Although the advancement of technology and growth of digital advertising has helped publishers increase revenue and allowed advertisers to reach more of their audience, it has also given rise to some very costly problems for all companies involved in digital advertising.

Two such problems are ad fraud and issues around ad viewability.

Ad Fraud

Ad fraud in digital advertising is a multi-billion dollar problem. There are many types of ad fraud, but they all work by misrepresenting advertising metrics, such as impressions, clicks, and conversions for monetary gain.

The Cost of Ad Fraud

Numerous studies show that ad fraud costs the digital advertising industry between US $26 billion and US $42 billion a year. To put that into perspective, global digital ad spend in 2019 was estimated to be US $333.25 billion.

Below are some figures from recent studies into the cost of ad fraud.

$26 billion: CHEQ, an ad fraud solution, found that ad fraud could cost the online advertising industry US $26 billion in 2020.

$42 billion to $100 billion: Juniper Research estimates that ad fraud cost advertisers US $42 billion in 2019, with this number rising to US $100 billion by 2023.

10% to 30%: The World Federation of Advertisers estimates that 10% to 30% of advertising is not seen by consumers because of ad fraud and problems with ad viewability.

Determining the true cost and scale of ad fraud is difficult because:

- It can be very hard to detect fraudulent activity due to the sophistication of the ad fraud techniques.

- The technology to protect advertisers is constantly stuck in a game of cat and mouse with fraudsters.

- Most ad fraud goes undetected and many companies choose not to publicly disclose the fact that they’ve been impacted by it.

All these factors mean that the actual impact of ad fraud may be higher than what is reported.

There are a number of reasons why this figure is so huge:

- Fraudsters follow the money. Ad fraud moves from one lucrative area to another. The increase in ad spend has attracted more fraudulent behavior. You’ll often see an increase in ad fraud in emerging areas of digital advertising, such as mobile in-app and OTT/CTV (more on this below).

- Digital advertising is less regulated than the financial industries, meaning it’s easier for fraudsters to get away with their criminal activities.

- The digital advertising ecosystem is fragmented and complex, which makes it easier for fraudsters to conceal their activity.

The Main Types of Ad Fraud

What makes online ad fraud so challenging is that there are several ways to steal money from advertisers and publishers, with new ad fraud methods being created all the time.

The most common ad fraud techniques include:

Invisible and Hidden Ads

With this ad fraud technique, ads will be invisible or hidden on websites, but an impression will still be recorded.

There a few ways fraudsters can carry out this technique:

- Display an ad in a 1×1 pixel iframe.

- Display ads outside of the viewport area.

- Display (multiple) re-sized ads.

- Display several ads in an iframe loaded to a single ad slot so that out of all the ads loaded, only one will actually be visible to the user. This is also known as ad stacking.

This technique is not the same as non-viewable impressions (see below) whereby ads are displayed on a website and recorded but aren’t seen by a user because they’re at the bottom of the page where the user doesn’t scroll to.

Domain Spoofing

Domain spoofing involves a fraudulent website disguising itself as a genuine and often premium website. Some fraudulent AdTech platforms can also carry out domain spoofing.

Brands pay high CPMs to display their ads on premium websites or websites where their target audience is, so by disguising itself as one of these websites, fraudsters can take the ad revenue that should have gone to the real website.

Ad Injection

Also known as hijacked ads, this type of ad fraud injects ads into unsuspecting websites, usually via malicious browser plugins or mobile apps.

Ad injection can be done in a few ways:

- Compromising the user’s computer to change the DNS resolver — e.g. by resolving the ad.doubleclick.com domain to the IP of the server controlled by the attacker and therefore serving different ads.

- Compromising the publisher’s website or the user’s computer to change the HTML content on the fly — e.g. changing ad tags placed by the publisher to tags controlled by the attacker.

- Compromising the user’s proxy server or router (or the ISP’s router) to spoof the DNS server or change the HTML content of the site on the fly.

Click Injection

Click injection, also known as hijacked clicks, is a similar technique to ad injection, but instead of injecting ads into a web page, fraudsters will inject clicks. The way fraudsters make money is by receiving money for the click and also the conversion.

