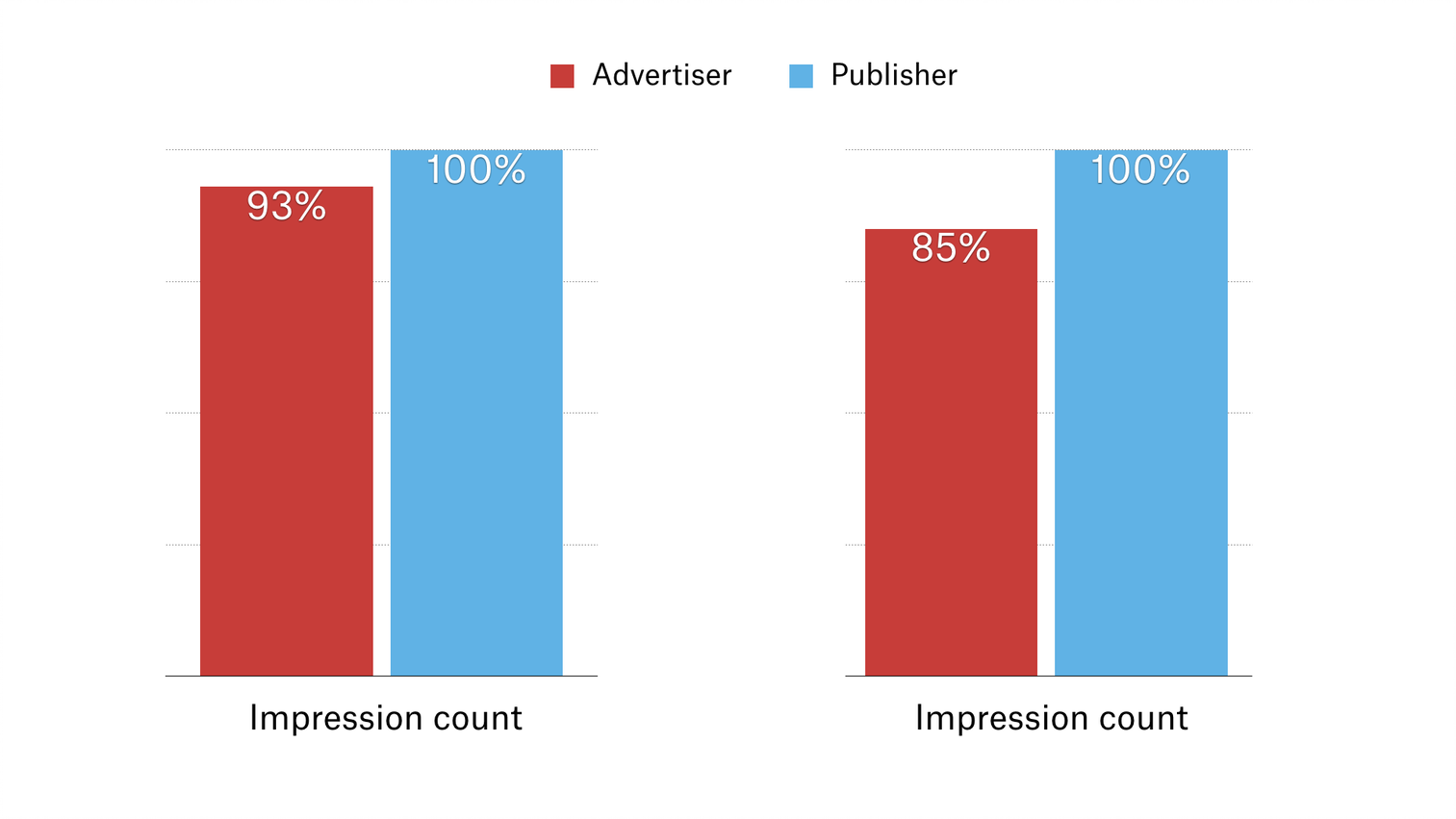

Discrepancy Tolerance

The IAB states that a tolerance of 10% discrepancy based on the publisher’s figures is acceptable.

The example on the right represents a discrepancy of 15%, which is outside the acceptable range.

A discrepancy is calculated from the advertiser’s numbers, but if it’s less than 10%, then the publisher’s metric is typically used for billing.

Reconciliation

Reconciliation is a process used to compare two sets of records to ensure the figures are in agreement and are accurate.

Due to the wide-ranging number of possible reasons for discrepancies, most of the time reconciliation is a manual process whereby AdOps team members log in to their AdTech platform accounts, compile reports, download the data, and look at where the main problems lie.

Chapter Summary

- The most popular method of counting an impression is to serve a 1×1 transparent image that notifies the ad server of an impression, known as an impression tracker (or impression pixel).

- When the impression tracker loads, it records an impression in the AdTech platform.

- Tracking the number of clicks an ad receives is typically done via a click tracker, which is the URL of the ad server’s redirect service that counts the click and redirects the visitor to the final landing page of the campaign.

- A conversion is registered every time a user completes a goal set by an advertiser or marketer, which could be a purchase or a download.

- There are two main types of conversion tracking: click-through conversion and view-through conversion, which can either be recorded by firing a pixel on the confirmation page or by tracking the conversions server-side.

- The reporting function of an AdTech platform is responsible for displaying metrics, dimensions, and subdimensions about many different areas of a campaign.

- Discrepancies, which are the difference between the reported numbers of two different AdTech platforms, are common in AdTech and there can be many reasons why they occur. Common reasons are related to human error, reporting configuration, and technical issues.

- The IAB states that a discrepancy of under 10% is acceptable.

Test your knowledge with our quiz!

Download the PDF version of our AdTech Book

Read and download the PDF and register your interest for the hardcover version — coming in 2023!

Download the PDF version of our AdTech Book

Fill in the form to download the PDF and join our AdTech Book email list to receive all future updated versions.