Earlier in the book, we looked at how AdTech platforms use various targeting methods to display ads to the right audience, but how do they know whether a person on a given website or mobile app is part of their target audience?

The answer: via user identification methods.

Why Do We Need to Identify Users?

- To power behavioral targeting and content personalization.

- To run retargeting/remarketing campaigns.

- To measure the reach of campaigns.

- To track conversions.

- To attribute sales and conversions to impressions and clicks.

- To apply frequency capping.

Different User-Identification Methods

The process of identifying users depends on the type of device they are using (e.g. a smartphone or laptop) and whether they are using a web browser or mobile app.

For example, a user visiting web pages in a web browser, either on a mobile device or computer, would be identified by browser-based identification methods.

A user playing a mobile-app game on a smartphone or tablet would be identified by a mobile identifier.

Let’s take a closer look at these identification methods.

Web Browsers

Web browsers have been around since the beginning of the Internet and allow users to access websites on desktops, laptops and mobile devices.

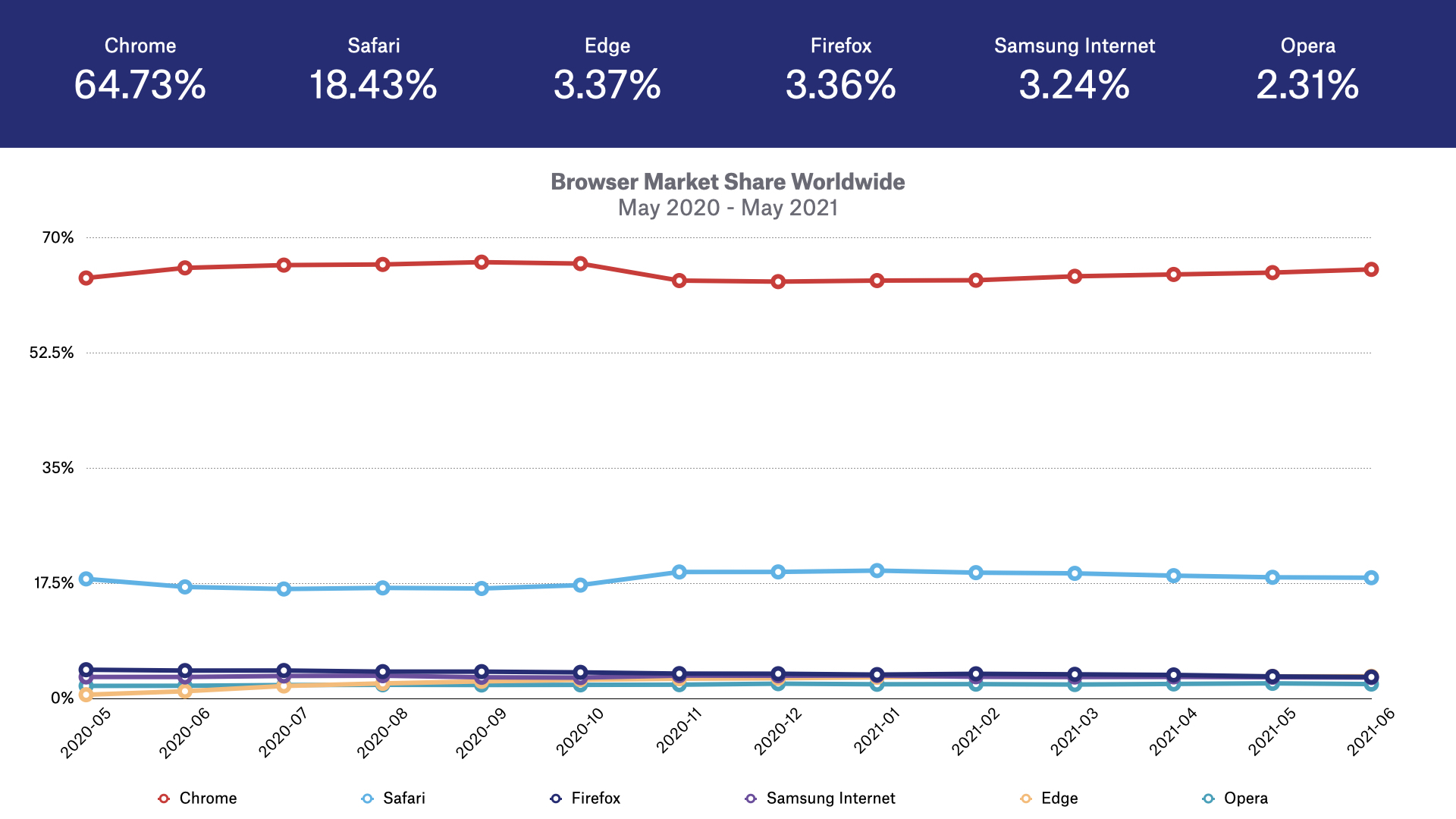

According to statcounter, the most popular web browsers globally based on market share are:

- Google Chrome (64%)

- Apple Safari (18%)

- Mozilla Firefox (3%)

The above illustrates the global market share of the most popular web browsers, but this changes when adding in variables such as country and device.

For example, in Germany, Firefox has 12% market share compared to a 3% global market share.

Similarly, Apple’s Safari web browser is the most popular web browser on iOS-powered devices like iPhones and iPads, and Chrome is the most popular web browser on Android devices.

The main browser-based user-identification methods are cookies, device fingerprints and HTML local storage.

Cookies

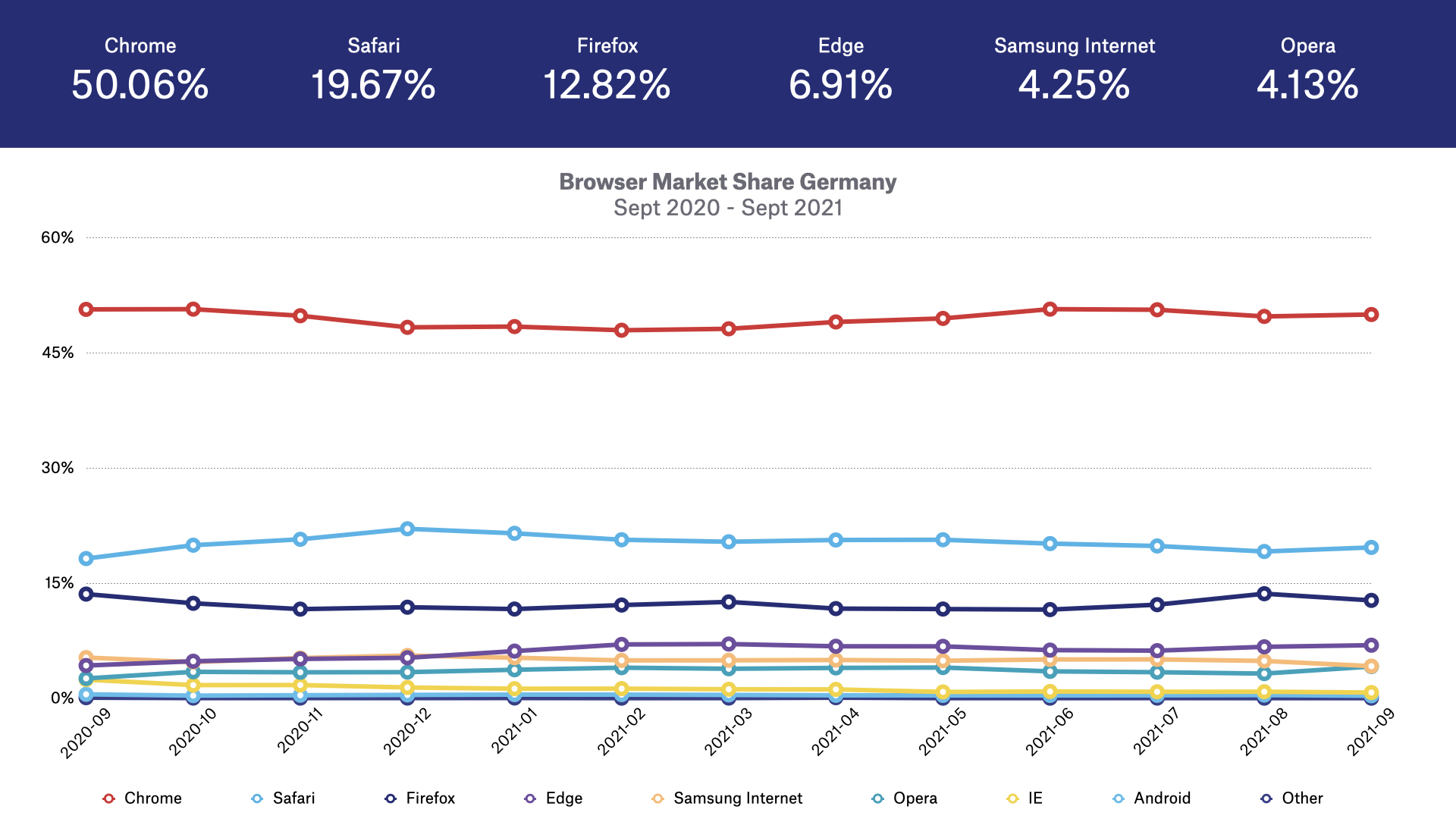

Cookies (aka web cookies, HTML cookies and browser cookies) are small files that are placed on a user’s device by a web server when accessing websites.

Web cookies were created by Lou Montulli in 1994 as a way to remember stateful information in an otherwise stateless environment.

What that means is that the HTTP protocol, which is the main protocol for communication between a web browser and a web server, is a stateless process; it can’t store any data or information, it can only receive requests and respond to them.

Cookies are used to help web browsers store data and information when communicating with web servers via the HTTP protocol.

When a user returns to a website they’ve previously visited, cookies will help the website remember certain things, such as what content the user viewed and which pages they accessed.

Some of the main uses of cookies include:

- Website setup: Cookies can help web browsers remember user preferences, such as language and currency.

- Sign in: To keep users logged in to their accounts, a unique session ID is stored in a cookie so the user won’t have to log in to their account each time they open their browser.

- eCommerce: Cookies used by eCommerce stores help web browsers remember which products users viewed, added to the shopping cart and purchased.

- Analytics: Cookies are used to store a user identifier that collects data about the user’s interaction with the website under one profile and session, such as which pages they visited, what areas they clicked on and if they completed any goals (e.g. downloaded an ebook).

- Behavioral targeting and advertising: AdTech platforms use cookies to identify users and show relevant ads to them based on their previous behavior, such as which websites and pages they’ve visited. Cookies also help advertisers and publishers know which ads they’ve viewed and clicked on.

Cookies have been the most common method for identifying users on web browsers since the early days of the Internet, however, the rise of privacy laws, such as the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and privacy features in browsers (e.g. Safari’s Intelligent Tracking Prevention) are restricting the creation and access to cookies (more on that below).