So instead of the commission for a conversion going to a genuine publisher or mobile app, it would go to the fraudster as their fake click would be recorded as the last touch before the conversion.

Cookie Stuffing

The cookie-stuffing technique is used to steal money from CPA or affiliate marketing campaigns.

Because cookies are often used to attribute conversions, fraudsters will stuff a user’s browser with cookies they’ve either created themselves or have stolen from other publishers. This allows them to receive commissions from affiliate networks when a user completes a conversion on a publisher’s websites (e.g. purchases a product).

How Ad Fraud Is Carried Out

The above types of ad fraud can be carried out in many ways:

Bot traffic: Non-human traffic generated by botnets, which consist of compromised computers, cloud servers, and proxy servers. This type of traffic is often referred to as sophisticated invalid traffic (SIVT).

Click farms and device farms: A collection of devices (laptops and mobile phones) used to generate fraudulent impressions, clicks, and conversions (e.g. app installs). These farms are sometimes operated by humans or via programs installed on the devices.

Methbot and 3ve

Although there are many botnets and types of malware, the most costly botnets ever discovered are Methbot and 3ve.

These botnets were elaborate and sophisticated operations that stole an estimated US $36 million from advertisers between 2014 and 2018.

Ad fraud is rarely investigated by law enforcement, but in November 2018 the US Department of Justice (DoJ) issued a release saying it has indicted 8 people over the Methbot and 3ve schemes.

The investigation is the largest criminal investigation into ad fraud that has ever taken place and involved the FBI, the US Department of Homeland Security, and private companies including Google and White Ops.

Ad Fraud in Emerging Areas of Digital Advertising

Although ad fraud began in the display advertising world, it has moved into other emerging areas of digital advertising such as mobile in-app and OTT/CTV.

Mobile In-App Ad Fraud

Many of the ad fraud techniques used in web browsers are also found in mobile in-app environments. But there are a few that are specific to mobile in-app.

App or SDK spoofing: Similar to domain spoofing, this technique tricks advertisers into thinking that their ad will appear in a premium app, when it will actually appear in a fraudulent app.

Ad stacking: Ads are placed on top of one another so the app earns more ad revenue, but only one ad is displayed to the user.

Click injection: Just like click injection in web browsers, fraudsters collect ad revenue and affiliate commissions for clicks they didn’t generate themselves.

Hidden ads: Fraudsters run ads in the background of apps, giving off the impression that they are being displayed to users when they aren’t.

Malware: Malicious apps that carry out one or more of the above techniques to generate fraudulent ad revenue.

OTT & CTV

The over-the-top (OTT) and connected TV (CTV) industries are ripe for ad fraud; they are emerging and growing areas of digital advertising with higher CPMs than other channels, there’s no direct connection between buyers and sellers, there’s a lack of transparency, and brands are pouring more money into them.

Pixalate, an ad fraud intelligence and marketing compliance company, recently uncovered two ad fraud schemes in the OTT/CTV environment. Pixalate has named these schemes DiCaprio and Monarch.

The DiCaprio ad fraud scheme used similar techniques found in web browsers and mobile apps to fool advertisers into thinking that they were bidding on inventory on Roku devices.

It seems that fraudsters compromised the security of the popular social networking app Grindr to send out ad requests via a script, which contained the name DiCaprio.

The ad requests appeared to come from Roku apps on Roku devices. Advertisers would bid on these ad requests believing their ads would be shown to Roku users, when in fact they would run in the background inside the Grindr app.

The Monarch scheme used a spoofing technique to make it appear that ads would be displayed on premium Roku apps, when actually they would end up on non-premium apps like screensavers. Unlike the DiCaprio scheme that involved mobile devices, the Monarch scheme was contained to Roku apps and devices.

In another ad-fraud scheme, known as Icebucket, detected by bot-mitigation company White Ops, fraudsters impersonated more than 2 million people and generated 1.9 billion ad requests on OTT/CTV and mobile devices.

The scheme used a botnet to produce artificial viewing activity on edge devices (mainly mobile and CTV devices).

How Advertisers And Publishers Can Defend Against Ad Fraud

Combating ad fraud is an ongoing battle, but there are a couple of things publishers, brands, agencies, and AdTech companies can do to reduce ad fraud.

1. Use Ad Fraud Detection Software

There are several software companies that detect and prevent many of the ad fraud techniques listed above for different advertising channels. Many AdTech companies also provide ad-fraud detection features as part of their offering.

Below are some of the main cybersecurity and ad-fraud detection companies:

2. Adopt IAB standards

Over the past few years, the IAB has produced a number of standards to help reduce ad fraud in web browsers and mobile apps. These include ads.txt, app-ads.txt, and sellers.json.

Authorized digital sellers (ads.txt)

Ads.txt aims to tackle domain spoofing (a type of ad fraud) and arbitrage, which is a process where impressions are bought and then repackaged and resold at a higher price by a third party. Ads.txt helps to solve this problem by indicating who the authorized sellers and resellers of a publisher’s inventory are.

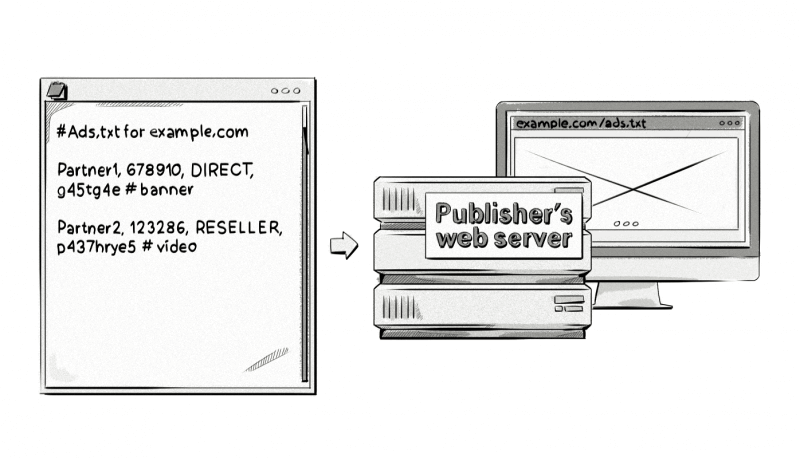

To adopt the standard, a publisher adds an ads.txt file containing information about all the programmatic partners (supply-side platforms, ad exchanges, ad networks, etc.) they work with to their web server and host it under their root domain.

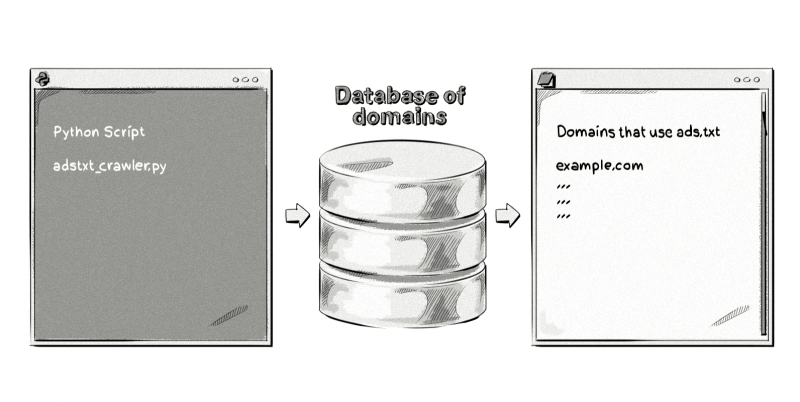

Advertisers or AdTech companies can then use a script to crawl the web (or a database of domains) to collect the ads.txt files from publishers.

Advertisers can then reference a publisher’s ads.txt file against IDs in OpenRTB bid requests. If there’s a match, then advertisers can be assured that they are buying inventory from genuine publishers.

You can see whether a publisher has an ads.txt file and view the contents of it by adding /ads.txt to the end of a root domain, e.g. businessinsider.com/ads.txtand cnn.com/ads.txt.