Different Types of Cookies

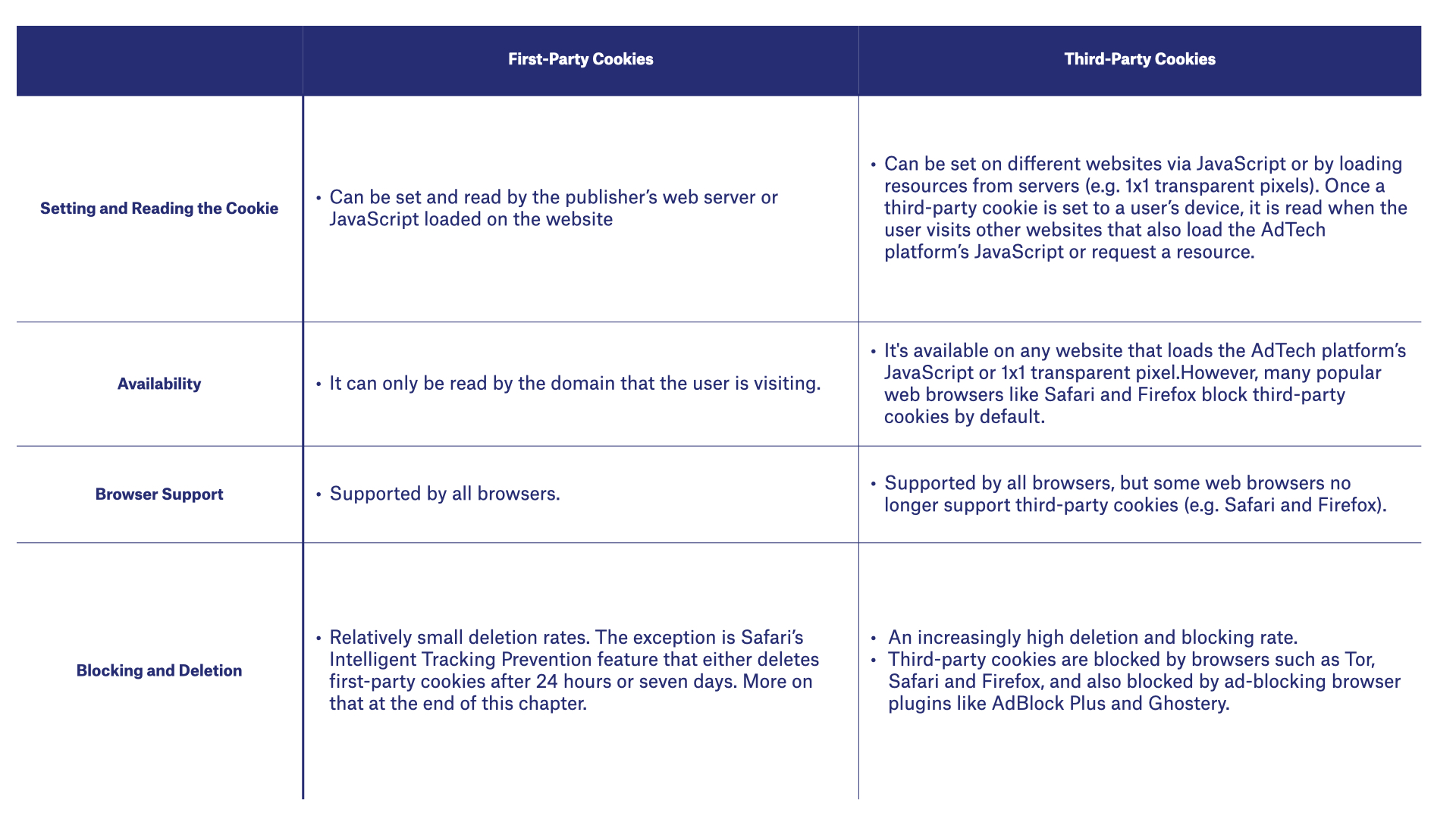

For the most part, all cookies are the same. However, there are two main types of cookies: first-party and third-party cookies.

The difference has to do with the relationship between the website and the server that created them.

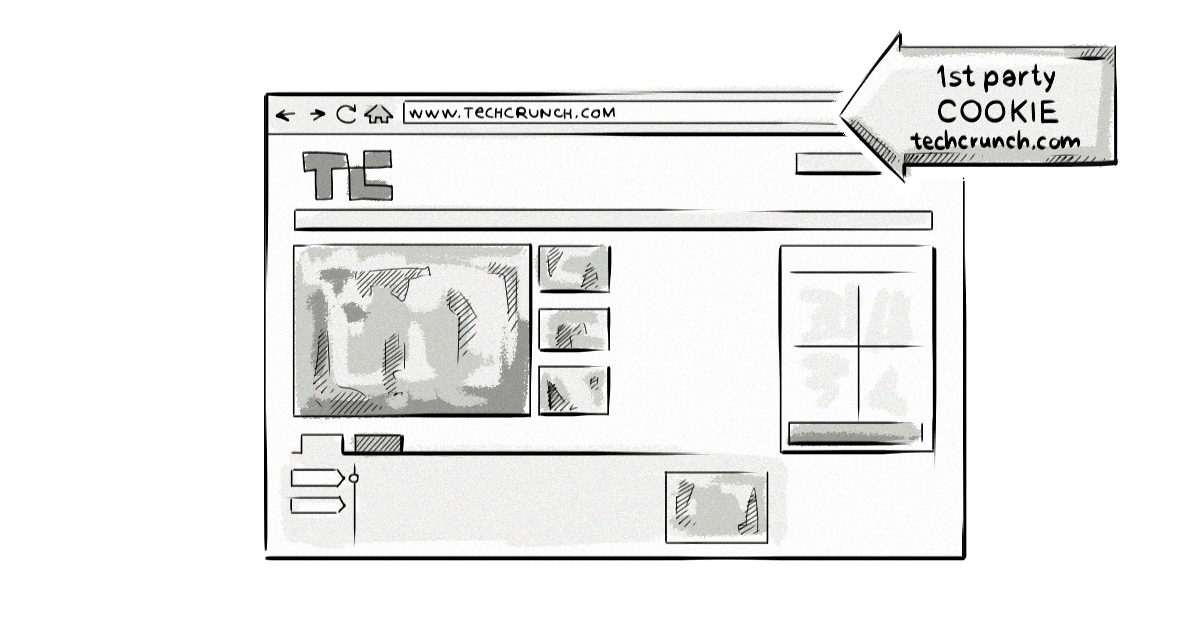

First-party cookies are created by the domain (website) a user visits directly. For example, if you visit techcrunch.com, then it will create some first-party cookies and save them to your device.

First-party cookies are typically used to deliver a good user experience by remembering specific information and user preferences.

For example, first-party cookies help websites remember the language a user has set and which products they’ve added to a shopping cart.

Also, first-party cookies can allow users to stay logged in to websites and accounts, meaning they don’t have to log in each time they visit their favorite websites.

Although they can be used for online advertising, they are limited in their ability to identify users across different domains. This means that a first-party cookie created by ssp1.com on techcrunch.com can’t be read by ssp1.com on different websites.

In order to overcome this limitation, AdTech companies use third-party cookies and cookie syncing to identify users across different websites (more on that below).

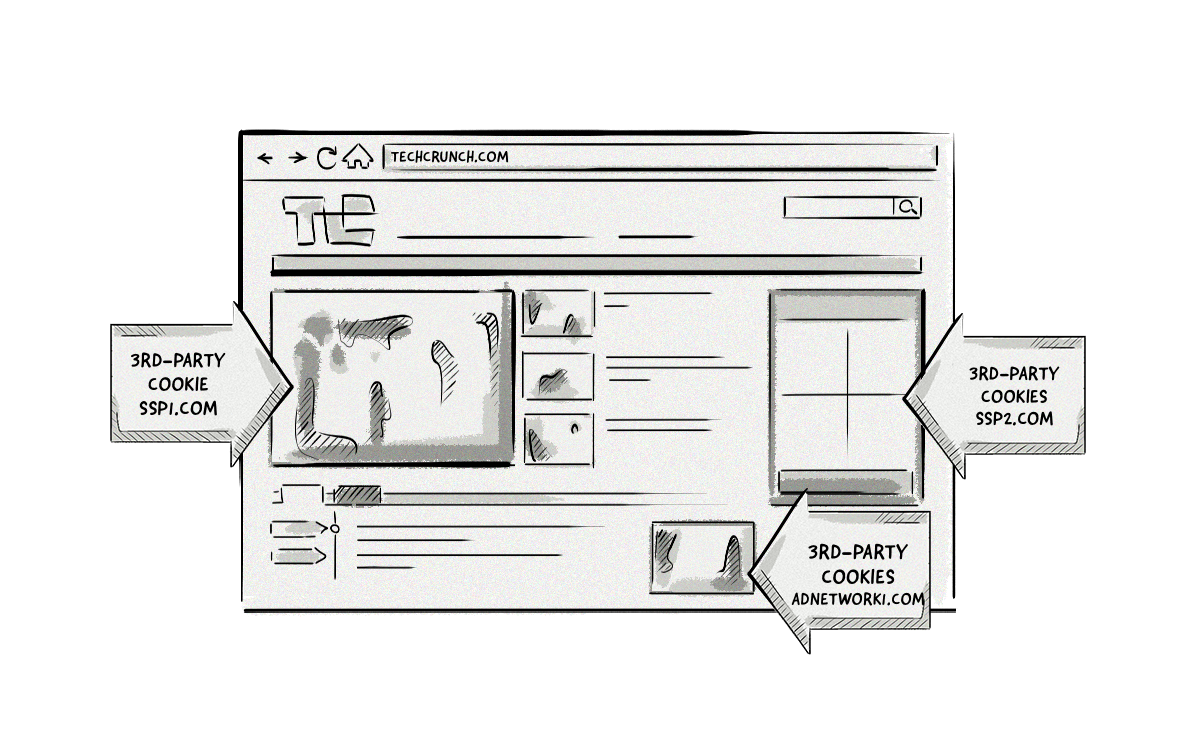

Third-party cookies, also referred to as tracking cookies and third-party trackers, are created by domains other than the one the user is on.

For example, if you visit techcrunch.com and it loads a piece of JavaScript from an AdTech platform (e.g. ssp1.com), a first-party cookie would be created for techcrunch.com and a third-party cookie would be created for ssp1.com.

Because ssp1.com is not the domain the user is visiting, it is classed as a third-party cookie.

All other cookies created by domains other than techcrunch.com would also be classed as third-party cookies.

Third-party cookies have long been the backbone of online advertising, allowing AdTech companies to identify users as they move around the web, run targeted ad campaigns based on a user’s behavior, and attribute impressions, visits, clicks and conversions.

However, third-party cookies are becoming less effective due to privacy laws like the GDPR, privacy features in browsers like Safari’s Intelligent Tracking Prevention and Firefox’s Enhanced Tracking Prevention, and browser plugins like AdBlock Plus and Ghostery.

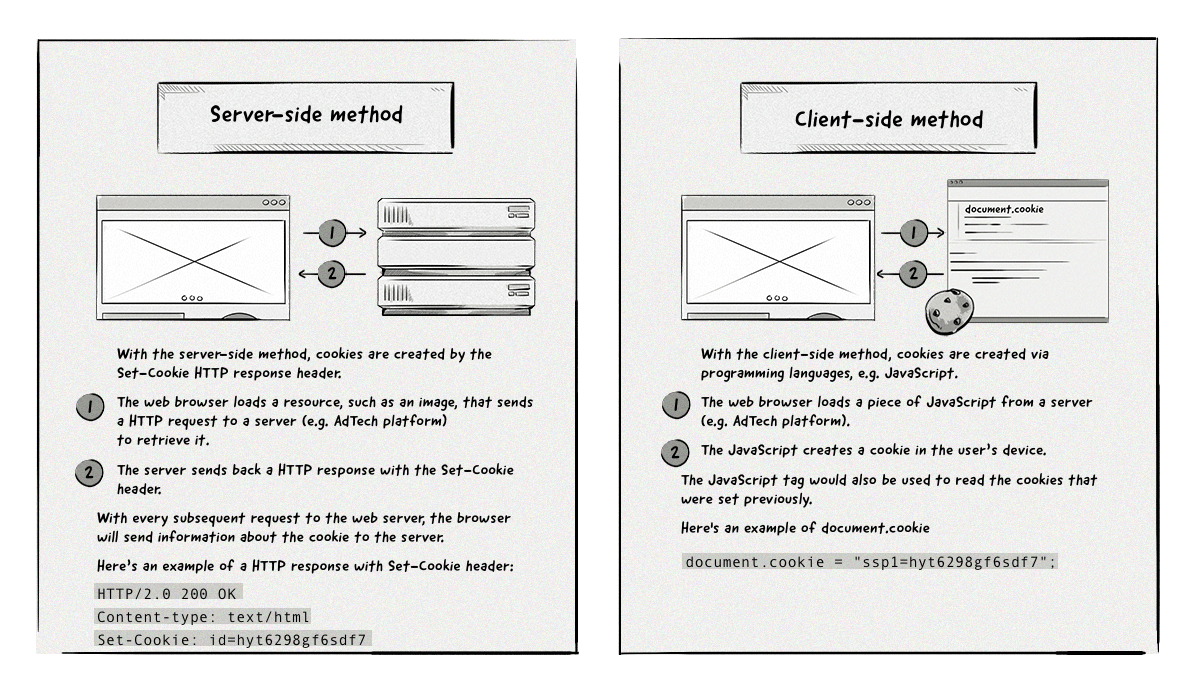

How First-Party and Third-Party Cookies Are Created

The image below illustrates how first-party and third-party cookies are created by web browsers.