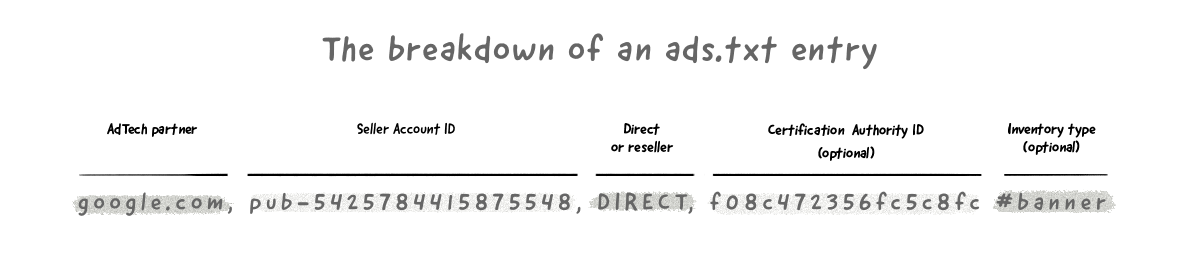

Here’s a breakdown of the information in the above ads.txt entry:

AdTech partner – The AdTech platform, typically supply-side platforms and ad exchanges, the publisher uses to sell their inventory. Examples include google.com, appnexus.com, bidfluence.com, rubiconproject.com and pubmatic.com.

Seller Account ID – This represents the publisher’s account ID for the respective AdTech vendors and is used to verify the authenticity of the inventory during RTB auctions.

Direct or reseller – Direct means that the publisher works directly with the AdTech vendor to sell its inventory. Reseller means that the publisher has authorized another company to sell its inventory on its behalf. For example, SSP2 (reseller) could sell the publisher’s inventory via SSP1 (direct).

Certification Authority ID – This optional field represents the advertising system within a certification authority, for example, the Trustworthy Accountability Group (TAG).

Inventory type – Some publishers include this optional field so they know which type of inventory the AdTech vendor sells (view cnn.com/ads.txt to see examples). As this hashtag represents a comment, it won’t be picked up by the crawling script unless certain configurations are made to it, but as this is purely for the publisher’s benefit, there’s no real need for buyers to have this information.

Authorized digital sellers for apps (app-ads.txt)

App-ads.txt is the mobile app version of ads.txt, but with a few differences in the setup.

To adopt app-ads.txt, app developers need to provide a developer website URL in app store listings and publish an app-ads.text file. App stores are also encouraged to publish three HTML <meta> tags with the store listing page for each individual app to allow advertisers and AdTech companies to match the bundle_id and/or store_id in bid requests.

Here’s an example of the three HTML meta tags provided by the IAB:

<meta name="appstore:developer_url" content="https://www.path.to/page" />

<meta name="appstore:bundle_id" content="com.example.myapp" />

<meta name="appstore:store_id" content="SKU12345" />

Advertisers and AdTech companies then need to crawl app listing pages in app stores to retrieve these three HTML meta tags, translate the developer URL to an app-ads.txt path, and then crawl the web for the app-ads.txt file and interpret them.

Ads.cert

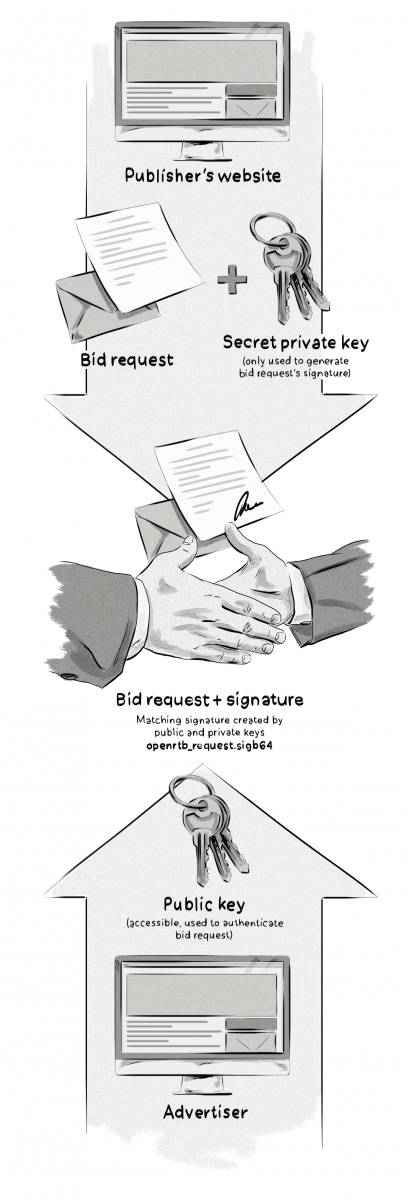

Ads.cert is considered a more secure version of ads.txt and aims to increase transparency into programmatic ad buying by providing cryptographically signed bid requests. By doing so, media buyers can be sure that the information being sent in the bid request (e.g. the publisher’s URL, user’s location, user’s IP, and user’s device) is factual.