With the first method, AdTech platforms can either create cookies via the ad creative when it’s retrieved from their server or via a 1×1 transparent image. The goal of the 1×1 transparent image is simply to get the browser to send a request to the AdTech platform’s browser so it can create a cookie when it returns the image.

Comparison of First-Party and Third-Party Cookies

Remember flash cookies?

Flash cookies act similarly to HTTP cookies but are created via the Adobe Flash plugin, which is used to power things like videos and mobile apps.

About a decade ago, the use of Flash cookies raised a number of privacy concerns due to the lack of control users had with deletion. Flash cookies were stored in a separate folder on devices and could only be managed via the Adobe Flash settings, meaning that when a user deleted their HTTP cookies, their Flash cookies remained intact.

This led to Adobe and popular web browsers making changes to how Flash cookies were handled. Since then, Flash cookies are treated the same as HTTP cookies, so if a user deletes their HTTP cookies, Flash cookies would also be deleted.

For this reason, and because many videos and games are played via HTML5 nowadays, the use and availability is much lower than in the past, therefore they aren’t used for online advertising anymore.

Cookie Syncing

Because cookies created by one domain can’t be read by another, this makes it hard for AdTech platforms to identify the same user on a given web page.

For instance, if a user visits example.com, the cookie that the SSP creates will be different than the one a DSP creates.

To help AdTech platforms identify the same user on different websites, a process known as cookie syncing was developed.

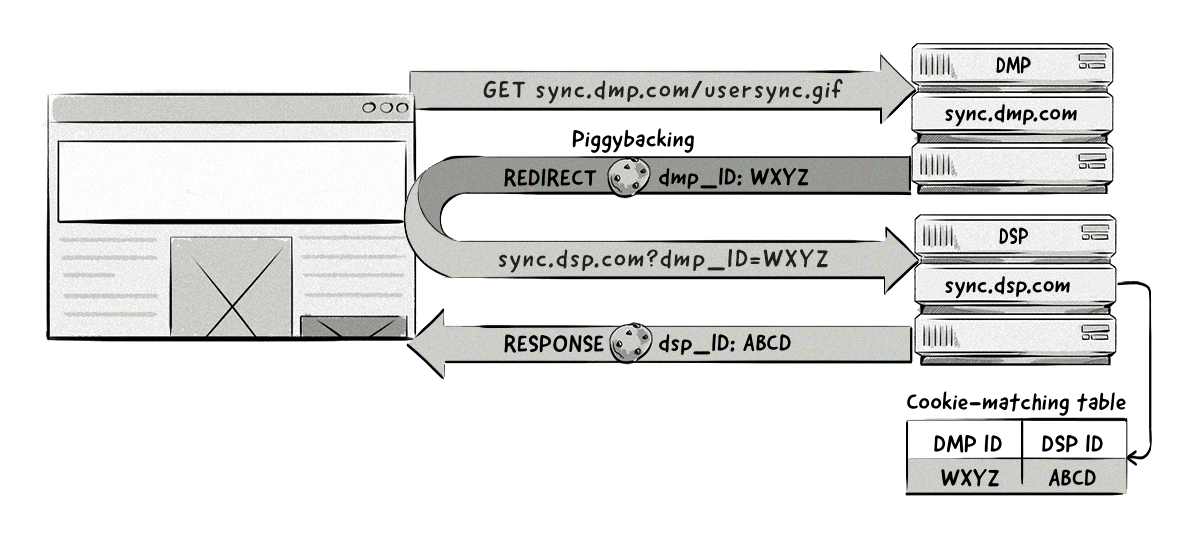

Cookie syncing is the process of mapping one user ID (stored in a cookie) from one technology platform to another (e.g. from a DMP to a DSP). The eventual goal of syncing cookie IDs is to share data about the user between different platforms, which allows them to better target audiences with online advertisements. The two platforms would have a formal agreement between one another and would need to set up partner IDs on their platforms and add cookie-syncing pixels in their codes.

The cookie-syncing process is carried out by a number of different platforms in the ecosystem, including data-management platforms (DMPs), demand-side platforms (DSPs), ad networks, ad exchanges, supply-side platforms (SSPs) and many more.

How Does Cookie Syncing Work?

There are two main parts to the cookie-syncing process:

- Mapping of cookie IDs

- Sharing of user data contained in the cookies

Mapping Cookie IDs

Each time a user visits a website that contains a cookie-syncing pixel or other advertising-platform tag, the browser sends a request to a technology platform – for example, a DSP.

The DSP creates a unique ID for that user, if one doesn’t exist already, and stores that ID in a cookie. The DSP then redirects (http redirect) the request to the cookie-syncing endpoint URL that has been supplied by a different advertising platform – for example, a DMP – and passes the user ID as a URL parameter.

The DMP’s server reads the user ID created by the DSP from the parameter in the URL and reads the cookie in its own domain to see if it already has an ID for this particular user. If it doesn’t, the server creates a user ID of its own, then stores the information about its own ID and the DSP’s ID in a cookie-matching table.

The DMP can pass its own identifier back to the DSP so that the sync is bidirectional. It does this by doing a pixel redirect back to the DSP and passes its own ID as a parameter.

Now, both the DSP and DMP have each other’s user IDs in each other’s databases.

The image below illustrates how the cookie-syncing process looks.

Sharing Data Between Two Platforms

Once the cookie IDs have been synced between two AdTech platforms, they can share or request data contained in the cookies by referencing each other’s user IDs.

Typically, this process is done via a server-to-server integration with the data being transferred in large batch files. Unlike the cookie-matching part that happens in real-time, sharing the data between platforms happens at a specified time – for example, once a day.

It’s important to note that cookie syncing is only performed in web browsers (desktop or mobile) across all types of online advertising, including display, native and video ads.

The reason for this is because unlike native mobile apps that use the device’s advertising ID (e.g. IDFA and AID) as a way to identify users, web browsers don’t emit a consistent user identifier. Cookies from one domain can’t be accessed by a platform operating under a different domain, so the only way to identify a user across different websites is by using their cookie ID.

Problems With Cookie Syncing

Although cookie syncing allows AdTech companies to identify users across the web, it has a couple of inherent problems:

- The more cookie syncs a web page needs to perform, the longer it takes the page to load, which can result in a bad user experience.

- Cookie-match rates vary among platforms, with the average rate sitting between 40-60%.

- Cookie churn, caused by third-party cookies being blocked by default or regularly deleted by users, means the effectiveness and accuracy of cookie syncing decreases.

Cookie Respawning

Cookie respawning is a process whereby a cookie reappears, or respawns, after it has been deleted.

It does this by using backed-up data stored in additional files on a user’s device and then respawning the cookie later when a user accesses the same website again.

The process looks like this:

- A user accesses a website.

- The website creates a cookie.

- The cookie tags the user’s browser with a unique identifier that is not easy to delete.

- The user leaves the website and deletes their cookies.

- The user accesses the website again and the new cookie recognizes the identifier in the browser and respawns the original cookie.

There are two main ways a cookie can be respawned:

Flash cookies: Companies use the Adobe Flash Player browser plugin to store information about the user on their computer and to respawn cookies. As mentioned above, flash cookies are rarely used these days.

HTML5: HTML5 local storage and cache cookies use entity tags (ETags) to respawn HTML cookies by recognizing the persistent identification element (PIE) created by JavaScript and Flash.

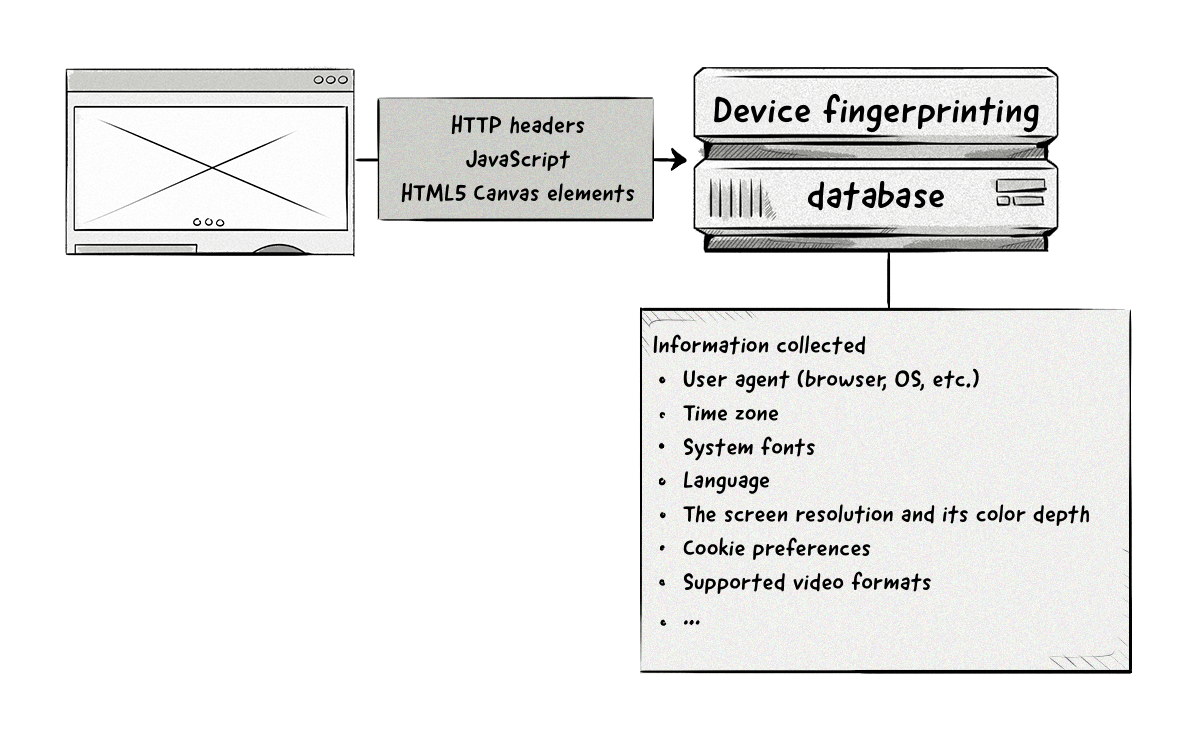

Device Fingerprinting

Device fingerprinting is a technical process that aims to identify and track online users based on the characteristics of their devices. It works by gathering bits of information to create an identifier, which is then used to identify individuals across different websites.

While many different users may own the same device, each one will be configured slightly differently according to the user’s individual preferences and requirements. Data about these configuration changes can be aggregated to create a recognizable “device fingerprint.”

Information used to create a device fingerprint can include:

- Browser version

- Operating system

- Language

- Items installed (plugins, fonts, etc.)

- Location and time-zone settings

- Browser settings

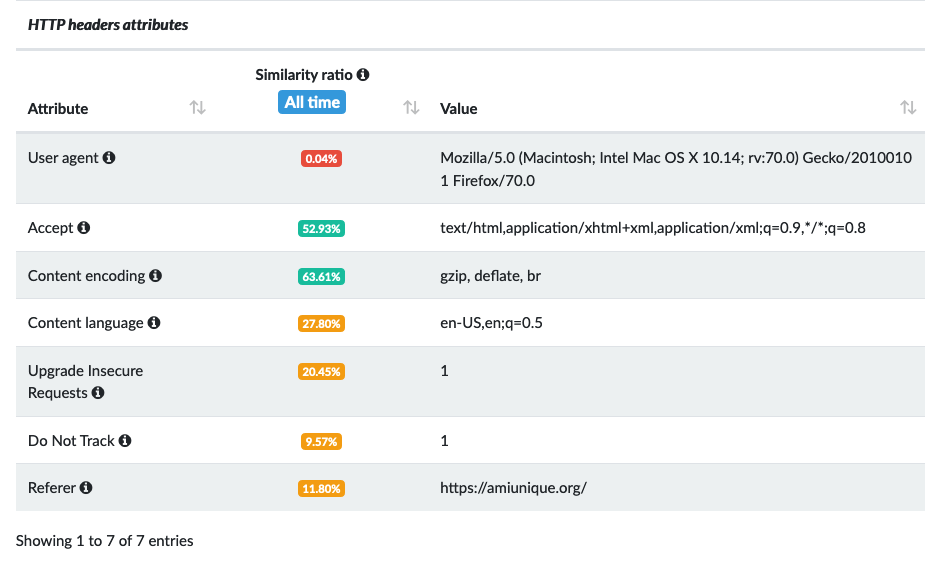

Here’s an example of the HTTP header attributes that are used to create a device fingerprint:

The image above illustrates how unique certain attributes are to the user’s device, as represented by the similarity ratio.

For example, the user agent has a similarity ratio of 0.04%, meaning it is very unique to this user.

The more unique the attribute is, the more easily it can be used to identify a user.

Why Do Companies Use Device Fingerprinting?

Device fingerprinting emerged to address a number of challenges that AdTech and analytics companies faced around the availability and reliability of cookies.

Over the past decade, online users have regularly deleted and blocked cookies via ad-blocking plugins and browser settings to protect their online privacy.

This has made it harder for AdTech and analytics companies to identify and track users across the web.

Although device fingerprinting isn’t as accurate as cookies, it can be used as a backup when cookies are blocked or deleted, as well as in combination with cookies to help increase the chances of identifying a particular user.

How Does Device Fingerprinting Work?

Creating a device fingerprint requires collecting data and information about a user’s device, which is typically collected via:

- The user agent and accept headers

- JavaScript

- Flash plugin (if installed)

- HTML5 canvas elements

What Is canvas fingerprinting?

Canvas fingerprinting is similar to device fingerprinting, but only uses the HTML5 canvas element to identify a browser.

Companies use a piece of JavaScript to instruct the user’s web browser to draw a picture via the canvas. Each browser will draw a slightly different image, meaning the image is unique (or highly unique) to the device. This allows companies to identify and track users across the web.

This information is then combined and a unique hash is created and assigned to that device.

Unlike cookies that are stored on a user’s device (client-side), device fingerprints are stored in a database (server-side) due to the amount of information they collect.

HTML5 Local Storage

HTML5 local storage is a newer method for collecting and storing data about users.

There are two variants of local storage:

localStorage: Stores data with no expiration date.

sessionStorage: Only stores data for the session – i.e. data is deleted when the user closes the browser tab.

Compared to cookies, HTML5 local storage provides the following benefits:

- More storage: HTML5 local storage can store up to 5MB of data, compared to 4KB (4096 bytes) for cookies.

- More availability: Most browsers don’t delete HTML5 local-storage data and it isn’t typically blocked by ad-blocking plugins or browser settings.

- No web-server calls: To create cookies, a request needs to be sent from a web page to a web server and then back again. HTML5 local storage is created via JavaScript and doesn’t require any calls to servers.

The main downside from an AdTech perspective is that it is domain- and protocol-specific, meaning users can’t be identified across different domains.

ETags

An entity tag (ETag) is an HTTP response header used to improve the efficiency of cache and save bandwidth.

It does this by assigning an identifier to content (e.g. images) on a web page.

When a web page loads, the browser sends off a request to various web servers to retrieve the contents.

If a URL has an ETag set for a given resource (e.g. an image), the web server will compare the incoming ETag with its own ETag. If the two match, it means the image hasn’t changed. The web server will then tell the browser that the image in the cache is still up to date and can be displayed on the web page.

AdTech companies can identify users by comparing the ETags sent from a user’s browser with their records.

To achieve this, a publisher would need to install an AdTech’s HTML code on their website, typically a 1×1 transparent image (aka pixel).

When the page loads, the code will load and send a request containing an ETag to the AdTech vendor’s server.

If the ETag coming from the publisher matches the ETag in the AdTech vendor’s server, they would be able to identify the browser.

Because it’s a standard HTTP request, the AdTech vendor could also collect information about the user, such as their operating system, browser type, language, location and the URL they are visiting. This information can be used to create audiences and later for ad targeting.

Information created via ETags will be deleted if a user clears or deletes their browser’s cache.

Evercookies

An evercookie is a cookie that is saved to various storage locations in a user’s browser and device. It was created by the privacy and security researcher, Sammy Kamkar.

Companies can create evercookies via a JavaScript API, which saves data in various locations. If the user deletes data from one location, such as HTTP cookies, the JavaScript API will recognize that this data has been removed and simply respawn the cookie from one of the other storage locations.

The current list of storage locations includes:

- Standard HTTP cookies

- Local shared objects (Flash cookies)

- Silverlight Isolated Storage

- Storing cookies in RGB values of auto-generated, force-cached PNGs using HTML5 canvas tag to read pixels (cookies) back out

- Storing cookies in web history

- Storing cookies in HTTP ETags

- Storing cookies in web cache

- Window.name caching

- Internet Explorer userData storage

- HTML5 session web storage

- HTML5 local web storage

- HTML5 global storage

- HTML5 web SQL database via SQLite

- HTML5 IndexedDB

- Java JNLP PersistenceService

- Java CVE-2013-0422 exploit (applet sandbox escaping)

Because evercookies are much harder to delete than regular HTTP cookies, they raise a number of privacy concerns.

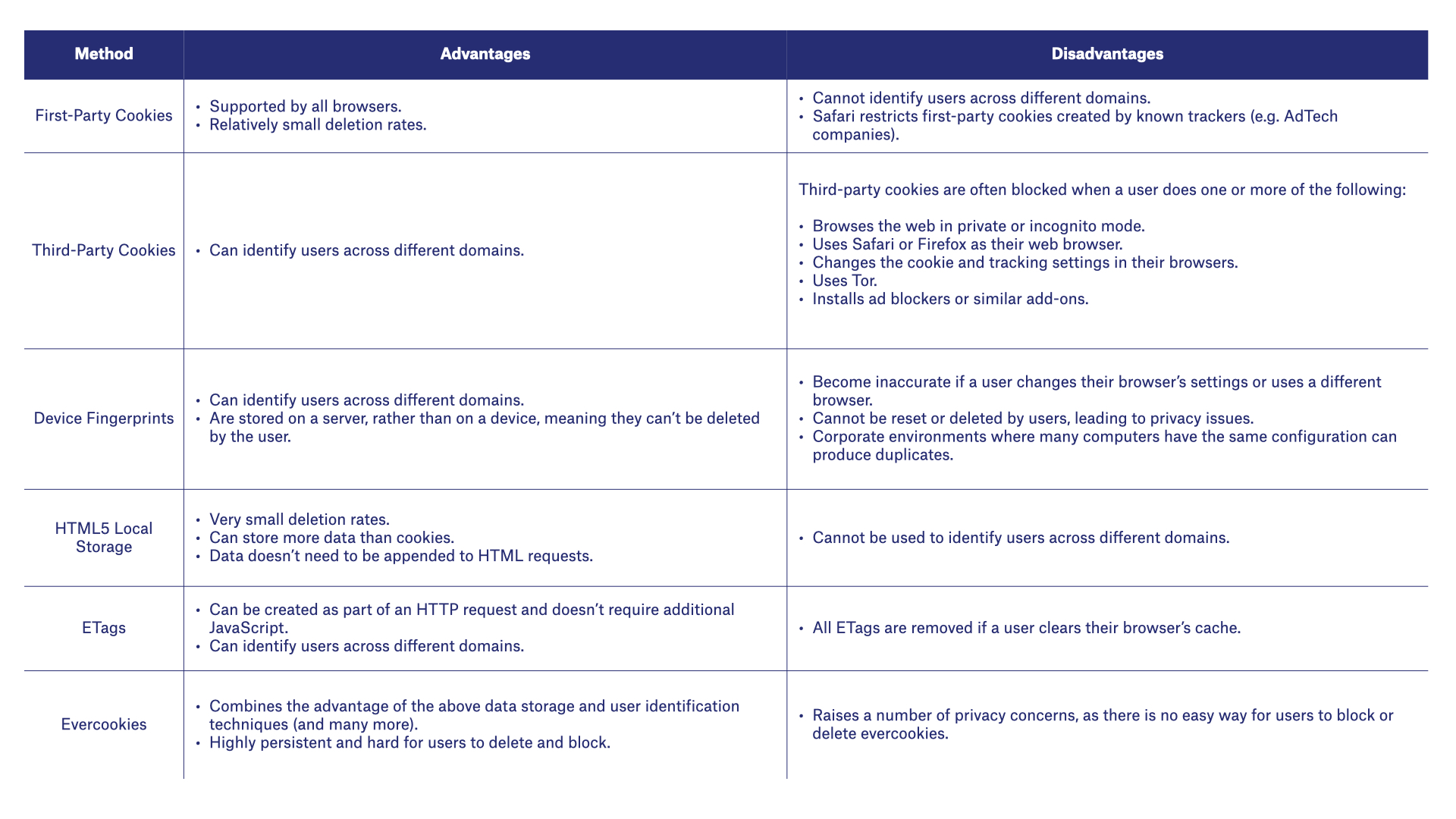

The table below outlines the advantages and disadvantages of the various methods used to identify users via web browsers.