Here’s how the process works, step by step:

- OpenSSL’s security software is used by the publisher to generate a pair of ECDSA keys based on the bid request:

- Public (secured, yet accessible, to be read by systems which validate the bid request against the signatures). The Public Key file must be shared via HTTP and/or HTTPS from the publisher’s website under a relative path on the server: /ads.cert. Although ads.cert is referred to as a file, the resource does not need to come from a file system.

- Private (secret, secure, and inaccessible to outside systems, yet accessible to the systems that generate and sign bid requests, e.g. SSP). Private keys are in a standard format known to compatible security packages.

- An encrypted signature based on the bid request is generated with a private key and attached to the bid request and sent out on behalf of the publisher by an SSP, with details about the impression available, publisher’s website or app, industry, language, etc.

- The recipient of the request will then use the public key to generate another signature for that same bid request.

- The signatures generated by the publisher and by the recipient are compared to check if they were generated based on the same bid request (created using a matching pair of keys). If yes, then the bid request is considered legit. Any alterations of the signed elements can be detected by the recipient or other servers in the chain.

The main drawback of ads.cert is that it’s only available with OpenRTB 3.0, which is not currently supported by a majority of AdTech platforms.

Sellers.json and the OpenRTB Supply Chain Object

Sellers.json allows media buyers to see all the sellers and resellers involved in a bid request. In many ways, sellers.json is an extension to ads.txt. So instead of just seeing a list of authorized sellers and resellers in an ads.txt file, sellers.json lists the final seller of a bid request.

The OpenRTB Supply Chain Object is part of sellers.json and provides a record of all the sellers (direct) and resellers that have been involved in bid requests.

By viewing all of the entities (referred to as nodes) involved in bid requests, media buyers can get more transparency into the supply chain, identify whether the entities are partners they want to work with, and see how many entities the bid passed through before it was delivered to publishers.

Ad Viewability

Ad viewability refers to whether an ad was seen by a human or not.

Although non-viewable ads can be a result of ad fraud, such as if a publisher uses bots to generate impressions, in most cases the reason is not sinister, for example if an ad is located at the bottom of a page where a user doesn’t scroll to.

Ad viewability is one of the biggest issues in today’s online advertising world with some sources stating that over half of all ads served are not actually viewed by an online user.

A large majority of AdTech platforms do a pretty good job of determining whether an ad has been served and whether an ad has been clicked on, but determining whether an ad was actually viewed by a user can be hard to measure.

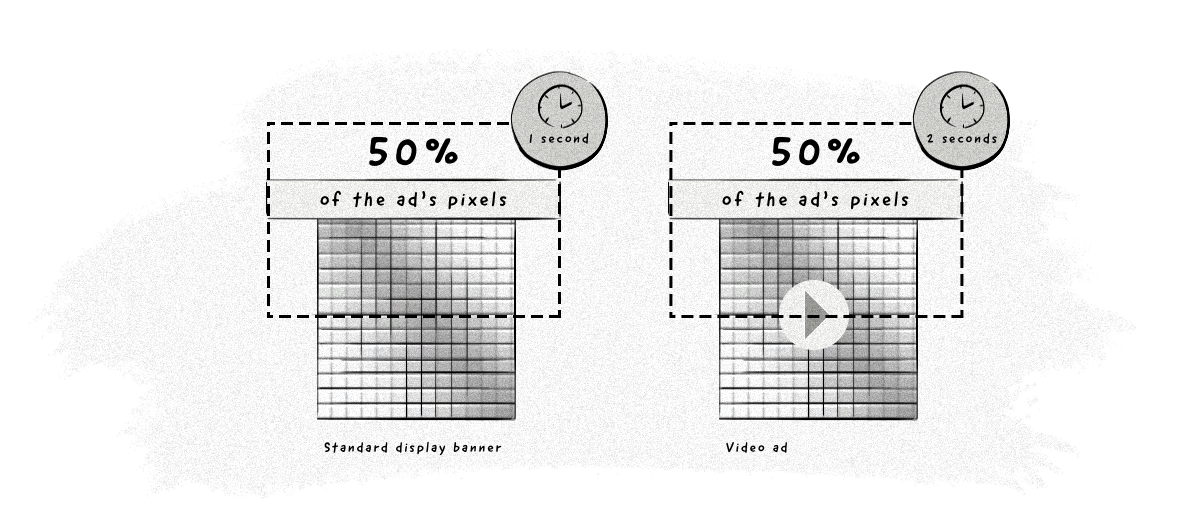

The current industry standard provided by IAB and the Media Rating Council (MRC) states that for an ad to be registered as viewed, it needs to have met these two criteria:

For display ads: 50% of the ad’s pixel needs to be in the web browser’s viewport for a minimum of 1 second.

For video ads: 50% of the ad’s pixel needs to be in the web browser’s viewport for a minimum of 2 seconds.

Viewable Impressions

As we saw in the ad server chapter, impression trackers are used by both advertisers and publishers to track the number of impressions an ad receives.

However, this only tracks impressions that are served; it doesn’t tell us if the ad was actually viewed by a user. So not only do you need to track the number of impressions served, you also need to determine if the impression was actually seen by a real user.

Ads may be served but not viewed because of one or more of the following reasons:

- The ad may have taken too long to load, leaving a blank space where the ad should have been.

- The user could have scrolled down or switched tabs or windows before an ad could be displayed to them.

- The user could be using an ad-blocking plugin like AdBlockPlus, uBlock, or Ghostery.

- There might have been some technical issues with the webpage or web browser.

Also, there are a number of fraudulent long-tail sites that perform all kinds of tricks to record an ad impression, when in fact, the ads could never be seen on the page at all.

What is a long-tail website?

A long-tail website refers to a small publisher or individual blogger.

Typically, these sites will monetize their site with Google AdSense and the inventory on these sites is known as long-tail inventory.

A lot of hope is placed in the so-called viewable impression.

The idea behind viewable impression is pretty straightforward:

An advertiser pays only for ad impressions that were actually seen by a user.

Sounds simple, but the problem is much more complex when analyzed from the technical perspective.

Luckily, companies like Google, DoubleVerify, IAS, and Moat offer ad viewability measurement software to help advertisers determine how many of their ads were actually viewed by users.

Chapter Summary

- Ad fraud costs the digital advertising industry between US $26 billion and US $42 billion a year.

- The most common types of ad fraud in web browsers are:

- Invisible and hidden ads.

- Domain spoofing.

- Ad injection.

- Click injection.

- Cookie stuffing.

- Ad fraud is also a problem with mobile in-app advertising and is emerging in growing areas of digital advertising like OTT/CTV.

- Companies can detect and reduce ad fraud by using ad fraud detection software and adopting IAB standards like ads.txt, app-ads.txt, ads.cert, and sellers.json.

- Ad viewability refers to whether an ad was seen by a human or not.

- Ad viewability is one of the biggest issues in today’s online advertising world with some sources stating that over half of all ads served are not actually viewed by an online user.

- IAB and the Media Rating Council (MRC) states that for an ad to be registered as viewed, it needs to have met these two criteria:

- Display ads: 50% of the ad’s pixel needs to be in the browser’s viewport and seen for a minimum of 1 second.

- Video ads: 50% of the video needs to be visible and seen for a minimum of 2 seconds.

- Viewable impressions refers to ad impressions that meet the criteria above and are actually seen by a user.

Test your knowledge with our quiz!

Download the PDF version of our AdTech Book

Read and download the PDF and register your interest for the hardcover version.

Download the PDF version of our AdTech Book

Fill in the form to download the PDF and join our AdTech Book email list to receive all future updated versions, including information about the release of the hardcover version.