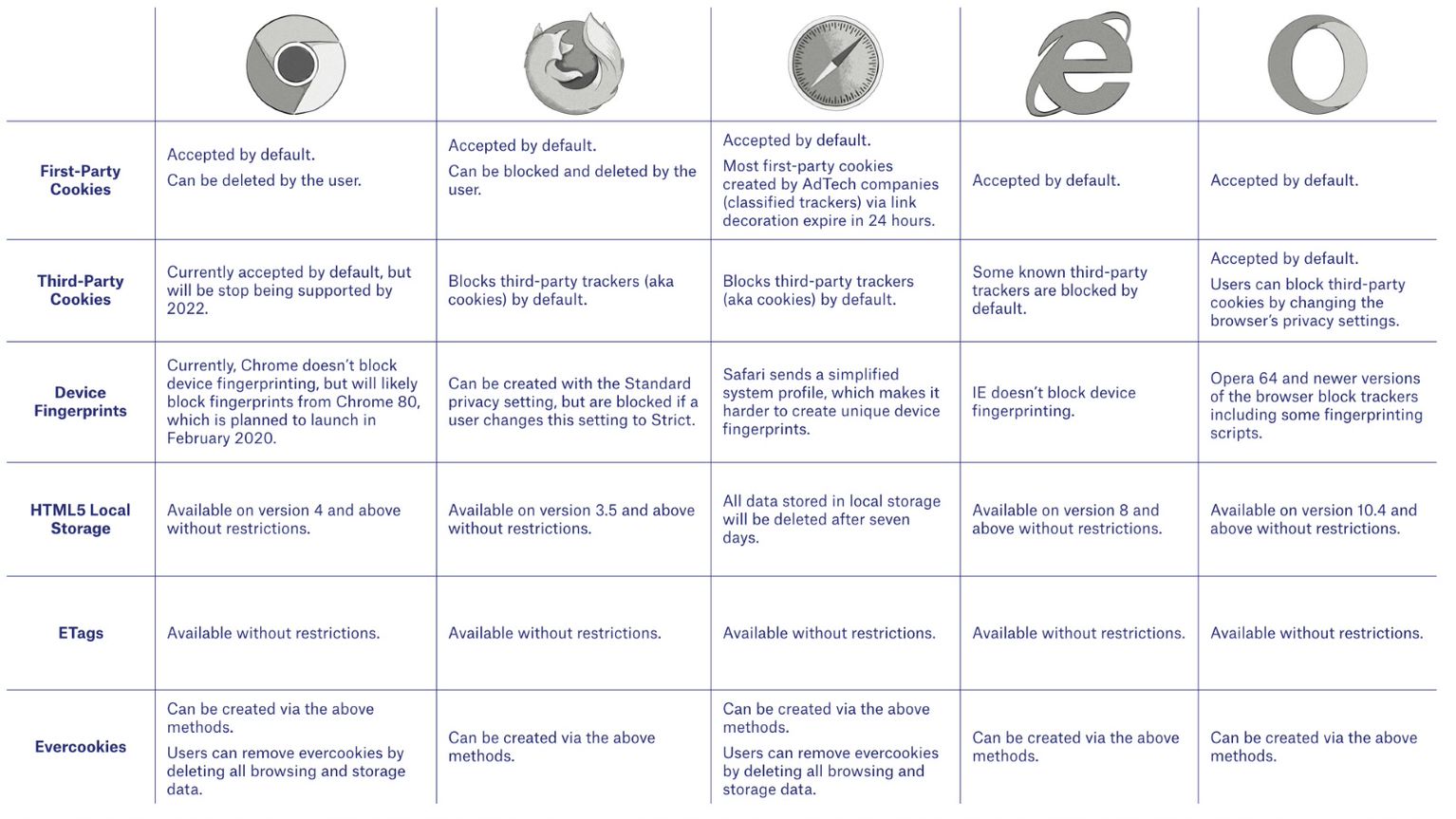

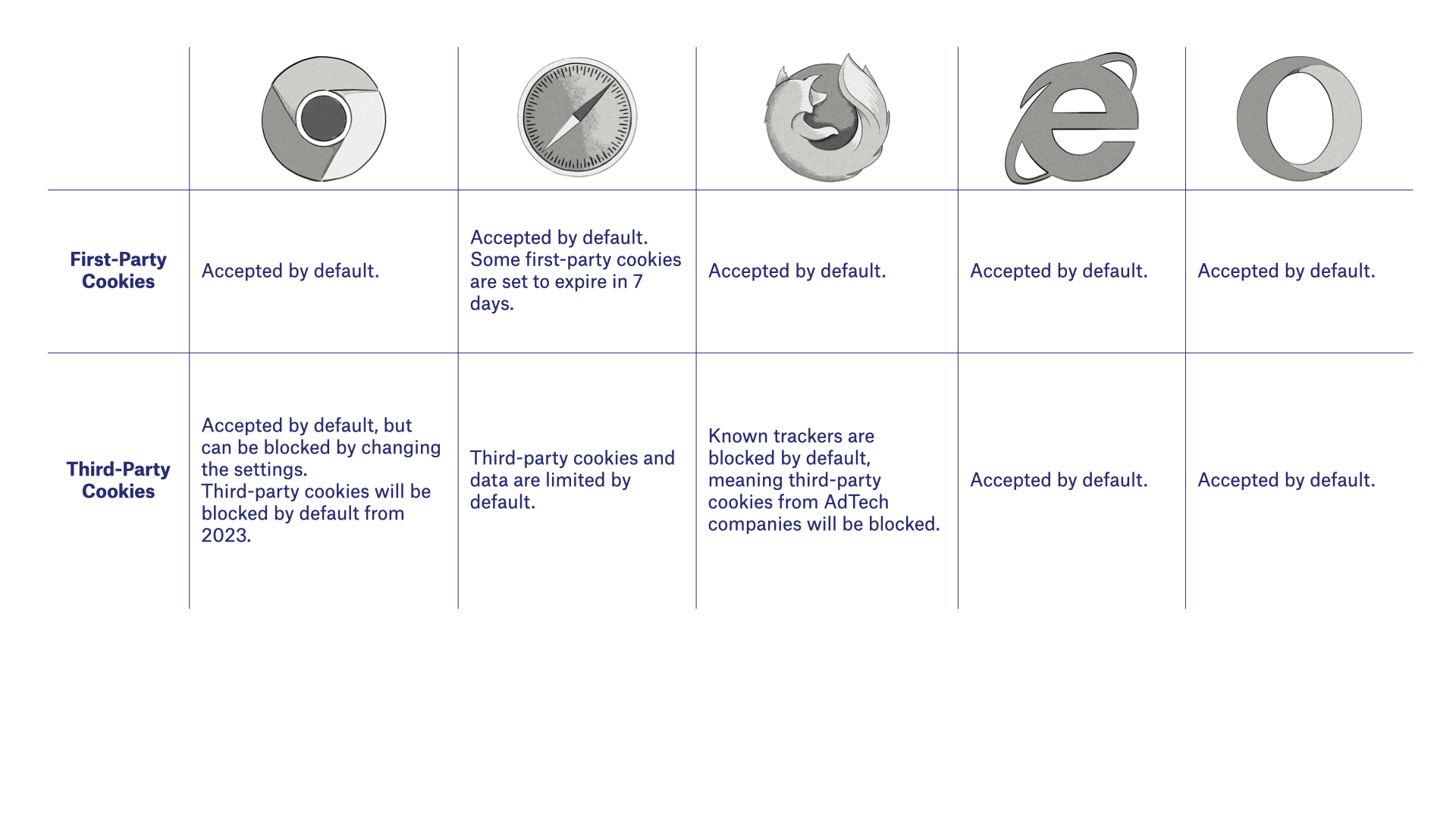

How Different Web Browsers Handle Cookies, Device Fingerprints and Local Storage

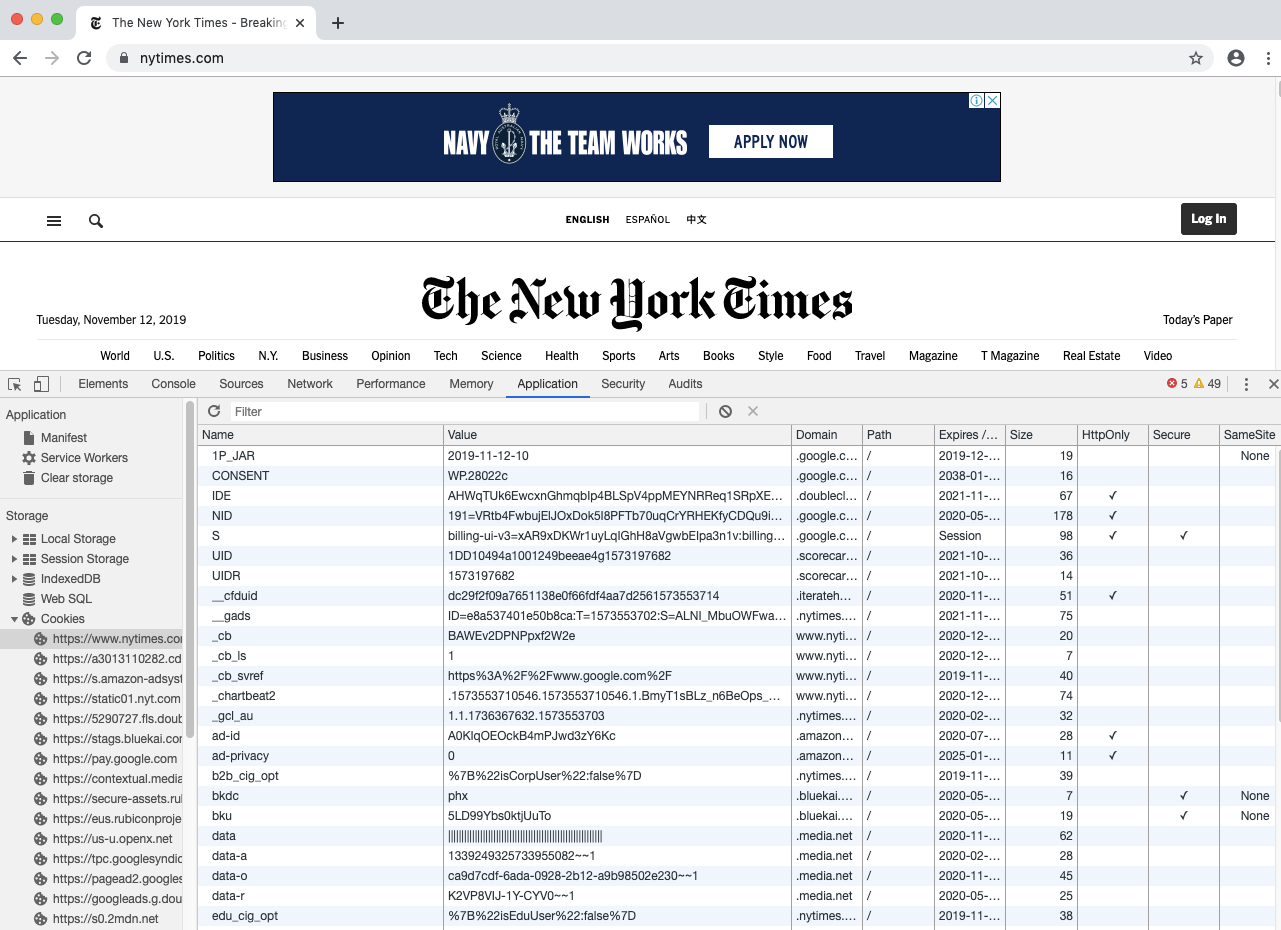

How to See Which Cookies Are Saved During a Web Session

You can see which first-party and third-party cookies, as well as data in other storage locations, are created during a session in your web browser by doing the following:

Chrome: Right-click on the page ⇨ Inspect ⇨ Application

Firefox: Right-click on the page ⇨ Inspect Element ⇨ Memory

Safari: Right-click on the page ⇨ Inspect Element ⇨ Storage

Internet Explorer: Press F12 ⇨ Console tab ⇨ Type “sessionStorage” or “localStorage” in the console

Edge: Follow the above instructions for Chrome (it looks the same because both browsers are based on Chromium)

Opera: Follow the above instructions for Chrome (it looks the same because both browsers are based on Chromium)

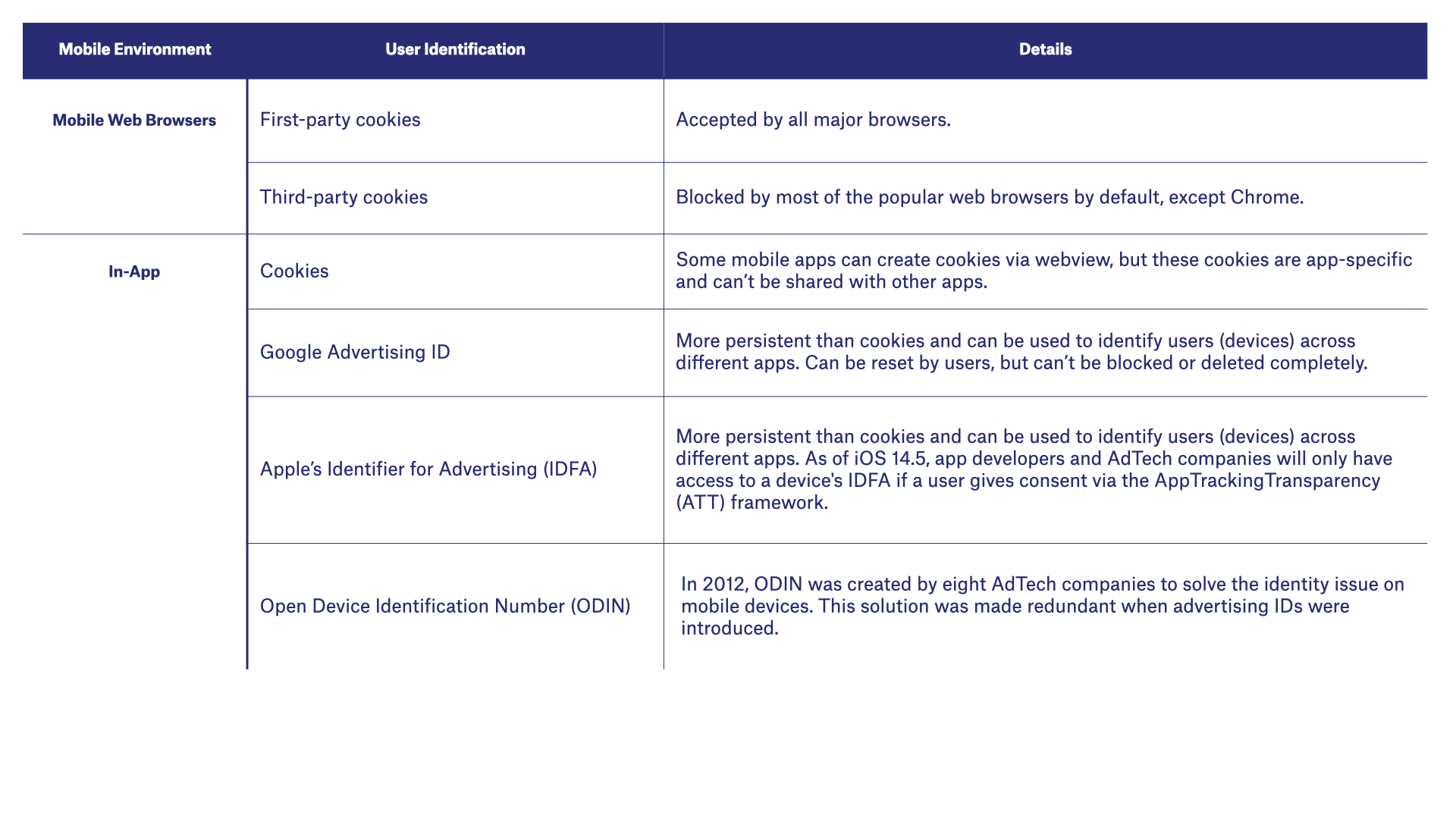

Mobile Devices

In the section above, we explained how users can be identified when browsing the Internet via a web browser on a desktop or laptop.

Now we will look at the ways in which advertisers can identify and track users when using a web browser and apps on mobile devices, such as smartphones and tablets.

Here’s an overview of the user-identification methods on mobile devices:

Mobile Web Browsers

Web browsers on mobile devices typically handle cookies in the same way as on desktop or laptops.

Here’s an overview of how web browsers handle cookies on mobile devices.

Mobile Apps (In-App)

Identifying users in mobile apps (aka in-app) can consist of the following methods:

Cookies

To display online content inside web apps, some app developers use a piece of technology called webview.

Webview can create cookies and store them inside a secure location on the device, which is known as a sandbox or sandboxed environment.

The main issue for AdTech is that these cookies are app-specific, meaning they can’t be shared across different apps, therefore AdTech companies can’t identify the same user across different apps even though they are using the same device.

Mobile devices include an advertising ID:

Advertising IDs

Mobile devices include an advertising ID:

- Google’s Android ID (AID)

- Apple’s ID for Advertising (IDFA)

- Microsoft’s Advertising ID (aka Advertising Identifier)

These IDs are more persistent than web cookies, and even though users can’t disable or remove these IDs like they can with cookies, they can easily reset them.

The exception to this is Apple’s IDFA, which is only available to app developers and AdTech companies if users opt in via the AppTrackingTransparency (ATT) framework. This framework applies to apps running on iOS 14.5 iPadOS 14.5, and tvOS 14.5 and above.

Read more about Apple’s ATT framework in chapter 14. User Privacy in Digital Advertising.

How Are Advertising IDs Used for Identification in Mobile Apps?

Advertising IDs are passed from mobile apps to AdTech platforms. Below is an example of a real-time bidding (RTB) bid response showing a mobile ID in the ifa field.

"device": {

"dnt": 0,

"ua": "Mozilla/5.0 (iPhone; CPU iPhone OS 6_1 like Mac OS X)

AppleWebKit/534.46 (KHTML, like Gecko) Version/5.1 Mobile/9A334 Safari/7534.48.3",

"ip": "123.145.167.189",

"ifa": "AA000DFE74168477C70D291f574D344790E0BB11",

"carrier": "VERIZON",

"language": "en",

"make": "Apple", "model": "iPhone",

"os": "iOS", "osv": "6.1",

"js": 1,

"connectiontype": 3,

"devicetype": 1,

"geo": {

"lat": 35.012345, "lon": -115.12345,

"country": "USA",

"metro": "803",

"region": "CA", "city": "Los Angeles", "zip": "90049"

} Did you know?

Apart from advertising IDs, there are even more persistent IDs in mobile devices – Universal Device Identifier (UDID) and Media Access Control (MAC) Address.

These IDs are associated with the hardware of mobile devices and can’t be disabled or reset by users. There was a time when Apple and Google allowed access to these IDs, but due to privacy reasons (i.e. they can’t be disabled or reset), they stopped providing access to them in 2012 and 2013 respectively.

Open Device Identification Number (ODIN)

Back in 2012, eight mobile-advertising companies came together to develop an alternative to the Universal Device Identifier (UDID) and Media Access Control (MAC) Address.

The solution was called the Open Device Identification Number (ODIN).

However, this solution has sinced been replaced by advertising IDs provided by Google and Apple.

User Profile Matching

As we’ve just covered, identifying users via one method can be incredibly difficult and inaccurate.

The problem is exacerbated when users use more than one device, which is often the case nowadays.

Currently, there is no method that allows AdTech vendors to identify users as they move from one device to another.

The reason for this is because the traditional ways of identifying and tracking users with cookies in web browsers wasn’t designed for the multi-device world.

There are, however, two ways you can identify and track the same user as they move across different devices with reasonable accuracy: deterministic matching and probabilistic matching.

Deterministic and Probabilistic Matching

Deterministic and probabilistic matching are processes used to identify users across different devices.

Companies will often use both deterministic and probabilistic matching together to increase match rates.

What Is Deterministic Matching?

Deterministic matching involves creating a profile of users consisting of different pieces of data about them.

These profiles are then used to identify users on different devices by looking for a common identifier.

Common identifiers can include:

- Email address

- First and last name (if uncommon)

- Address

- Date of birth

- Phone numbers

It’s important to note that this information would be hashed when it’s collected to remove personally identifiable information.

How Does Deterministic Matching Work?

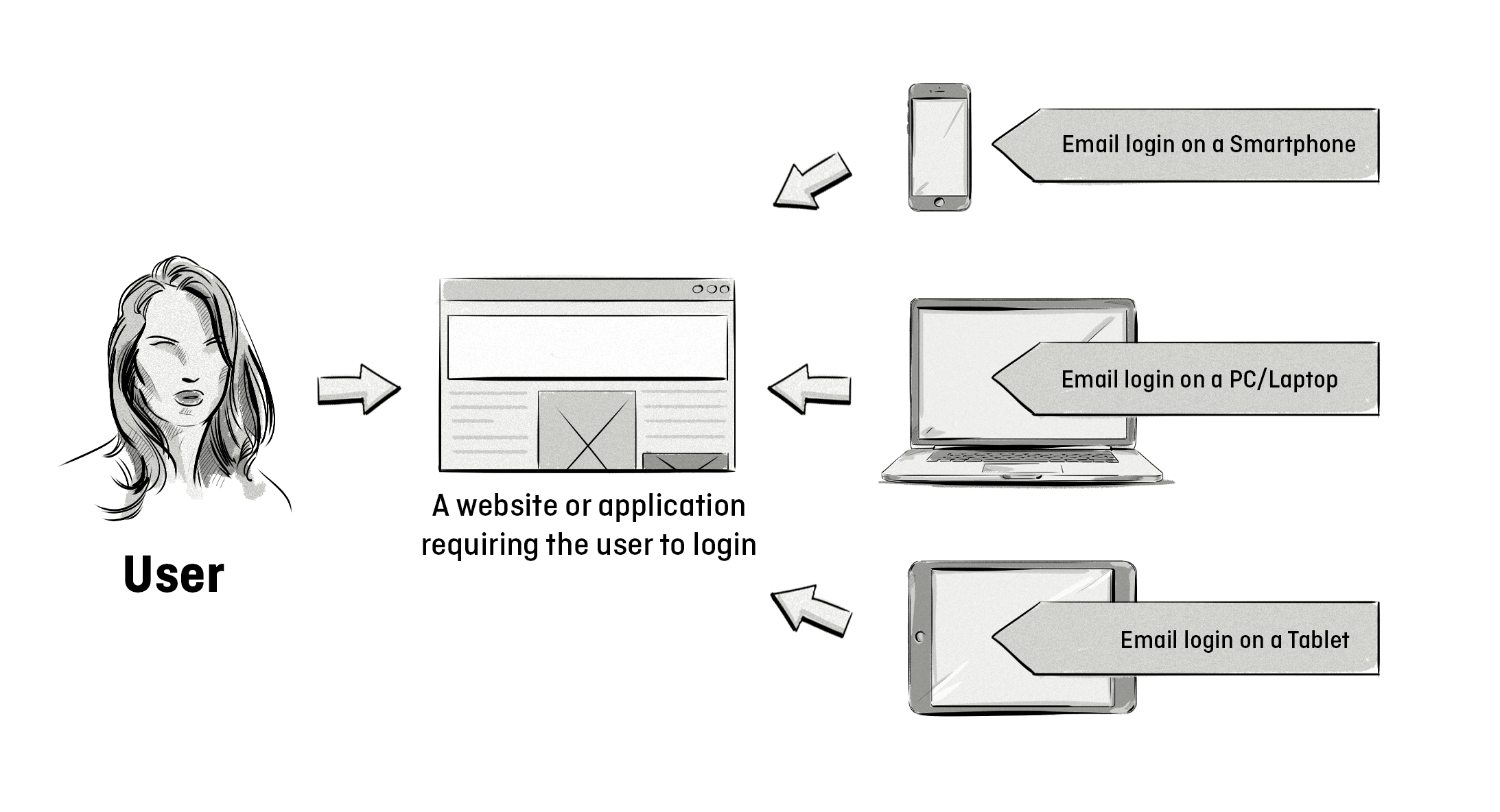

The most common way to deterministically match users in online advertising and marketing is by using an email address as the common identifier, as this is unique to the user and is often available in different data sets.

Companies like Facebook, Google, Twitter and LinkedIn are able to deterministically match users with ease and accuracy because they require users to create accounts and sign in using an email address to access their applications and sites on different devices.

The main advantage of deterministic matching is accuracy. It’s much more accurate than probabilistic matching; most deterministic matching rates are around 80-90%.

The main drawback, however, is that it lacks scale, as most companies don’t collect this type of data and email addresses aren’t typically used for buying and selling online advertising.

To address the issue of scale, publishers are requiring users to create an account or subscribe using their email address to access certain content.

The two main ways they can do this are:

By way of encouragement: Publishers can encourage visitors to provide an email address in exchange for more access and content.

By way of force: Publishers can gate their content and restrict access to it unless users subscribe or create an account.

These tactics would work well with large publishers like news sites, as they typically have an engaged audience that regularly visits their sites compared to small- and medium-sized publishers, as not everyone will want to create an account just to read a few blog posts.

What Is Probabilistic Matching?

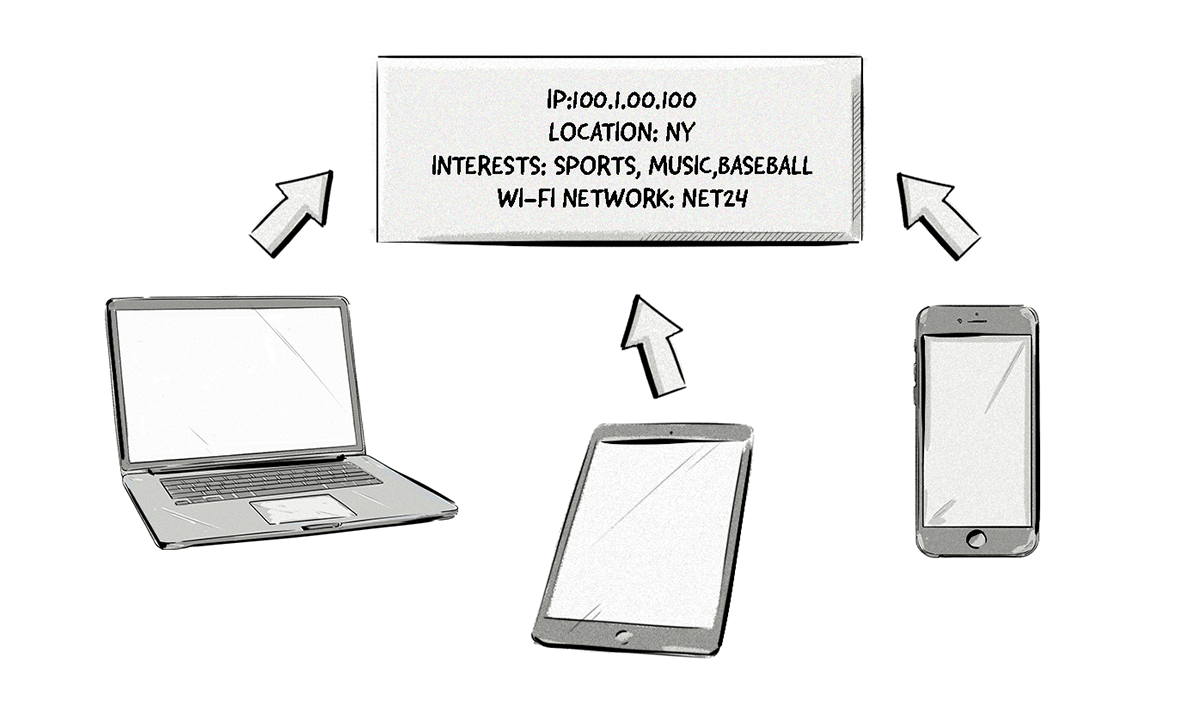

Unlike deterministic matching that uses a common identifier, such as an email, to match users to devices and applications, probabilistic matching uses various pieces of data, algorithms, and statistical modeling to make a match.

The type of data used for probabilistic matching includes:

- IP address

- Location

- Interests, behavior, and browsing history

- Wi-fi networks

The image below illustrates how one user operating all three devices can be probabilistically matched to all of them based on their IP address, location, interests and Wi-fi network.

Although probabilistic matching isn’t as accurate as deterministic matching, it often uses deterministic data sets to train the algorithms and increase accuracy.

This process involves exposing the algorithms to a small group of deterministic and probabilistic data sets (a couple hundred thousand) and training them to make connections (identify the same user).

Then, the algorithms are applied to hundreds of thousands or even millions of data sets that don’t contain deterministic matching.

Even though probabilistic matching lacks the accuracy of deterministic matching, the main benefit is that it offers better scale and reach.

However, there are a few downsides to probabilistic matching, including:

- Lack of transparency of the matching methods and accuracy.

- Redundant and outdated data.

- Decline in the availability of the data due to data-protection and privacy laws, such as the GDPR, requiring consent to collect IP addresses, location and other data (more on this below).

What Are Deterministic and Probabilistic Matching Used For?

Because deterministic and probabilistic matching aim to identify users across different devices and apps, their main use cases are cross-device targeting and cross-device attribution.

Cross-device targeting: Identifying users across different devices and showing ads based on their behavior on different devices – e.g. which websites they visit and what products they purchase.

For example, a user might view a jacket on a laptop and then see the same jacket or similar product in an ad on their smartphone.

Cross-device attribution: Similar to cross-device targeting, this focuses on attributing impressions and clicks to conversions and purchases made on different devices.

For example, if a user clicked on an ad for running shoes on their smartphone, but purchased them on their laptop, cross-device attribution would be able to attribute the ad click on the smartphone with the purchase on the laptop.

The Main Challenges With Identifying Users on Web Browser and Mobile Apps

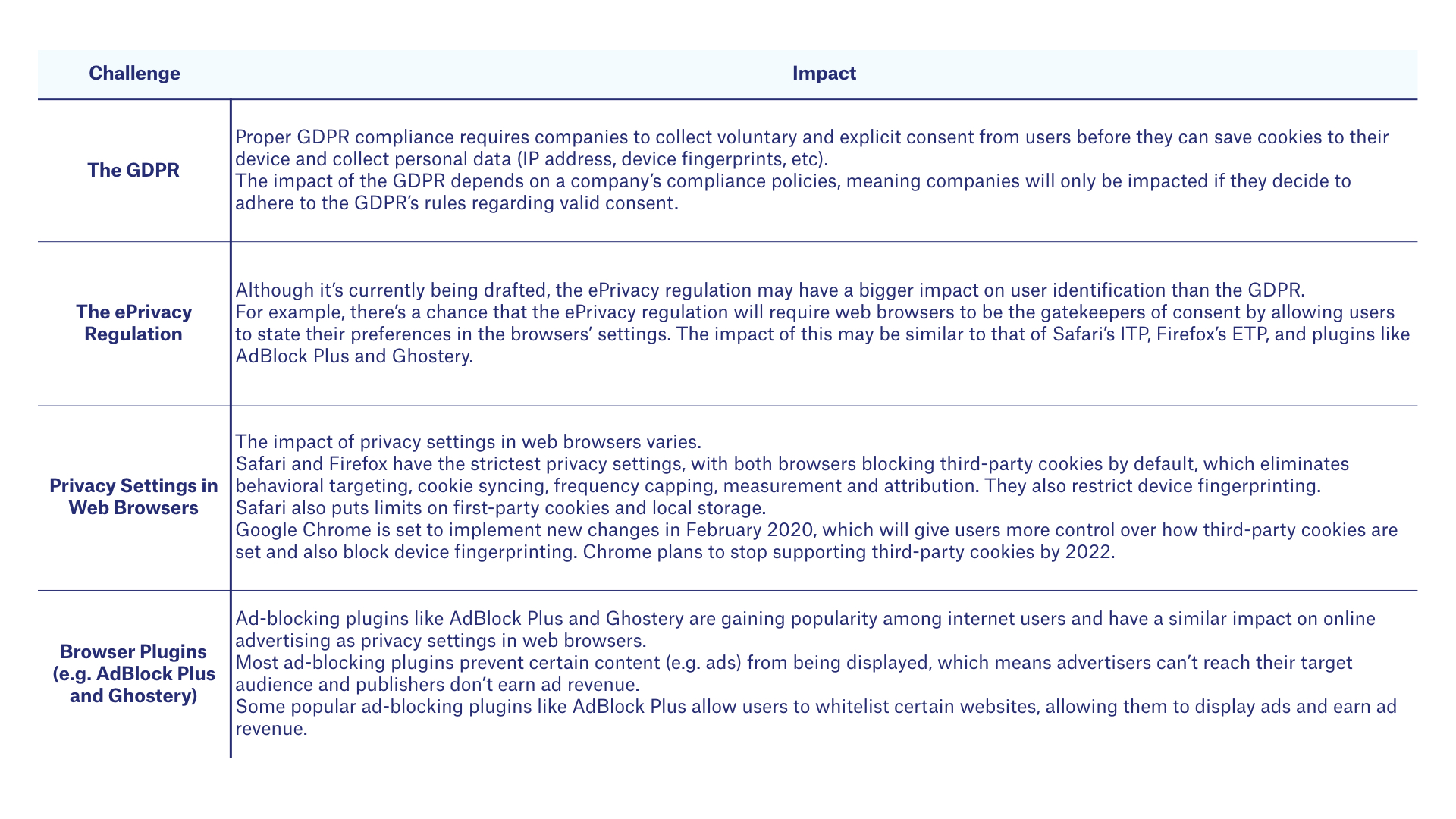

As we’ve mentioned throughout this chapter, AdTech companies face a number of challenges with identifying users across web browsers and mobile apps.

The table below highlights the main challenges.

Solutions to the Identity Problem

Due to the direct and severe impact privacy laws and privacy settings are having on identity in online advertising, and the inefficiencies of cookie syncing, various companies and groups have proposed numerous ID solutions.

The main goals of these ID solutions are to:

- Identify users on web browsers as they move from website to website.

- Reduce page-load latency caused by cookie syncing.

- Compete with the walled gardens of Google and Facebook that have access to deterministic data and can offer advertisers better targeting, measurement and attribution.

There are many companies that are providing solutions to the ID problem, but here are the main ones:

The Trade Desk offers AdTech and data companies free access to its Unified ID solution (TTID), which is hosted under the adsrvr.org domain. In July 2020, The Trade Desk revealed that it would be releasing a new version of its Unified ID solution. This newer version of Unified ID, often referred to as UID2, is open source and can be used by all companies, not just those working with The Trade Desk, and will be underpinned by hashed and encrypted email addresses.

The Advertising ID Consortium is powered by the LiveRamp ID and hosted under the AppNexus domain, even though AppNexus withdrew from the consortium when it was acquired by AT&T in August 2018.

ID5 is a company that allows publishers, data companies and AdTech vendors to outsource their cookie syncing processes with their partners and use ID5’s cookie-matching table.

The Secure Web Addressability Network (SWAN), aka SWAN.community, is another ID solution that is very similar to UID2, but with a few differences. The main companies behind SWAN.community are Zeta Global, 51Degrees, Open X, ENGINE Media Exchange (EMX), PubMatic, Rich Audience and Sirdata.

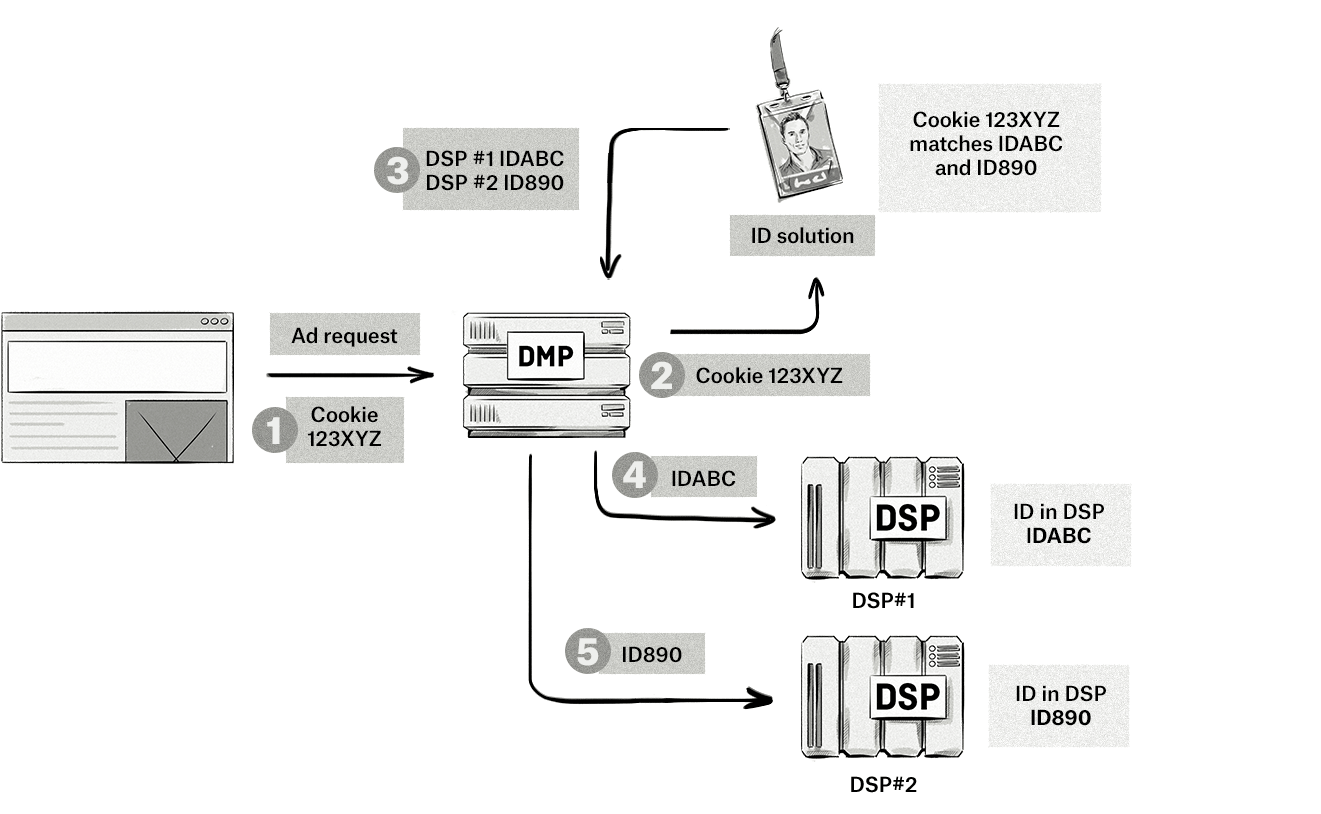

How Do These ID Solutions Work?

Most of the ID solutions work similarly to each other and act as an ID distribution and retrieval service. They manage the cookie-syncing and ID-matching processes on behalf of different AdTech platforms, so instead of DSPs and SSPs having to sync cookies between themselves, they could centralize the process via an ID solution.

Step-by-step explanation:

- The browser sends an ad request to a DMP with the cookie ID of the user.

- The DMP sends the cookie ID to the ID solution and aims to match it with existing IDs.

- In this case, the cookie ID matches two IDs belonging to DSPs that the DMP has a partnership with.

- The DMP sends the IDs from the ID solution to its DSP partners. The DSPs use the IDs from the DMP to identify which audience the user belongs to and then bid accordingly.

Although these ID solutions solve some of the challenges related to identity in AdTech, they don’t provide a complete solution and are still impacted by privacy laws and privacy settings.

ID and Device Graphs

Apart from the ID solutions mentioned above, there are many companies that offer ID resolutions services like ID and device graphs.

The main goal of these solutions is to piece together IDs from online and offline channels to create a centralized view of consumers, rather than to use these IDs for online media buying.

Below are just some of the companies that provide ID and device graphs:

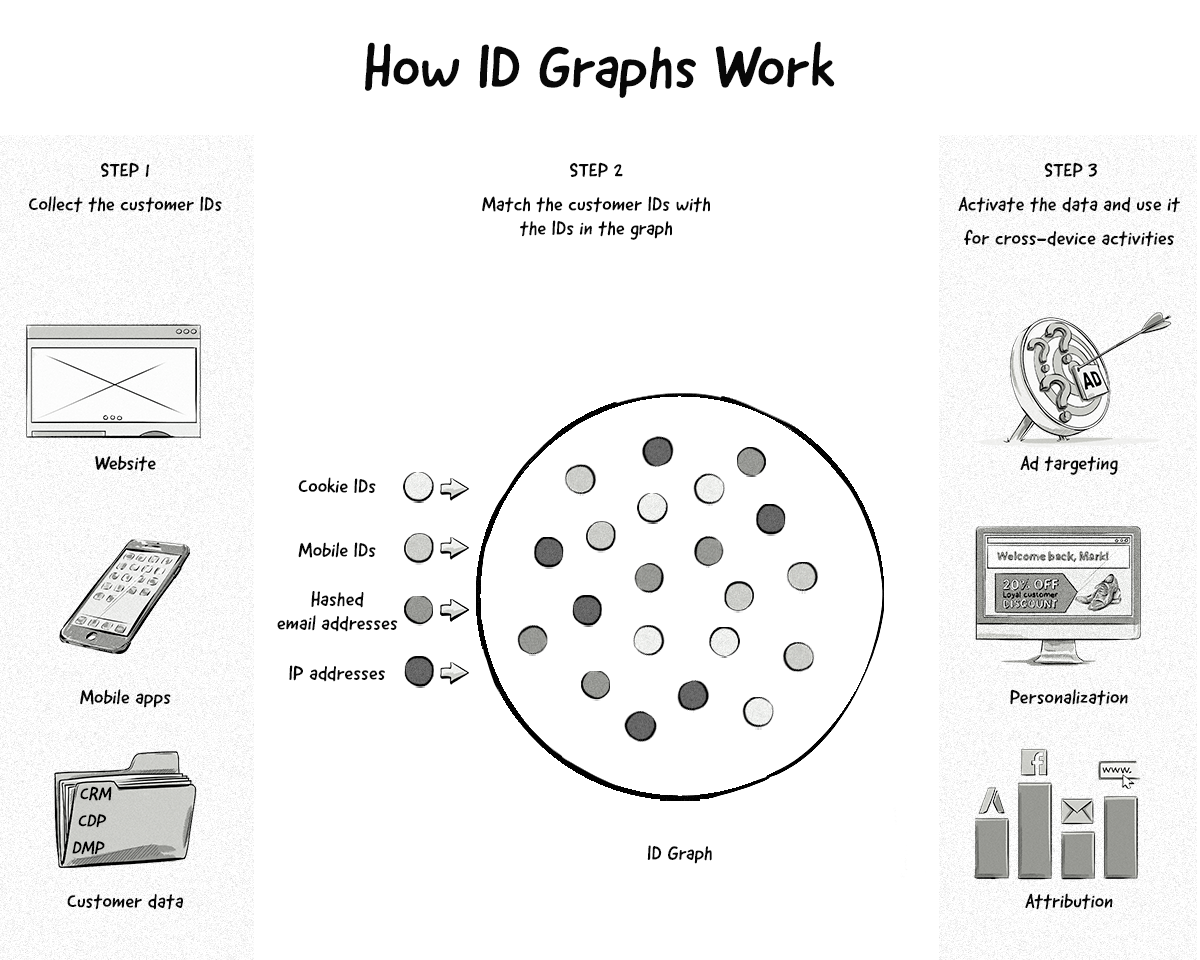

How Do ID Graphs Work?

Here’s an explanation of how ID graphs work:

Step 1. Data collection: A company would send its customer IDs (i.e. first-party IDs) to the ID graph. These first-party IDs could be taken from websites, mobile apps, and customer and data platforms (e.g. CRMs, CDPs, and DMPs).

Step 2. Match the customer IDs with the IDs in the graph: The company’s first-party IDs would then be matched with all the other IDs in the graph, which would be done using a combination of deterministic and probabilistic matching.

Step 3. Activate the data for cross-device activities: The company can now identify their customers across different devices and channels and run various cross-device activities, like ad targeting, personalization, and attribution.

The Challenges Facing These ID Solutions

Apart from the fact that some of the solutions don’t scale in the same way as they once did (i.e. IDs created from hashed email addresses aren’t as readily available as IDs stored in third-party cookies), all these identity solutions face the same challenges — they still revolve around identification and rely on some type of ID. The reason this is a problem is because walled gardens like Google and Apple are constantly strengthening their products to make them more privacy friendly.

We’ve seen this with Apple’s ITP and changes to IDFA, and even Google has made changes to how Chrome handles third-party cookies and is also planning on phasing them out in the second half of 2024.

AdTech companies are moving from one identification method to another, and it won’t be long until Apple and/or Google make some changes to their web browsers or mobile operating systems to prevent these identification methods.

For this reason, many folks in the industry believe that these ID solutions are rather short-term solutions. Many say that the future of digital advertising and marketing won’t be done on an individual basis, but rather done in a privacy friendly way where individuals are not identified.

It’s too early to say if and when identification will disappear completely, so in the meantime, companies need to use an identity solution like the ones listed above to ensure they can still run effective advertising and marketing campaigns.

The Future of User Identification in Web Browsers and Mobile Apps

The end of third-party cookies in web browsers means that companies will need to change the way they identify users to continue powering key AdTech processes, such as behavioral targeting and measurement.

Several possible solutions have been proposed, including using email addresses as an ID and utilizing local storage, but many are limited to one domain and therefore won’t be useful for cross-site identification.

At the moment, there’s no clear alternative to third-party cookies or standards that can be applied by all companies in the digital advertising ecosystem. But initiatives like the IAB’s Rearc Project, which released its first addressability specification called Seller Defined Audiences in February 2022, will help bridge this gap.

Similarly, the future of mobile identifiers also looks bleak with many folks in programmatic advertising suggesting that it’s only a matter of time before Google and Apple turn off their mobile IDs.

Chapter Summary

- Identifying users is needed to power ad targeting, content personlization, measurement, conversion tracking, attribution, and frequency capping.

- There are different ways to identify users depending on the environment, such as whether the user is using a web browser or a mobile app.

- Web browsers use cookies, device fingerprints, and local storage to identify users.

- Mobile apps use devices IDs to identify users.

- Deterministic and probabilistic matching are processes used to identify users across different devices.

- There are a number of challenges to identifying users, such as privacy laws like the GDPR and technical limitations like web browser settings and ad blockers.

Test your knowledge with our quiz!

Download the PDF version of our AdTech Book

Read and download the PDF and register your interest for the hardcover version.

Download the PDF version of our AdTech Book

Fill in the form to download the PDF and join our AdTech Book email list to receive all future updated versions, including information about the release of the hardcover version.